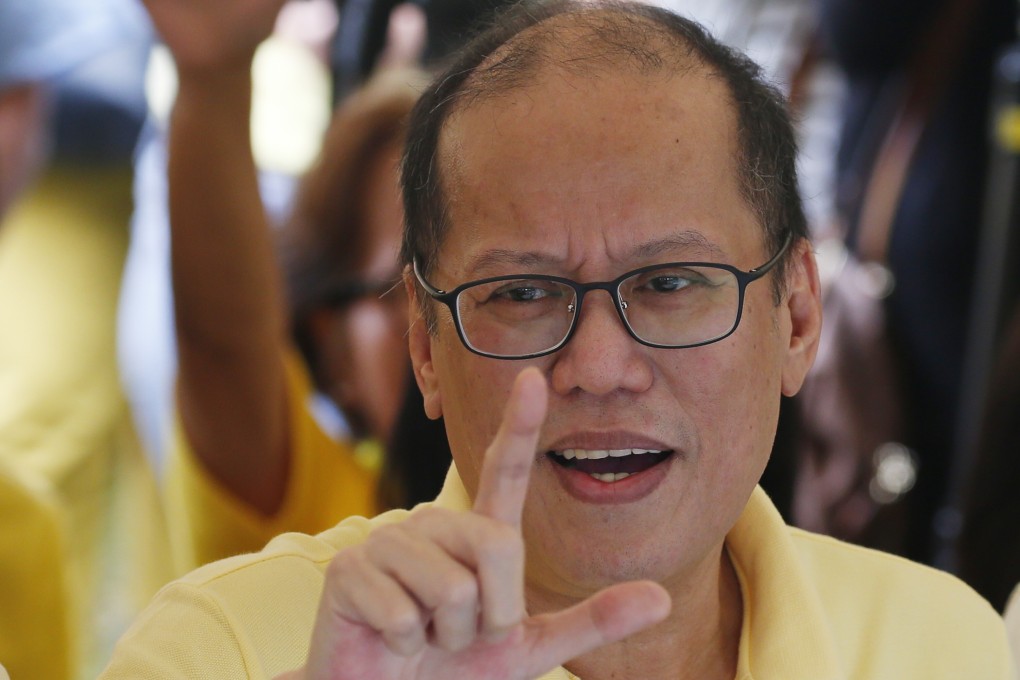

Opinion | Benigno Aquino’s lost liberal ‘yellow’ legacy in the Philippines

- The late former president’s liberal reformist agenda was upended by his failure to address structural problems, which successor Rodrigo Duterte seized upon

- But his legacy of decency, commitment to democracy and national sovereignty may one day again prove relevant in a post-populist Philippines

This popular music-inspired symbol (“Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree”) refers to the welcome planned by supporters for his father, Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jnr, the leading opponent of the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos who was assassinated at the Manila International Airport after attempting to return from exile in 1983.

But even this limited sympathy is in stark contrast to the huge anti-government protests following his father’s killing and the national grieving after his mother, former president Corazon “Cory” C. Aquino, died in 2009, setting up Noynoy Aquino’s successful presidential campaign a year later.

But it should also be remembered that Noynoy Aquino easily won the presidency in 2010 by promising to take a “straight path” and clean up corruption – a popular message coming on the heels of the scandal-plagued administration of previous president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.