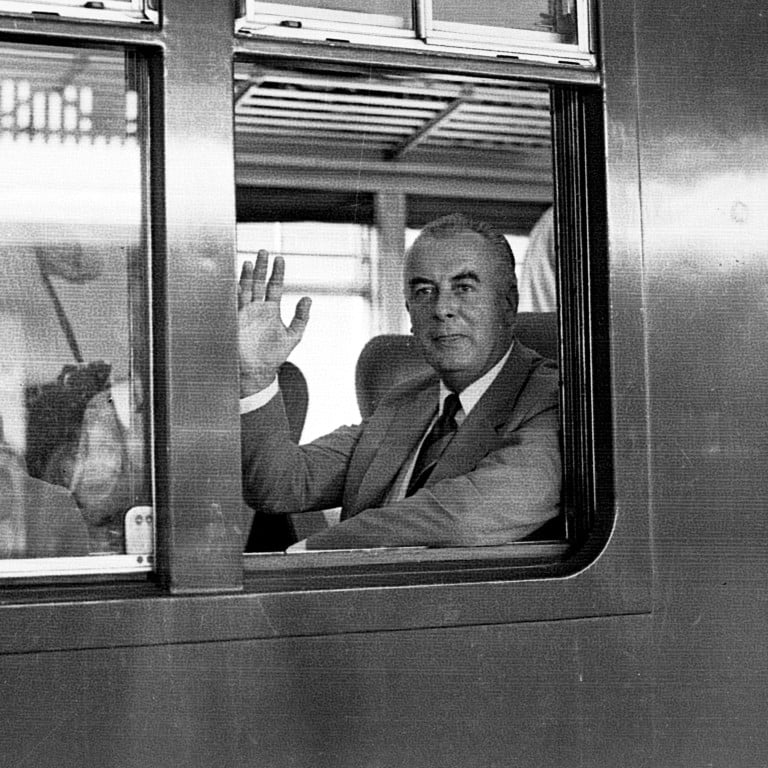

China-Australia relations: what Canberra can learn from Gough Whitlam and its own diplomatic history

- Gough Whitlam’s landmark 1971 China visit offers lessons in statecraft: a quality absent from much modern-day Australian diplomacy, writes Tony Walker

- His trip ushered in more than four decades of relatively harmonious relations between Canberra and Beijing – until the recent diplomatic cul-de-sac

Historical anniversaries sometimes – not always – provide an opportunity to take stock. Rarely do two anniversaries coincide that encourage such an opportunity.

The two anniversaries, within a few days of each other, should remind us of both the costs and benefits of a complex relationship, and indeed the challenges and threats.

1921 tops Chinese box office, but is it anything more than Communist propaganda?

Xi’s speech was effectively a call to arms by a Chinese leader who has emerged as his country’s new emperor.

In that regard, Xi is a successor to Mao Zedong and not Deng Xiaoping, who exercised power mostly behind the scenes.

Xi might have dressed himself in a colour-coded grey Mao suit identical to that worn by Mao when he proclaimed the People’s Republic on October 1, 1949, but there is not much that is grey about his ambitions for his country.

In one of more pointed sentences in an hour-long speech, he said: “The Chinese people are not only good at destroying an old world, but also good at building a new world.”

04:14

Xi Jinping leads celebrations marking centenary of China’s ruling Communist Party

All this brings us back to the anniversary of Whitlam’s outreach to China in 1971. Documents associated with that historic visit, usefully published by The Australian, remind us that in an earlier era Australia was well-served by a politician capable of navigating potentially treacherous diplomatic terrain.

At the time, the opposition leader, still 18 months away from becoming prime minister, went to Beijing to distinguish Labor from a stale Coalition facsimile of US policy.

Mainland Chinese magazine outlines how surprise attack on Taiwan could occur

Whitlam’s own dispatches, published by The Australian, and independent accounts of his exchanges with Premier Zhou Enlai, revealed he more than held his own with China’s master diplomat. These included, principally, the question of Taiwan in what became the blueprint for Australia’s “one-China policy”.

This stated that “Australia adheres to a one-China policy which means we do not recognise Taiwan as a country, but we maintain economic and cultural ties”. This conforms more or less with the US formula published in the Shanghai Communique of February 1972, signed by President Richard Nixon and Zhou.

Whitlam was lucky politically in the sense that no sooner had then-Prime Minister William McMahon berated him for allowing himself to be “played as a fisherman plays a trout” by Zhou, it emerged that even as the opposition leader was in Beijing, US National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger was in the Chinese capital arranging a visit by Nixon.

Whitlam’s timing could hardly have been more advantageous to him politically, and more propitious from an Australian point of view. The newly-elected Whitlam government recognised the one-China principle as one of its first acts after being elected in December 1972.

It is a different China [now] but that does not absolve us of the responsibility of trying to engage with it

This was followed by more than four decades of relatively harmonious relations between Canberra and Beijing, upset on occasions by episodes like the Tiananmen massacre. That was until China began to assert itself more aggressively in its own neighbourhood, and ours.

On the 50th anniversary of Whitlam’s groundbreaking mission to Beijing, it is reasonable to ask how he would have managed relations with a more assertive China in this latest period.

Since Whitlam is no longer with us, the words of Australia’s first ambassador to China and Whitlam’s interpreter on his 1971 China mission might be useful.

In the view of Stephen FitzGerald, Australia needs to find a way to make use of both formal diplomatic channels, and, if necessary, and maybe preferably, “backchannels”. This is the realpolitik argument that tends to be ignored in Canberra these days, where China policy is dominated by the national security establishment.

“It is a different China but that does not absolve us of the responsibility of trying to engage with it. It does not matter what you think about the government and, let’s face it, the government in China when Whitlam went in 1971 was not exactly a lovable government. China is now economically bigger, more powerful, but you have to engage with a country like whatever you think of it. This is what Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Vietnam are doing,” he said.

“You don’t have to become like them, neither can you hope to make them become like you … There will be rough spots and you have to deal with that. But deal with them as issues in a partnership which you want to keep going and not issues, which add up to an adversary which you are trying to suppress.”

On the anniversary of the Whitlam breakthrough these sentiments may be all very well, but the reasonable question is what the choice is.

Is China a ‘market economy’, and does it matter in WTO dispute with Australia?

Morrison and his foreign policy team should pay particular attention to Whitlam’s emphasis in his conversations with Zhou, and in his written accounts of his visit to China, on Australia’s own significance as a middle power seeking to play a constructive role in the region.

This was Whitlam’s way of conveying to the Chinese that Canberra, under his leadership, would seek to define itself and its own interests from those of its American ally. That is, not in contradiction to Washington necessarily, but from Australia’s own middle-power standpoint.

Morrison and his advisers might pay heed to these lessons if he is to get Australia out of the diplomatic cul-de-sac with China in which it finds itself.

A bit of creative statecraft, along the lines suggested by FitzGerald, would not go astray.

Read the original article at The Conversation