Advertisement

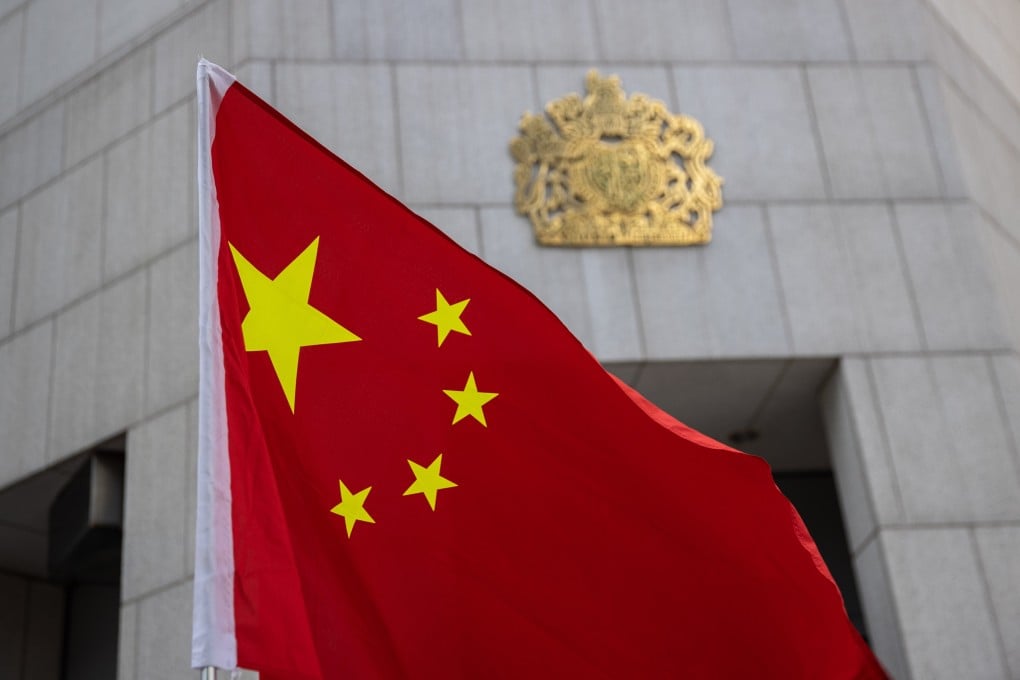

On Reflection | If China weaponises capital, it will shoot itself in the foot

- British opposition to a takeover of the Welsh microchip factory Newport Wafer Fab by the Chinese-backed company Nexperia shows need for consistent, long-term strategy

- If Britain blocks off all Chinese deals on the grounds of national security its economy will take a hit; if China responds in anger it will damage its own long-term interests

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

19

The word maodun, or contradiction, has a long history in Chinese Marxist thought, but its origins go back long before communism. It refers to the “contradiction” between a spear that penetrates anything, and a shield that can never be pierced: irresistible force meets immovable object.

I was reminded of that fable last week during the attempted purchase of a failing chip factory (computer, not potato) in Wales by a Chinese-backed company, Nexperia.

The British government initially refused to intervene, but a political outcry led to Prime Minister Boris Johnson ordering a review under Britain’s still-new National Security and Investment Act.

Advertisement

Opponents of the deal argue that Britain should not be selling a company that makes semiconductors, one of the most valuable commodities in the world right now, to a Beijing-backed firm.

Supporters of the deal point out that the factory – Newport Wafer Fab – does not make the most sophisticated type of chips and that the factory is only being taken over because none of its previous owners could get it to make money.

Advertisement

Whatever happens to the factory, there is a bigger question that is still in flux. Britain is typical of most Western countries in that it is becoming increasing concerned about the security implications of any deals with China.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x