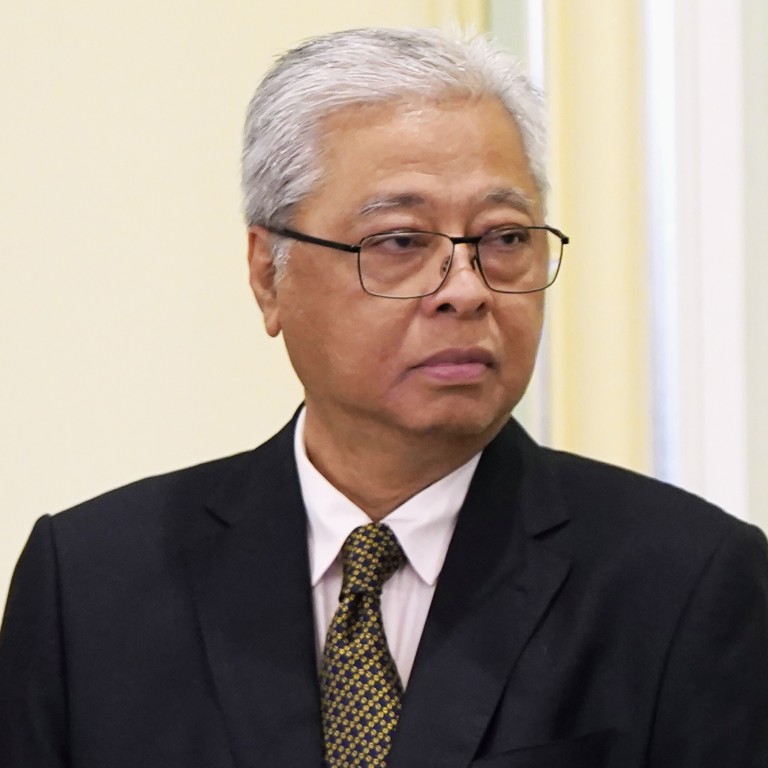

Can Malaysia’s new prime minister end political instability?

- Ismail Sabri Yaakob looks set to succeed Muhyiddin Yassin, but he has a slim majority and was part of the government criticised over its pandemic response

- The Covid-19 vaccination rate may help him, but he faces the challenges of intra-Malay competition and broadening the political base of policymaking

For months, Muhyiddin has been the face of Malaysia’s failure to control the pandemic, and many netizens and young protesters believe that his resignation is a necessary condition for such a turnaround. However, Ismail Sabri, formerly the senior minister coordinating the lockdown measures that were slammed for being ill-planned and flip-flopping, was also part of the failure, instead of a hope.

Even an Umno MP Azalina Saad publicly predicted that the government may only last for six months, much shorter than Muhyiddin’s 17 months in office and his predecessor Mahathir Mohamad’s 22 months.

Malaysia’s powerful king and deputy king – rotating five-year terms by nine sultans – have called for an end to the “winner-takes-all” politics which has continued for seven decades since the nation’s independence from Britain.

Two solutions have been widely discussed by political actors. The first is a unity government, like a wartime cabinet, inclusive of all parties and with limited mandates on only health and the economy. The second is a Confidence and Supply Agreement (CSA) between the government and opposition that protects government lifespans in exchange for reforms and a level playing field for the opposition.

Three days before his resignation, Muhyiddin made a last-minute appeal to the opposition on national TV with a CSA offering seven institutional reforms in exchange for his survival till next July. The opposition parties and their supporters staunchly dismissed his offer as insincere and untrustworthy and demanded his resignation.

A second liner before his promotion as senior minister by Muhyiddin 17 months ago, Ismail Sabri is certainly much weaker than Muhyiddin in steering the National Alliance (PN) government.

Created to replace the Mahathir-led reformist Alliance of Hope (PH) government last March, the fragile coalition consists mainly of three Malay-Muslim nationalist parties: Umno, in which Ismail is a vice-president, Muhyiddin’s Bersatu, which is a splinter of Umno produced by the fallout of the 1MDB scandal, and the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS). There are also a regional bloc in Sarawak, GPS, and some minor parties.

Except for PAS, the long-time Islamist opposition, PN is effectively the regrouping of the National Front (BN) coalition which dominated Malaysia for 61 years from independence until its electoral defeat in 2018.

However, unlike BN with Umno as the hegemonic core, PN is rife with Umno and Bersatu’s bitter rivalry for dominance of the Malay-Muslim nationalist vote bank, both further divided into factions, and the smaller PAS placing its bets on different players.

Ismail Sabri’s premiership will have a positive factor and two colossal structural challenges.

The positive aspect is that the fast vaccination rate may arrest the rise of new coronavirus cases and deaths, allowing the economy to reopen gradually as Malaysia approaches herd immunity. Under the leadership of the able minister Khairy Jamaluddin, the only star in Muhyiddin’s cabinet, Malaysia has administered over 28 million vaccine doses and 48 per cent of the population is fully vaccinated.

This has led many in Umno and PN to seek a fresh election in months, hoping to capitalise on the public’s fatigue of the political stalemate.

However, as Malaysia’s third wave was caused by an untimely state election in Sabah last September, the public is unlikely to welcome an election before economic activities return to normal.

With the emergence of more aggressive variants globally, booster doses may be necessary and herd immunity may be called into question any time.

Ismail Sabri’s first structural challenge is intra-Malay competition. Contrary to the fear of many minorities and liberals, the biggest victim of PN’s Malay-Muslim unity government is not the ethnic minorities, but ironically the cause of Malay-Muslim unity itself.

Malay-Muslim nationalists have long framed non-Malays as the ethnic majority Malay-Muslims’ biggest existential threat, with the only solution being Malay parties merging into one or joining forces.

However, like three brothers competing for the same love interest, Umno, Bersatu and PAS – itself an old Umno splinter born in 1951 – cannot be united despite similar ideologies.

More fundamentally, their rivalry has not resulted in policy differentiation and competition to benefit the public. While Umno hammered PN as a failed government for the past year before withdrawing its support and causing Muhyiddin’s downfall, it has offered no alternative programme and its MPs made up a quarter of Muhyiddin’s ministers and deputy ministers.

Despite the latest make-up, Umno wants to eliminate Bersatu in the next election and the tension between the two parties will continue unless a merger is negotiated. However, if Bersatu can be eliminated or absorbed by Umno, PAS – which had been Umno’s arch enemy for decades – would lose sleep.

At a personal level, Ismail Sabri will face a dilemma in picking his cabinet members, even if the rival parties and warlords that enthrone him are willing to give him some autonomy. Promoting competent leaders like Khairy or Razaleigh to senior positions would boost his cabinet’s credibility but that may also prepare them or others for a quick takeover after an election. On the other hand, a cabinet built on considerations for survival instead of merit may intensify public rejection and bury his government in the next election or others.

The second structural challenge is broadening the political base of policymaking. Malaysia’s political system since the aftermath of the 1969 ethnic riots has effectively been an oligarchy of ministers and top bureaucrats, notwithstanding periodical elections.

Parliament’s role is fundamentally an electoral college to formally install the prime minister and approve all his laws, budgets and policies. Opposition parliamentarians and even government backbenchers are not trusted as intelligent and responsible enough for real consultation in legislation and policymaking. Parliamentary debates are only theatrical shows for the next elections with little impact on bills, policies and budgets.

Power is also concentrated vertically as Malaysian state governments have very limited power so that they cannot deviate from the centre’s planning. Health, education, transport, local policing and other matters normally reserved for state governments in federations are all centrally controlled in Malaysia.

The high concentration of power with a narrow political base of winners has become obviously detrimental during the Covid-19 pandemic. On one hand, it produces policy blind spots and invites public backlash followed by flip-flops. On the other hand, political responsibility is solely born by the government, creating difficulty in making necessary but unpopular decisions.

Ismail Sabri’s best option may be picking up his predecessor’s CSA offer for a cross-party peace deal with the opposition. Continuing majoritarianism on a 51.8 per cent majority or a unity government with more uncontrollable undercurrents seems to be a recipe for a quick and/or disastrous end for his job.