Who is winning the US-China battle for the hearts and minds of Vietnam’s cybersphere?

- Beijing’s actions in the South China Sea and Mekong River have exacerbated anti-China sentiment in Vietnam, pushing it closer to the US

- Analysis of their embassy Facebook posts by Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute found China has a long way to go in making its image more ‘lovable’

The cartoon shows a man about to drown at sea, crying out for help. Another person standing ashore throws a lifebuoy to the man in need, urging: “Grab the S lifebuoy.” But the drowning man shouts back: “I only need the M lifebuoy.” The would-be rescuer makes the final call by letting the crying man drift away, bidding him farewell: “Goodbye, brother!”

The cartoon was removed by Sunday morning.

Harris will on Tuesday travel to Vietnam, where the message that “America is back” has never resonated more strongly.

The “State of Southeast Asia 2021” survey, published in February by Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, found that of the 1,032 people polled in 10 Southeast Asian countries – including academics, government officials and businesspeople – Vietnamese are most wary of China’s growing strategic clout and most supportive of US influence in the region.

Against that backdrop, the US-China battle for hearts and minds in the Vietnamese cybersphere has laid bare two different public responses.

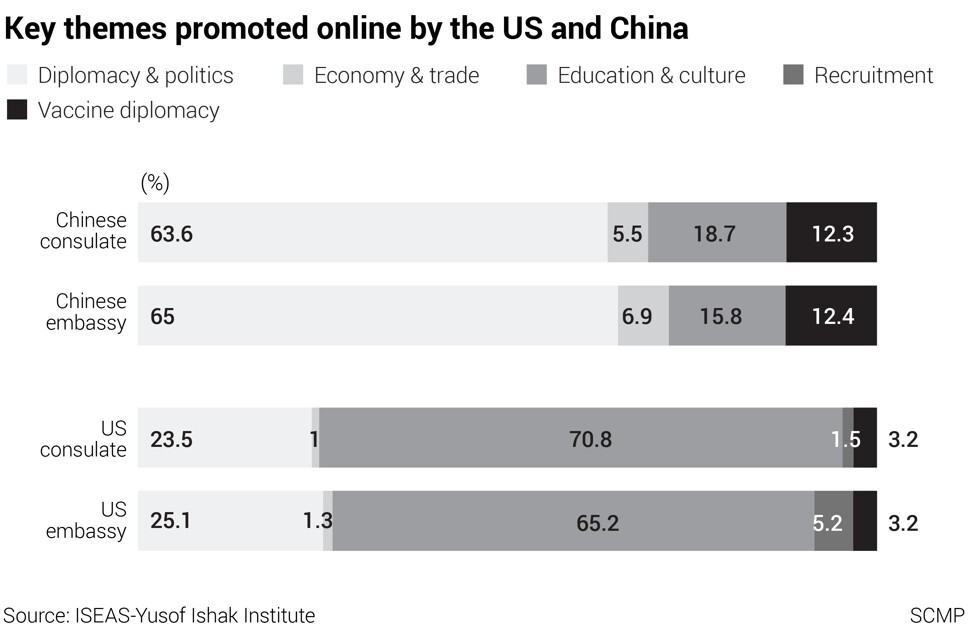

The Media, Technology and Society Programme at the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute set out to examine the issues and messages telegraphed by the US and China to Vietnamese audiences online. An analysis of all Facebook posts by both diplomatic missions between January and July offers several intriguing takeaways.

A key tenet of China’s public diplomacy efforts in Vietnam has been to ramp up condemnation of the US agenda. Sticking to the party line dictated by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and state media outlets, such narratives have excoriated the perceived double standards of the US and its allies, while pushing back against Western bias towards China.

Meanwhile, the US has taken a different tack, centring less on US-China tensions than on promoting a range of other issues among the Vietnamese public. Over the seven-month period, the US sought to highlight education and culture, accounting for about 68 per cent of a total 1,155 online posts. On the other hand, diplomacy and politics make up about 64 per cent of China’s 601 posts. Even though the US generated the most content on educational and cultural issues, eyeballs were focused elsewhere.

Kamala Harris’ Southeast Asia visit draws Chinese netizens’ ire

An analysis of the three most engaged Facebook posts during the seven-month period shows the US ones that attracted the most attention covered diplomacy and politics. Interestingly, public engagements zeroed in on the very theme China embraced to propagate its narratives: the anti-American trope.

When both countries sought to burnish their vaccine diplomacy campaigns in Vietnamese cyberspace, the US beat China by a wide margin in terms of positive public reactions, reflecting the fact the Vietnamese public prizes US vaccines over Chinese ones. Such sentiments were reflected in an analysis of Facebook posts and their average engagements on vaccine diplomacy that were among the most engaged content between January and July.

The contents of the Facebook pages of the US embassy and consulate were almost identical, but that was not the case for how China allocated its resources for online messaging. Unlike the embassy in Hanoi, the Facebook page of the Chinese consulate in Ho Chi Minh City deployed satirical cartoons, parodies, memes and sarcastic language to castigate the US agenda with “whataboutisms”.

Based on an analysis of the degree of public reactions to all Facebook posts, the Chinese embassy incurred the most “angry” emojis while its consulate registered the most “haha” ones, even though they both promoted the same narratives. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that online messaging employed by the Chinese consulate was more engaging for social media-savvy users.

At the other end of the spectrum, the US embassy and consulate attracted the most “love” emojis, suggesting their messages provided even more alluring eye candy to the public than posts from their Chinese counterparts.

How will US match China in Southeast Asia? Kamala Harris’ visit offers clues

The takeaway for China: the Vietnamese public is generally more receptive to US narratives. It would therefore be risky for China to ratchet up its blistering anti-US rhetoric in Vietnamese cyberspace, even though Beijing’s criticism of the US is sometimes legitimate.

Besides the latest mocking cartoon, two other waves of online backlash against anti-US narratives in Vietnam last year should have sent a clear message to Beijing.

In July 2020, the Facebook page of the Chinese embassy in Hanoi caused an online stir after posting a note from Global Times editor in chief Hu Xijin, warning Vietnam against siding with the US to contain China.

In the note, which was published on the 25th anniversary of US-Vietnam bilateral ties, Hu pointed to Washington’s “malicious intent” in pitting Hanoi against Beijing.

The note also warned the Vietnamese that the US could pull the rug out from under them. After a public furore, the note was taken down.

Four months later, the US and China posted statements on the Facebook pages of their respective embassies accusing each other of destabilising the global order.

The reaction online was revealing. In the comment sections of those Facebook posts, users who appeared to be Vietnamese overwhelmingly cheered the US statement while sneering at China’s response.

It suggests the Vietnamese public has different messages for the US and China.

The US focus on education and culture in Vietnam dovetails with facts on the ground. Various polls have attested to the strong positive sentiments among Vietnamese toward the US. The desire to live, study and settle in the US remains a key driver for Vietnamese, statistics show.

How China’s cooperation with Mekong countries can overcome a trust deficit

However, the US could enhance its appeal to Vietnamese by showing that Washington offers more than symbolism and posturing in defence and security cooperation with Hanoi.

China is unlikely to dial down its nationalistic rhetoric on foreign policy, particularly its anti-US narratives, but Beijing might at some point seek to soften its “chest-thumping” stance, as it seems to have been counterproductive in appealing to Vietnamese audiences.

Still, when it comes to the goal of making its image more “lovable” in Vietnam, Beijing has a long way to go. The reasons are not hard to fathom: public sentiments online may be protean and fickle, but anti-China sentiments have percolated and been amplified in the Vietnamese discourse. They are not fading away any time soon.

Dien Nguyen An Luong is a visiting fellow with the Media, Technology and Society Programme of the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore. This is an edited excerpt of an article titled ‘Comparing Vietnamese Responses to Chinese and American Public Diplomacy Efforts on Social Media’, published in ISEAS Perspective No 109.