Advertisement

China Briefing | The Evergrande saga marks the end of China’s long property boom

- Comparisons to how the collapse of US bank Lehman Brothers led to the Global Financial Crisis make great headlines but are flawed, as Fed chairman Jerome Powell has pointed out

- Beijing’s silence speaks volumes about its plans for reining in the overleveraged sector. The writing has been on the wall for debt-fuelled growth since 2016 when Xi Jinping remarked ‘houses are for living in, not for speculation’

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

17

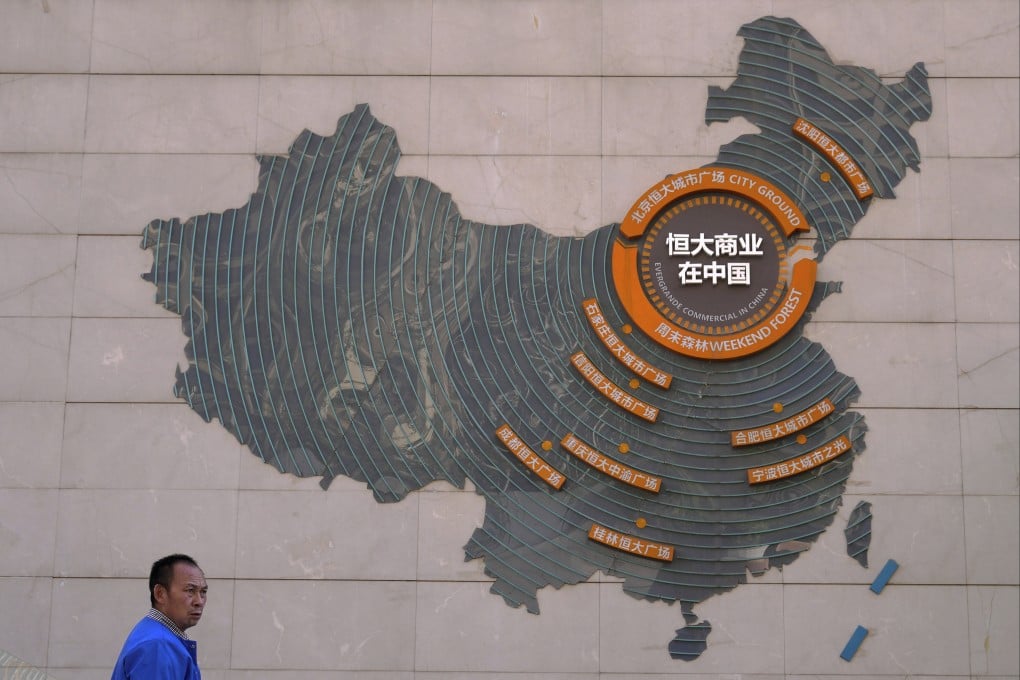

Back in 2017, billionaire Xu Jiayin was on a roll. He was crowned China’s richest man with a net worth of US$42.5 billion and his flagship China Evergrande Group was lauded as one of the world’s largest home builders with total assets of 2.1 trillion yuan (US$325 billion).

He harboured even greater ambitions: Xu started to dream about taking on Elon Musk and, in 2019, he announced a vision that China Evergrande would invest 45 billion yuan to build the world’s largest maker of electric vehicles within three or five years, just like he had started to build his property empire from scratch in 1996.

His cocky business slogan of “buy, buy, buy” was further illustrated that year by the high-profile announcement that he paid an economist an annual salary of 15 million yuan to embellish and trumpet his vision.

Advertisement

Merely four years later, China Evergrande is now being dismissed as the world’s most indebted property developer, with US$300 billion in liabilities, and is on the brink of collapse. And his electric car unit has not sold a single car, contrary to the plans for a roll-out this year. Share prices of the Hong Kong-listed China Evergrande and its car unit have plunged nearly 90 per cent.

Worries about the contagion effects have again spooked global investors who are not only concerned about China’s highly leveraged property sector but also its overall economic health as the housing market – including real estate development and related industries from steel to cement – accounts for 25 to 29 per cent of China’s GDP, by some estimates.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x