From Aukus to Nato and the EU, there are plenty of lessons from China’s Warring States period

- The Alliance of the Six Kingdoms once sought to take on a sole superpower, Qin: there are direct parallels today with the Western Bloc and China

- And while Chinese leaders have a long tradition of strategic thought, they should bear in mind that other nations have experience with history, too

Some time during the 4th century BC, two young men set out to seek fame and fortune in a chaotic China. They were close friends and had studied together, and together they waved their master goodbye.

Their names were Su Qin and Zhang Yi. And this was the period in Chinese history known as the “Warring States”, when seven kingdoms – Qin, Qi, Chu, Yan, Han, Zhao, and Wei – vied for supremacy. Ambitious men such as Su and Zhang travelled across China to offer their services as advisers to the various kings, in the manner of Machiavelli. When the friends came on the scene, one of the kingdoms, Qin, was growing into a superpower that threatened to overwhelm all the others.

In the service of Zhao, Su proposed a grand alliance of the Six Kingdoms against the lone superpower. He took the proposal to each of the other potential allies and, one by one, convinced them to join.

Meanwhile, Zhang went to the kingdom of Qin. In time, he offered Qin the strategy for defeating the Alliance of the Six Kingdoms: offer bilateral relations to individual members of the six to tempt them away. In the long run, Zhang’s strategy succeeded, and the Qin conquered the Six Kingdoms to unify China into the Qin Empire.

Did Aukus just torpedo Europe’s ‘united front’ to contain China?

She could see my point, which was that the Western Bloc in our time is now in the position of the Six Kingdoms vis-à-vis an increasingly powerful China, now in the position of Qin.

And Chinese leaders, doubtless familiar with the history of the Warring States, know the correct response strategy, namely Zhang’s: deal with each counterpart nation on a bilateral basis. One on one, China is larger and stronger than almost every other nation on earth.

03:51

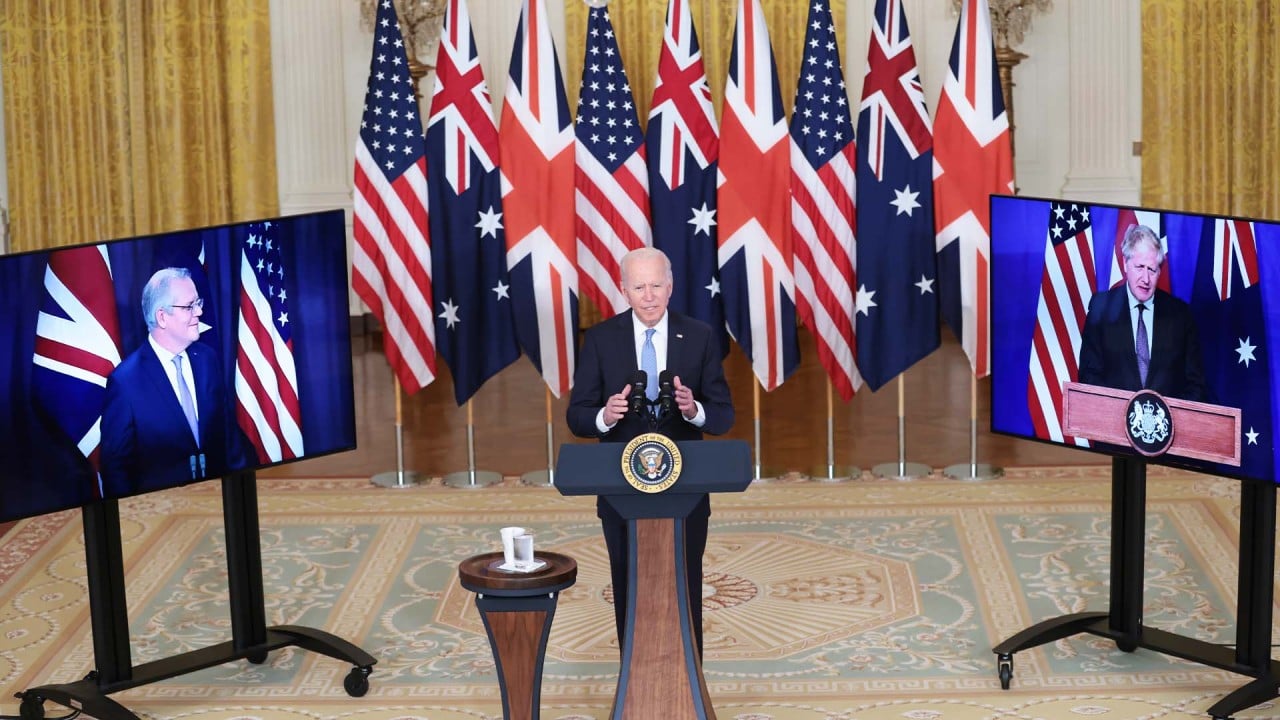

US, UK, Australia announce ‘historic’ military partnership in Pacific

Recently, for example, Beijing has sought to punish Lithuania for its friendliness toward Taiwan, among other issues. The disparity in size and power between Lithuania and China borders on the comical. Tiny if valiant Lithuania needs European solidarity to stand against the mighty dragon. The difficulty Lithuania faces is that – as the Qin discovered when dealing with the Six Kingdoms – multilateral alliances are by nature fractious and disputatious. The EU, having not long ago bade Britain a not-so-fond farewell, is clearly no exception.

The fractiousness was also on full display over Aukus. Australia, which also has been in China’s crosshairs recently, formed a new security arrangement with the United States and the United Kingdom, in so doing reneging on a prior deal with France. Paris was so upset that it recalled its ambassadors to Washington and Canberra, in an unprecedented move.

China points finger at Aukus as it rallies support to join CPTPP

One imagines that news of the recall amused leaders in Beijing. As Zhang Yi taught them, against adversaries linked in a multilateral framework, there are always fissures and grievances among them that the lone superpower can exploit.

But the lessons of the Warring States aren’t so simple.

For one thing, Su and Zhang were exceptional statesmen – there’s a reason Chinese students still learn about them. Su won the trust of all six kings, so much so that he carried each of the kingdoms’ chancellor’s seals. Just as there is a Nato secretary general today, so Su served as the secretary general of the Alliance of Six. While he held sway, the armies of the Qin dared not encroach on any of the member states, and even Zhang declined to make a move as long as his old friend was in power.

And are multilateral alliances truly weaker as a matter of course? The history of the Cold War suggests otherwise. In the wake of World War II, the US set up Nato on a multilateral basis despite being obviously the leading power of the Western Bloc. The Soviet Union, in contrast, blatantly dominated all the other members of the Warsaw Pact. Only one of these alliances still exists.

Furthermore, even as Chinese leaders rightly learn from their culture’s long tradition of strategic thought, they should bear in mind that other nations have experience with history, too.

A well-educated Chinese leader may have grown up reading the Records of the Grand Historian (also known by its Chinese name, Shi Ji) or the Stratagems of the Warring States (Zhan Guo Ce). But his Western counterpart has likely studied Herodotus and Thucydides. The History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides has long been a staple of America’s military academies as well as its elite universities.

After Aukus, the Quad’s quiet resolve gives China much to think about

In the long run, Athenian attitude drove many of the other Greek states into the arms of its arch rival, Sparta. And the Peloponnesian War ended with Athenian ruin.

The Kingdom of Qin might have prevailed, but Athens didn’t. History is a wonderful teacher, but, like the Delphic Oracle, it’s a tricky one as well. And being a great power can be a lovely thing – but it is never a simple affair to bestride the world like a colossus.