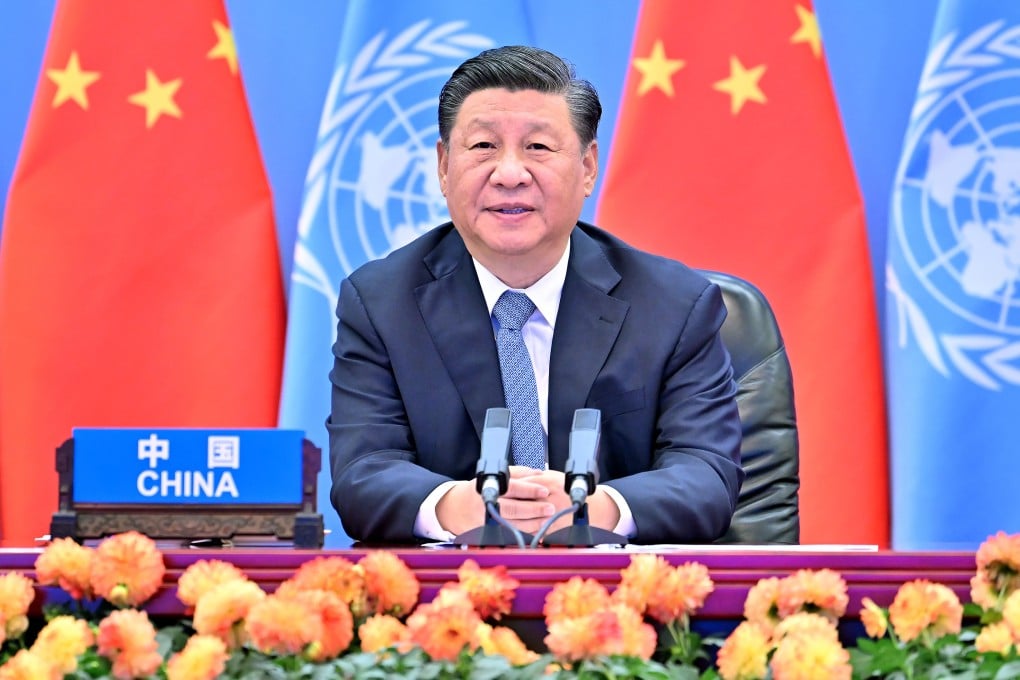

China Briefing | Rare party resolution will solidify Xi Jinping’s power, but leave China’s succession unclear

- The CCP is set to pass a resolution that will provide a further theoretical boost to Xi’s political standing, as a previous one did for Mao

- But the document is unlikely to address one of the Chinese leadership’s greatest uncertainties: leadership succession

In the Chinese Communist Party’s parlance, the words “historic resolution” carry special political significance and implications. Only twice in the party’s 100-year history have the leaders adopted the so-named documents at critical junctures to resolve major issues plaguing the party, altering the course of its history.

The first resolution, issued in 1945 and guided by Mao Zedong, marked the party’s break from the heavy Stalinist influences and established Mao’s thought as the guiding principle to lead the party forward.

In 1981, Deng Xiaoping orchestrated the second resolution to repudiate Mao for launching the “Cultural Revolution”, which resulted in turmoil and catastrophe. Although the document continued to uphold Mao’s thought as the guiding principle, it nonetheless strengthened Deng’s authority and united the party’s thinking on his policy of reform and opening up, which paved the way for China’s economic lift-off.

Understandably, the announcement has generated considerable interest at home and abroad. The wording of the document may provide a clear indication about Xi’s authority and standing. Some analysts have also speculated whether the third resolution will examine and reflect the party’s past lessons and mistakes like the two previous ones.

The new resolution will come roughly one year before the party’s 20th congress, estimated to take place in the autumn of 2022, when Xi is widely expected to seek a third term as party chief, thus breaking the de facto two-term limit.