Opinion | There was a time when China and the US were both liberal

- The usual assumption is that liberal ideals are uniquely Western; but Enlightenment writers borrowed freely from Asian sources

- Many liberal ideals can be found in The Morals of Confucius, including the primacy of reason, equality, and openness to opposing views

Liberalism is much in the news these days, but there is little agreement on what the term means.

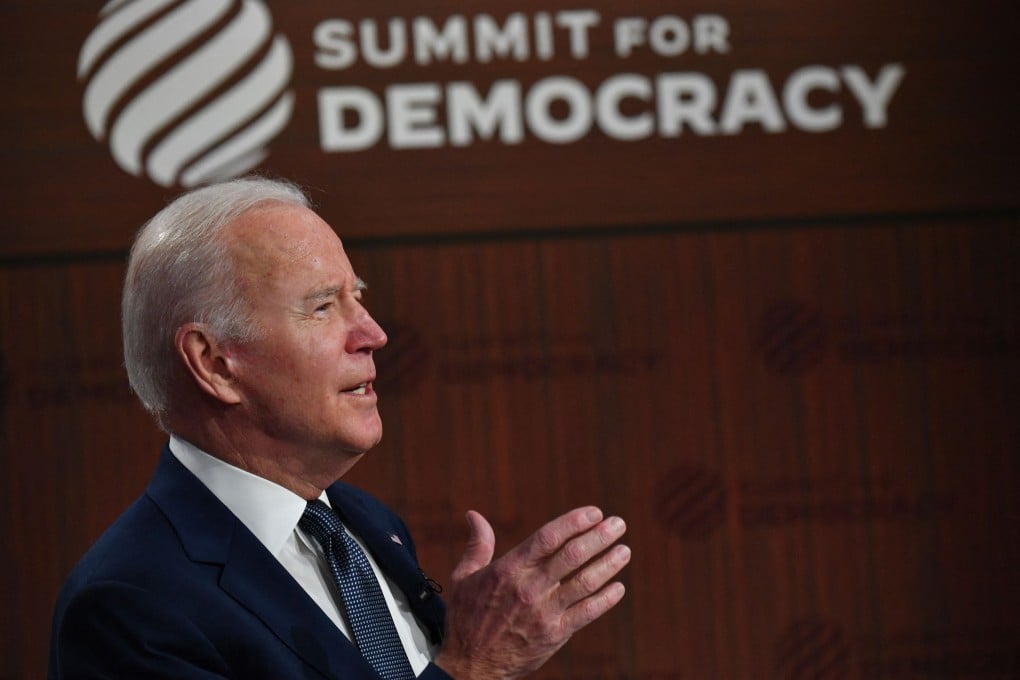

Joe Biden’s Democracy Summit last December was widely criticised for its double standards, with several of the invited nations embracing some variety of ethno-nationalist populism. Commenting for Al Jazeera on these illiberal invitees, former Barack Obama official Bruce Jentleson worried that the summit might damage, rather than enhance US credibility worldwide.

But democracies aren’t always liberal. Foreign Affairs recently republished Fareed Zakaria’s 1997 essay which showed how elections could install illiberal governments while maintaining the formal trappings of a democracy. Zakaria distinguished between plain democracies – which can be illiberal – and “Constitutional liberalism”, with its institutional checks.

Between the lines he implied another distinction between the Western liberal tradition, which he traced back to the Greeks, and that of non-Europeans.

“In countries not grounded in Constitutional liberalism … diverse groups with incompatible interests gain access to power and press their demands. Political and military leaders … realise that to succeed they must rally the masses behind a national cause. The result is invariably aggressive rhetoric and policies, which often drag countries into confrontation and war.”

Looking back some 20 years later, many Americans would have difficulty deciding if Zakaria’s description applies to some banana republic or to their own nation, where one of two political parties openly promotes far-right populism.