Advertisement

China Briefing | Upholding common law, tackling vested interests: Xi’s vision of Hong Kong strikes a chord

- The Chinese president praised Hong Kong for weathering the recent storm of unrest, as he doubled down on the ‘one country, two systems’ principle

- Local officials must now uphold the system of common law, tackle vested interests and strive to retain that which enhances city’s unique position and role

4-MIN READ4-MIN

21

Hong Kong’s return to mainland China 25 years ago was marked by a ceremony on June 30, 1997 that took place amid an unusually atrocious downpour – prompting many and various interpretations of what such a meteorological omen might mean.

Whether coincidence or not, the 25th anniversary celebrations of the handover on July 1 this year were likewise accompanied by inclement weather, as the grand occasion was buffeted by the headwinds of an incoming typhoon.

Occurring as it did at the exact halfway point of the 50-year “one country, two systems” principle under which Hong Kong is governed, Typhoon Chaba’s arrival triggered renewed readings of what the storm could possibly portend for the city over the next 25 years – or even longer.

Advertisement

Depending on who you ask, either doom or boom awaits.

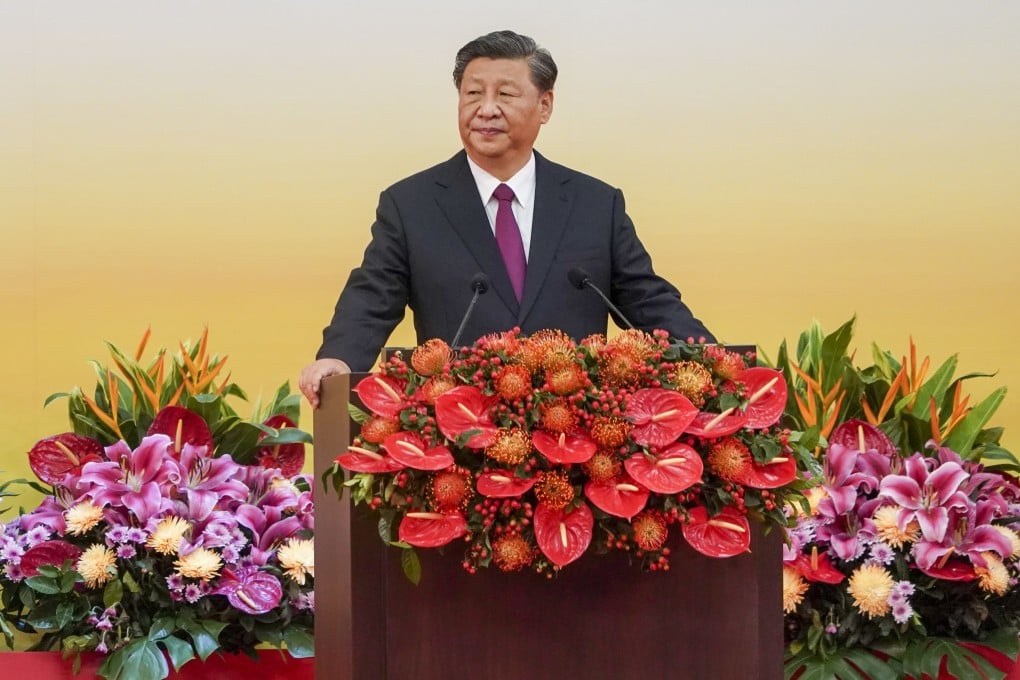

President Xi Jinping, presiding over the celebrations and the inauguration of the city’s new Chief Executive John Lee Ka-chiu, praised Hong Kong for showing “strong vitality” and having “risen from the ashes” after “the wind and the rain”. This meteorological reference was apparently used to describe the violent anti-government protests of 2019, which led to Beijing imposing a national security law and introducing electoral changes to ensure that only patriots would govern the city.

Advertisement

But for Western powers, including the United States and Britain – the city’s old colonial master – Hong Kong is fading fast, as it rapidly becomes just another mainland Chinese city with its promised autonomy eroded, and the rights and freedoms of the Hong Kong people dismantled over the past two years.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x