Advertisement

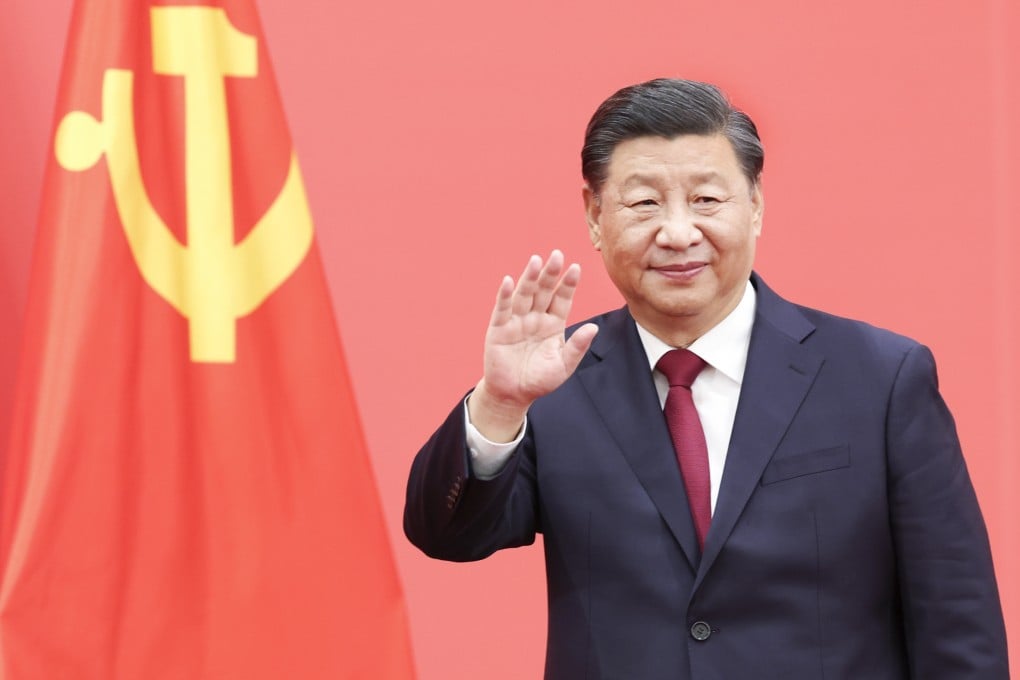

Back To The Future | Communist Party’s moment of crisis turned Xi Jinping from the ‘weakest’ to its ‘most powerful’ leader in history

- China’s long-standing norms, including retirement age and balance of power at the top, are set aside as Xi Jinping seeks to restore party discipline

- After taking office, Xi promised to crack down on corruption, which was rampant under former leader Hu Jintao

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

10

The recently concluded 20th Party Congress was exceptional because it shattered many long-standing conventions. These unwritten rules and customs were established over time after the Cultural Revolution to reduce party infighting, build consensus and avoid excessive concentration of power.

At the end of the Cultural Revolution, party elders like Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun found themselves inheriting a party and country torn by bitter political strife and chaos resulting from the excesses of Mao Zedong in his later years.

Deng and his colleagues realised that if they could not reunite a divided party and refocus their minds on economic development, the very survival of the People’s Republic of China and the Communist Party would be in doubt.

Advertisement

A set of unwritten rules and customs gradually formed around the turn of the century. These include the customary age rule to decide promotions to the Politburo Standing Committee – the highest decision-making body.

Any candidate over the age of 68 would be disqualified for promotion to this controlling group.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x