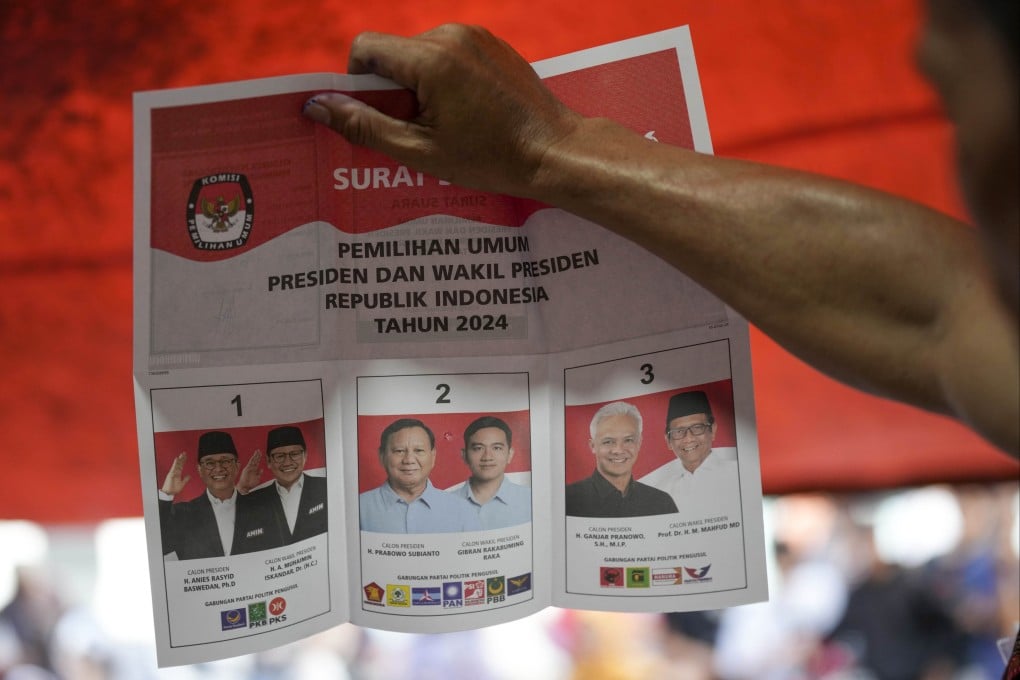

Asian Angle | In Indonesia, the art of winning elections can cost candidates an arm and a leg – or a kidney

- Polls are seen by some Indonesian voters as a ‘season of money’, as tens of thousands of candidates vie for spots in the house of representatives

- One legislative candidate’s revelation that he would sell his kidney to offer voters ‘tips’ underscores the extent of the illegal but increasingly commonplace practice

The electoral dynamics for legislative elections, particularly the practice of money politics – defined here as the exchange of material benefits (given to potential voters) for, or in the expectation of, receiving votes – has received less attention.

Erfin Sudanto, a legislative candidate in Bondowoso from the PAN party, recently caused a stir on social media when he revealed he intended to sell one of his kidneys to finance his campaign. He said he needed up to US$50,000, and that much of that sum would be spent on what he called “tips” to gain the support of potential voters.

Under Indonesian law, purchasing votes is illegal. Nevertheless, vote buying has become increasingly commonplace and is rarely dealt with by law enforcement. Some voters no longer see elections as windows of opportunity to express their political preferences but rather see them as a “season of money”.

Money politics has long been a part of Indonesian electoral politics, particularly in legislative elections, where tens of thousands of candidates compete for limited seats.

Many politicians lament the increased pressure on them to engage in vote-buying, claiming that such transactions have become part of everyday politics. They admit voters believe that whoever is elected will quickly forget their constituents after the election.

Before last month’s elections, many politicians and voters openly discussed vote-buying practices – terms such as “NPWP”, “golput” (spoiled vote or abstention) and berjuang (“struggle”) were widely circulated.