Asian Angle | Amid China tensions, Australia and Asean must iron out hard issues to preserve regional stability

- Australia and Japan can help Asean leverage Australian and the Quad’s resources to manage the more assertive aspects of China’s regional behaviour

- Canberra must also step up efforts to nurture its trade ties with Asean to ensure sustained relevance in their economic relationship

Both the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and Australia are part of various bilateral and multilateral frameworks aimed at enhancing regional architecture and fostering a conducive environment for open dialogue and mutual benefit. Australia now recognises Asean’s centrality in the Indo-Pacific.

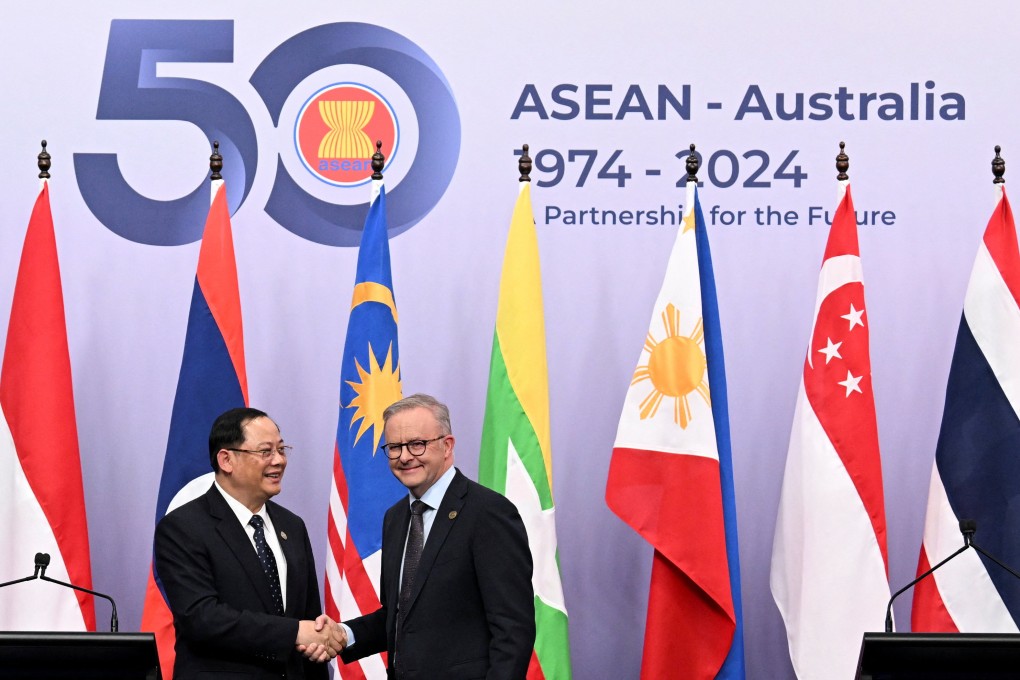

Yet even after the recent 50th anniversary celebrations at the Asean-Australia Special Summit held from March 4 to 6, Asean and Australia continue to face heightened risks as the international order veers towards multipolarity amid polycrisis.

To Asean, the rationale is clear: such US-led minilaterals could undermine its centrality and any cooperation with these minilaterals would rile China. While the member states cannot wish away minilaterals, they can nevertheless leverage these arrangements to their national benefit and regional stability.

There is a sweet spot here. After years of testy relations with Beijing, Australia is rebalancing its relationship with China, taking a more pragmatic turn towards trade normalisation. This would lead to greater regional stability, which Asean appreciates. However, Canberra and its formal allies – in particular, the US and Japan – want to continue to manage the more assertive aspects of China’s regional behaviour.