Advertisement

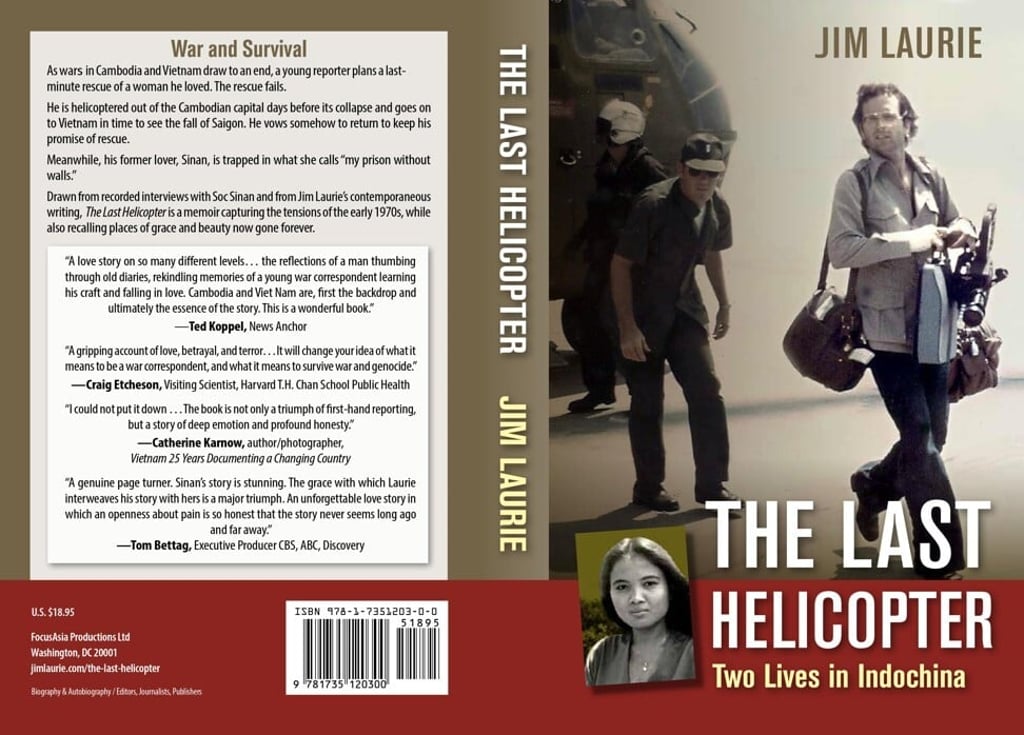

‘There is no prayer in revolution’: former Hong Kong-based reporter Jim Laurie remembers Cambodia, Vietnam conflicts in new memoir

- In ‘The Last Helicopter: Two Lives in Indochina’, Jim Laurie looks back on 1975 and the final days of the US-backed regimes in Phnom Penh and Saigon

- His eyewitness accounts are interwoven with the memories of Soc Sinan – a young Cambodian woman whom he loved but had to leave behind

Reading Time:6 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

In his new memoir The Last Helicopter: Two Lives in Indochina, long-time Hong Kong-based journalist Jim Laurie recalls the final days of war in Vietnam and Cambodia, and the attempted rescue of Soc Sinan, a woman whom he loved.

Helicoptered out of Phnom Penh days before the collapse of the US-backed Khmer Republic in 1975, Laurie reached Vietnam just in time to see the fall of Saigon – all the while vowing to return to Cambodia to save Sinan from one of the Khmer Rouge’s now infamous work camps.

Drawn from recorded interviews with Sinan and the author’s own contemporaneous writings, the book tells a story of lives and contrasting cultures that intersect in remarkable and unexpected ways, and of people bound together for a time, by war, pain, and the inability to forget.

Advertisement

Laurie, who worked as an Asia correspondent for NBC News and ABC News, also taught broadcast journalism at the University of Hong Kong from 2005 to 2012.

What follows is an excerpt from the The Last Helicopter, which is available on Amazon.com.

Advertisement

April 12, 1975

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x