Advertisement

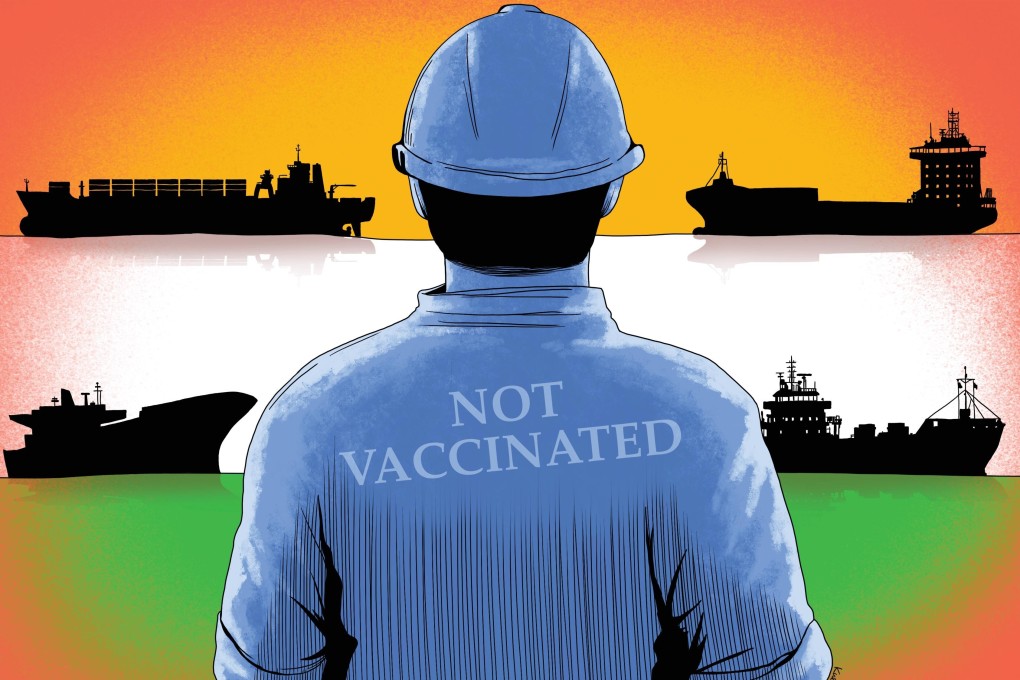

Indian seafarers left in limbo as coronavirus restrictions create chaos in shipping industry

- Difficulties securing vaccines mean seafarers face job losses as well as obstacles to returning home after finishing contracts

- Overworked crew members have been forced to stay on board even after their contracts expired due to a lack of crew change options

Reading Time:6 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

2

This is the fourth in a series of stories about the impact of India’s Covid-19 crisis on the Indian and Chinese economies and the global initiative to restructure supply chains.

O.F., a 44-year-old mariner who works for a Hong Kong-based shipping management firm, planned to be in Goa only until April, as part of a four-month break from his last seafaring stint which lasted for nine months.

But as of last week, he remained in his hometown on India’s west coast, a casualty of the country’s surge in Covid-19 cases that has resulted in some shipping companies shunning Indian crew for their vessels.

Advertisement

Their decision stems from more than 24 countries including Britain, the US and Australia banning travellers from India, preventing the companies replacing existing workers on cargo ships. Several major ports in mainland China, Singapore and the UAE have also barred crew changes for ships arriving from India.

O.F. said his company told him to get vaccinated so he could rejoin his vessel. In April, he used the government app to book his first vaccination appointment, which he got only this month. But with India short on vaccine supplies – only 3.8 per cent of its 1.35 billion population have been fully vaccinated – O.F. will have to wait until August for his second shot.

Advertisement

“The Indian government termed seafarers as key workers last year, but why were we not a priority for vaccination?” he said. “Now I may end up losing this job.”

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x