As Dutch say sorry for atrocities in postcolonial Indonesia, time for Jakarta to address its own dark past of racial violence, genocide?

- A study that shines light on Dutch atrocities after Indonesia’s declaration of independence has shocked the nation and prompted PM Mark Rutte to apologise

- It has also stirred debate about Indonesian attacks on racial minorities during that time as well as a later genocide against suspected communists and ethnic Chinese in the 1960s

A team of 115 researchers in the Netherlands and Indonesia last week published the findings of their six-year study, which concluded that the Dutch government and leadership had “deliberately condoned the systematic and widespread use of extreme violence by the Dutch armed forces” during the war, which lasted from 1945 to 1949. Indonesia has dubbed that period as the revolutionary era as it took place shortly after the declaration of independence on August 17, 1945, which ended three and a half centuries of colonisation by the Dutch.

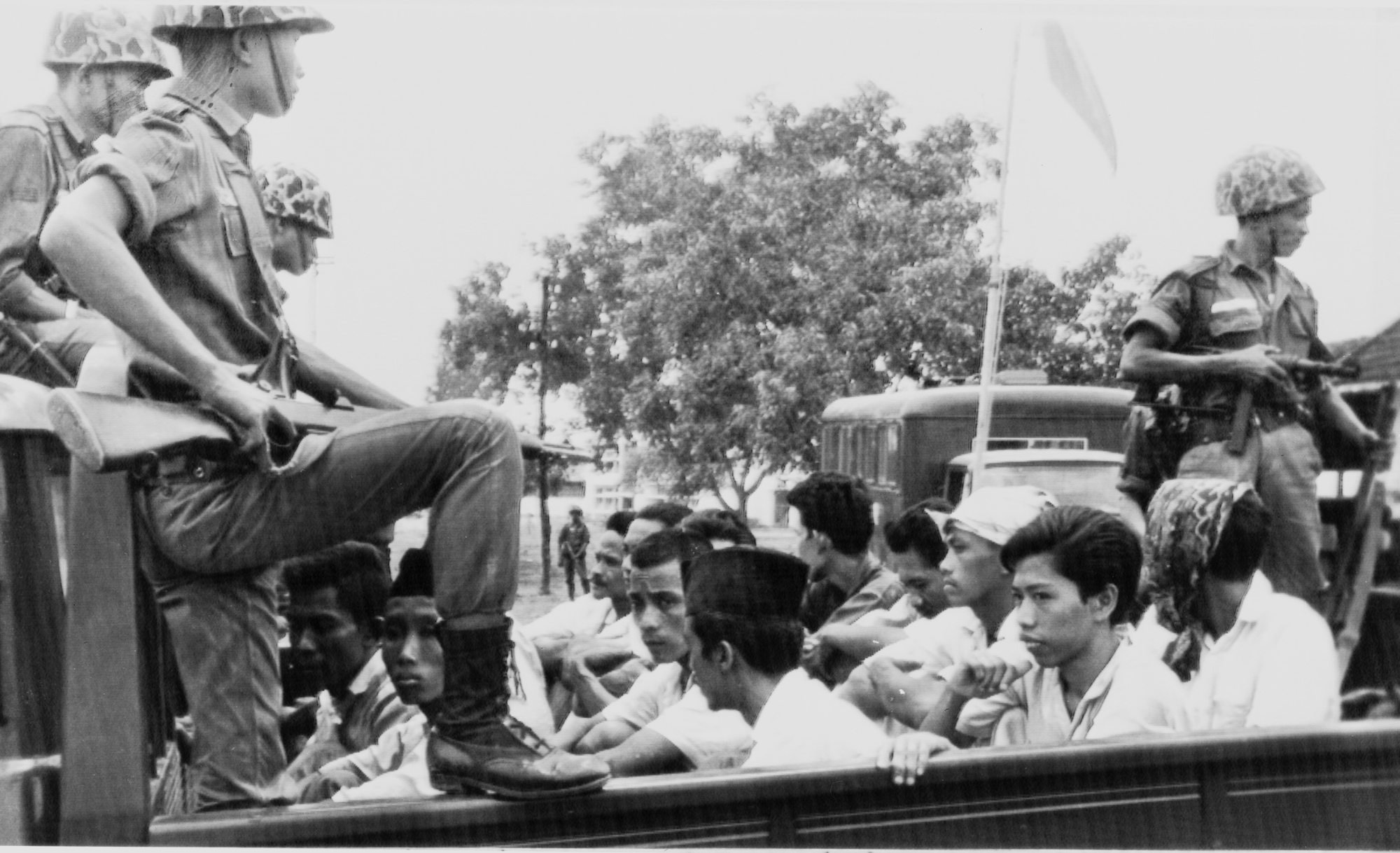

According to the study, upon returning to its former colony with the help of Allied forces, the Dutch carried out “extrajudicial executions, ill-treatment and torture, detention under inhumane conditions, the torching of houses and villages, theft and destruction of property and food supplies, disproportionate air raids and artillery shelling, and what were often random mass arrests and mass internment”.

“It was condoned at every level: political, military and legal. The reason for this was that the Netherlands wanted to defeat the Republic of Indonesia – which had declared independence on August 17, 1945 – at any cost, and was prepared to subordinate almost everything to this goal,” said the study, which cost 6.4 million euros (US$7.25 million).

The study’s findings last week caused waves in the Netherlands, more than 50 years after a sensational television interview in 1969 in which the veteran trooper Joop Hueting admitted that he and other soldiers had “committed war crimes” in the Dutch East Indies, Indonesia’s colonial name. The official Dutch line has in the past been that its forces there were involved only in isolated incidents.

The Netherlands’ Prime Minister Mark Rutte apologised to Indonesia last week, saying: “We have to accept the shameful facts. I make my deep apologies to the people of Indonesia today on behalf of the Dutch government.”

‘Tell the truth’: UK confronted over role in Indonesia’s 1965 genocide

‘Bersiap’ controversy

The study was published following a months-long controversy over the two nations’ different perspectives on the sub-period referred to as “bersiap” [‘be prepared’], within the four-year revolutionary war. The controversy stemmed from the Amsterdam-based Dutch Royal Museum’s use of the term in its ongoing exhibition titled “Revolusi! Indonesia’s Independence”, which highlights Indonesia’s postcolonial history in the 1945-1950 period.

The museum, also known as the Rijksmuseum, invited Indonesian historian Bonnie Triyana as a guest curator for the exhibition. Triyana argued in an opinion piece for the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad on January 10 that the term should not be used for the exhibition as it “takes on a strongly racist connotation”.

According to Agus Suwignyo, a historian from the University of Gadjah Mada (UGM) in Yogyakarta, bersiap refers to a post-independence period from 1945 to the end of 1946, during which Indonesians launched violent attacks against white civilians, Indo-Europeans, Malukans, Chinese, and other groups they deemed to be on the side of the coloniser.

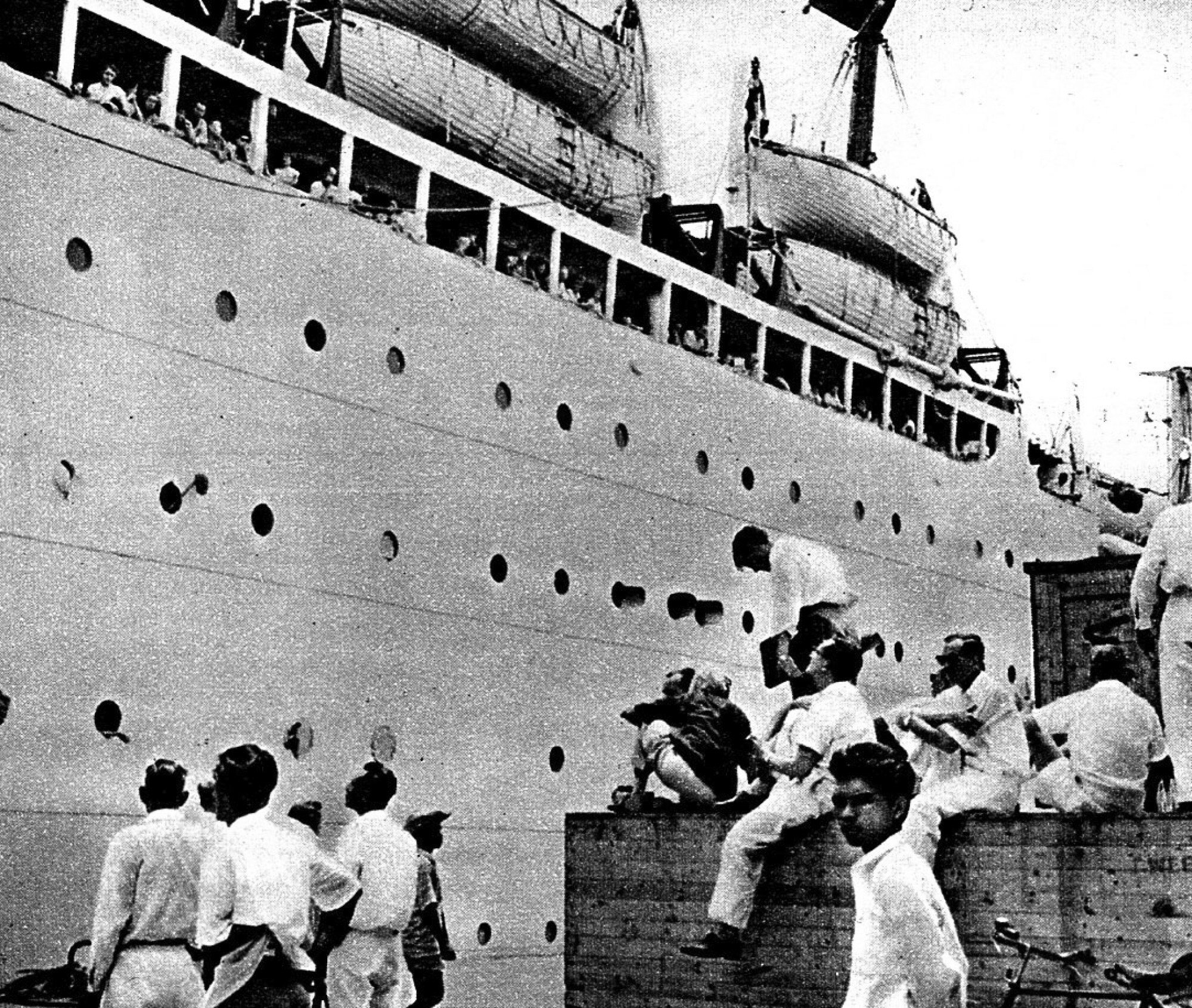

While bersiap is an Indonesian word, the period it refers to it is relatively obscure in the collective memory of Indonesians, who generally lump in the sub-period with the revolutionary war, he said. Europeans and Dutch-Indonesians were detained in concentration camps during the Japanese occupation, and were eventually released after Japan surrendered to the Allied forces in 1945, only to find out that their kampung or neighbourhoods had been occupied by other residents who were mostly poor.

In the eyes of the Dutch, “bersiap” was used as a battle cry among Indonesians before they launched attacks against the newly-released Europeans and Indo-Europeans, as well as the Malukans and Chinese. From the Indonesian perspective, the attacks were launched to defend the country’s newly-gained freedom.

Why fears of communism, anti-China sentiment are a potent mix in Indonesia

“In 1945, there was widespread poverty and hunger caused by Japanese occupation. In the eyes of many Javanese, the groups of people whose financial status remained stable at that time were the Chinese, Indonesians of Dutch descent, the Malukans, as they saw them as the representation of the enemy. They were seen as siding with the Dutch, so they became the target of mob rage,” Agus said.

Thus, banning the term in the “Revolusi” exhibition could be a recipe for disaster for the museum, as doing so could be viewed as dismissing the trauma endured by victims of the attacks. For his opinion piece, Bonnie was reported to the police for alleged defamation and incitement by the Federation of Dutch-Indies People, which represents descendants of people from the Dutch East Indies who were targeted by Indonesians during the bersiap period.

“The Europeans and the Indo-Europeans who were sent to concentration camps during the Japanese occupation in Indonesia, the Malukans who fled to the Netherlands in the 1950s … they were not recognised as victims of the war in the Netherlands, unlike the victims of Nazi Germany. They also felt like second-class citizens as, upon arrival in the Netherlands, they did not speak the language well and they were given poor housing by the government. They felt crushed by the ‘bersiap’ controversy,” said Aboeprijadi Santoso, an Indonesian freelance journalist who has been living in Amsterdam for more than 50 years.

However, insisting on using the racially-charged term can also be seen as offensive. The Committee of Dutch Honour Debts, which advocates for compensation for Dutch war crimes, reported the Rijksmuseum, its director Taco Dibbits, and curator Harms Stevens to the police for using a racist term and “historical falsification”.

Jacobien Schneider, a spokesperson for Rijksmuseum, told This Week in Asia that the museum “acknowledges and presents” the violence that took place against both sides of the revolutionary war.

The government must also recognise that its revolutionary history contains a bitter side

“We agree with the guest curator that one specific term for all the violence that took place during that period is not sufficient – as stated in his op-ed article. We do use the term in the exhibition and give a historical context at the exhibition, as well as other forms of violence in that same period,” Schneider said.

“The exhibition acknowledges and presents both the violence that took place in this period against Eurasian, Dutch, Malukan, Chinese and other people who took, or were suspected of taking, the Dutch side; and the violence that took place against other population groups, including Indonesians, in the same period.”

The study estimated that around 5,300 on the Dutch side were killed during the four-year war, including a considerable number of Indonesians in Dutch service. In the bersiap period, it is estimated that the number of deaths reached almost 6,000 Europeans, Indo-Europeans, Malukans, Minahasans, Timorese and other Indonesians on the Dutch side. In the seven months following the second Dutch offensive in December 1948, at least 46,000 Indonesian combatants were killed, the study said.

What’s next after the apology?

In Indonesia, the apology offered by the Dutch prime minister landed with a thud, with a Foreign Ministry spokesperson saying that it was “studying the documents [of the study] so that we can fully interpret the statement delivered by PM Rutte”.

The English-language newspaper The Jakarta Post on Monday published a column suggesting the government “return [the apology] to sender, with a thank-you note”, saying that more important than the apology was “what the Dutch government and society intend to do with the findings of the study”.

The paper also called for Jakarta to reveal and own its dark past.

“More than the apology offered by PM Rutte, Indonesia could learn a thing or two from this episode too. We also need to revisit our history and bring all the skeletons out of the closet. Besides the atrocities committed in the 1940s, there have been other violent episodes since independence that we have yet to fully comprehend or even recognise,” it said.

Historian Agus Suwignyo said the new study provided an opportunity for Jakarta “to be a gentleman” and admit that there were indeed racially-charged attacks during the post-independence fighting.

“The government must also recognise that its revolutionary history contains a bitter side. They need to recognise that there were attacks against some races that were perceived to be on the Dutch side,” he said.

“Indonesia should also dare to reveal just how gross the violence was during that period.”