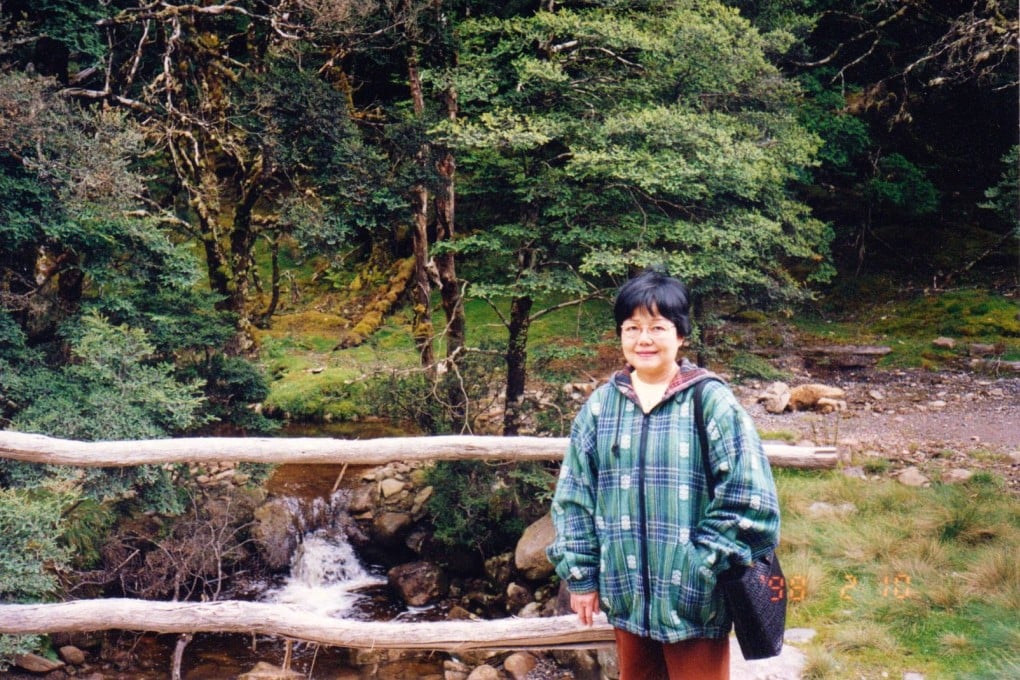

Indonesian-Chinese writer Marga T on guilt of having been born a girl: ‘it gave me cancer’

- In her latest and most personal work, the celebrated author ‘cleanses’ her soul as she opens up on her traumatic childhood, her mother’s death, and dealing with abuse

- The 79-year-old also reflects on her long career as an ethnic Chinese writer whose success came despite oppression against the community by ex-dictator Suharto, in this rare interview with This Week in Asia

With a career spanning more than half a century, Indonesian-Chinese writer Marga T is one of the country’s most prolific authors.

Born in Jakarta to ethnic Chinese parents in 1943, she showed an early gift for writing, with her first two novels, the romance titles Karmila and Badai Pasti Berlalu (The Storm Will Surely Pass), being instant hits.

But perhaps the most personal of all is her latest work, If Only, a poignant memoir “about the compulsory duty to have a son, and the tragic consequences for the family when no son was born”, she tells This Week in Asia in a rare interview.

In 1952, Marga’s mother died after giving birth to a sixth daughter. Marga was only nine then. Being the eldest, she bore the guilt of having been born a girl, as her father had expected to have a son so he could carry on the family’s surname.

“I was accused of having caused her death,” she says.