Return of ‘trashy tourists’ to Bali spotlights mass tourism’s double-edged sword

- From complaining ‘Karens’ to naked influencers, there’s been a rash of reports about badly-behaved foreigners since Bali reopened to overseas visitors in March

- The Indonesian resort island’s economy relies on tourism, but activists say ‘trashy tourists’ who disrespect the local culture and traditions aren’t welcome

Bali is back – but so are the tourists’ shenanigans.

The Indonesian resort island has seen a rash of reports about badly-behaved foreigners since it fully reopened to international tourism in March.

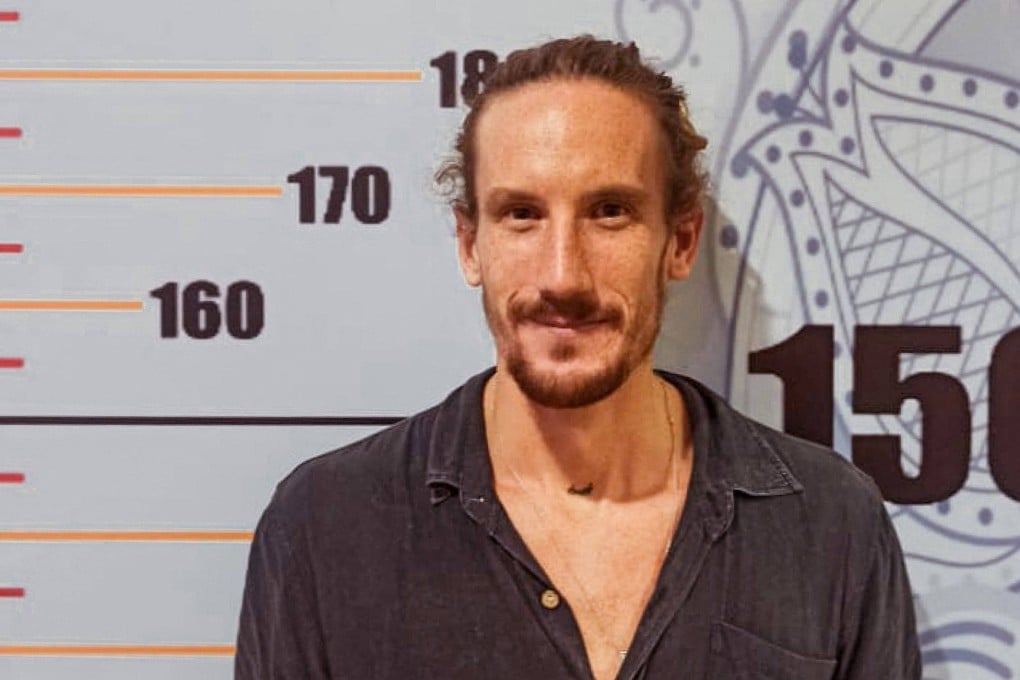

Over the past month, a Canadian and a Russian have been deported for public nakedness, a foreign tourist went viral for complaining about beach vendors, and an Estonian pageant contestant made waves after she accused the police of being corrupt.

The rash of incidents underscores how tourism has become a double-edged sword for the Hindu-majority island, which is nevertheless economically dependent on the sector.

“Bali does need tourists. But if they break our norms and rules, we should educate them so they do not go too far. If they’re still stubborn, we should deport them,” said local entrepreneur and activist Niluh Djelantik on Instagram. “Let’s maintain dignity and respect our land of birth together.”

Vexed by vendors

Last month, a short video showing a white woman complaining about the tourist mecca of Kuta Beach, which she said was “the worst”, sparked a debate after it prompted the island’s authorities to round up about 50 beggars and homeless people living in the area.