Was India’s Taj Mahal a Hindu temple? Only if you believe the revisionist conspiracy theories

- Nearly 400 years after its construction, the Mughal-era landmark has become the latest target of historical revisionism in increasingly polarised India

- A member of PM Narendra Modi’s Hindu-nationalist party challenged the site’s history – a case some legal experts say could go all the way to the Supreme Court

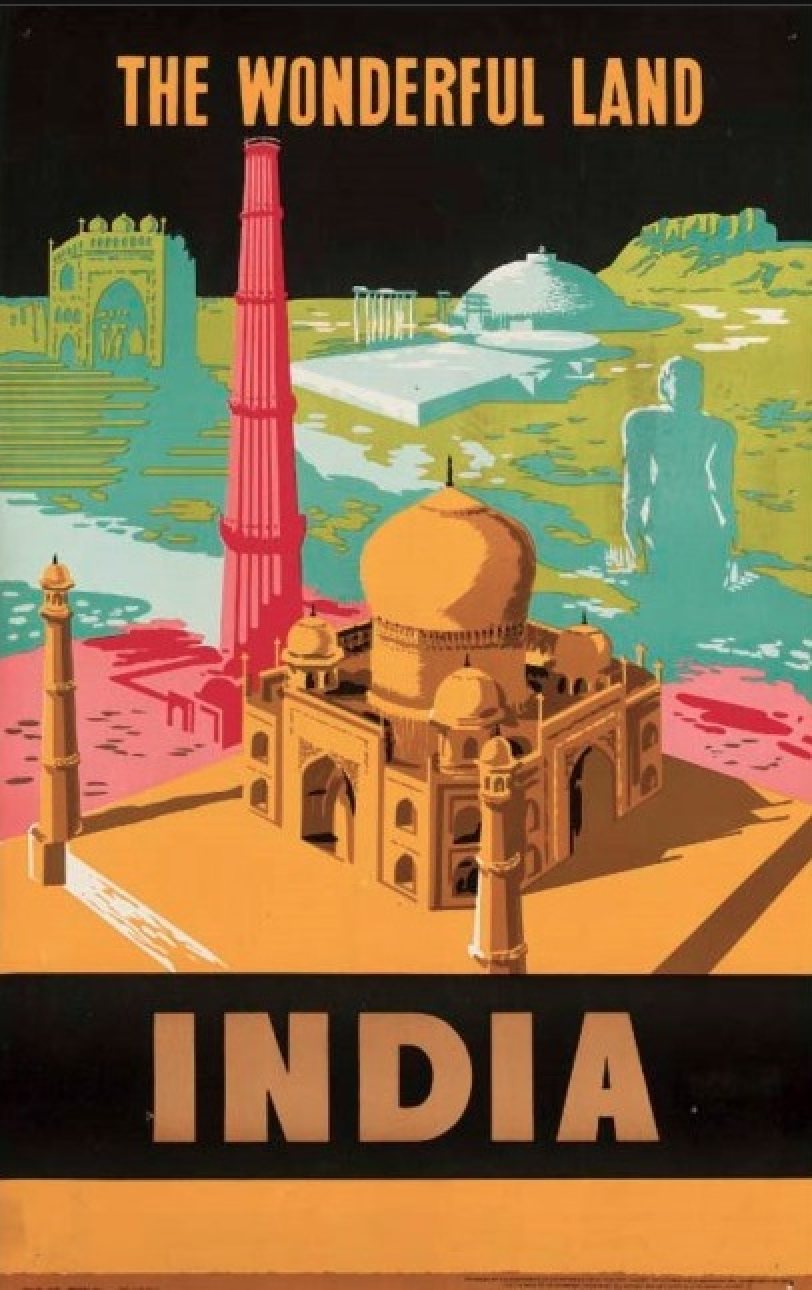

Decades of photographs, film appearances and tourism campaigns have cemented the celebrated structure’s hold on the public imagination.

Even when seen on a faded 1950s tourism poster in the corner of a Rajasthan tea shack – its marble-white dome and towering minarets turning to yellow in the scorching desert heat – the Taj Mahal still beckons to travellers from across the ages.

It is India writ large. Or, as historian Rana Safvi puts it: “The Taj Mahal is not a Hindu or a Muslim monument, it is an Indian monument, the one which represents India all over the world”.

But that universal appeal has been called into question in recent years, on the back of a historical revisionist’s decades-old claim that the Mughal-era mausoleum was built atop a Hindu temple.

In Modi’s India, Muslim rulers of the past ‘can’t be heroes’

The court dismissed the petition, with judges calling the issue “non-justiciable” and warning petitioners not to make a mockery of India’s public litigation system that allows unaffected third parties to file cases on others’ behalf. But it and similar pending court cases show just how much traction the theories of P.N. Oak – who also claimed that the Vatican, Kaaba and Westminster Abbey were originally Hindu temples – have gained in the age of WhatsApp and reactionary Hindu-nationalist discourse.

Nevermind that the Archaeological Survey of India has published photos showing that the Taj Mahal’s 22 doors lead nowhere except a long, continuous arched corridor.

Oak, who died in 2007, first published his Taj Mahal theory in the 1970s. “Nobody took him seriously” then, Safvi said. That’s not the case any more.

‘Tejo Mahalaya’

Historical documents and farman (official decrees) from the 17th century show that the land the Taj Mahal was built upon previously housed a riverfront estate belonging to Jai Singh, a senior general and minor royal of the Mughal empire.

Oak, however, claimed the mausoleum was built atop an earlier temple to the Hindu goddess Durga called “Tejo Mahalaya”. His book The Taj Mahal is a Temple Palace was out of print for years, but found a new audience among Hindutva ideologues after being republished in 2003.

The debunked temple theory picked up steam after Modi’s BJP took power in 2014, ushering in a wider campaign aimed at “reclaiming” India’s Mughal-era and Muslim architectural heritage from what right-wing activists label a foreign invader’s attempt to usurp and supplant Hindu civilisation.

Dozens of other mosques have had their legitimacy questioned by activists in the years since. And though Allahabad High Court on May 12 dismissed the latest BJP-led petition casting doubt on the Taj Mahal’s origins, lawyer and former legal journalist Areeb Uddin Ahmed told This Week In Asia that more challenges may lay ahead.

“The latest petition was not concerned about the origin of the structure, it was more about the locked rooms of the Taj Mahal,” he said. “Hence, there might be a possibility – taking into account the litigation that is going on before various courts in Varanasi, Mathura, Madhya Pradesh and so on – of this episode recurring.”

There are at least five legal actions concerning Muslim-Mughal heritage currently working their way through India’s courts, each a product of an ultranationalist propaganda campaign being waged against historical truth.

Even if they are all dismissed by lower courts, “they can move to the Supreme Court and appeal,” said Supreme Court advocate Anas Tanveer. “And I think given the agenda they are pursuing they will be doing it.”

A monument to love

Commissioned in 1632 by Emperor Shah Jahan (1592-1666) as the final resting place for his beloved wife Mumtaz Mahal, who died the year before, the Taj Mahal represents the pinnacle of Mughal-era architecture.

Famed for its white, domed marble mausoleum, it is in fact an extensive funerary complex of buildings and gardens that historian Safvi said was so much “more than a tomb”. “Built on the theme of death, resurrection and paradise, it also acted as a statement of [Shah Jahan’s] imperial vision,” she said.

The emperor, who was also buried at the Taj Mahal upon his death, chose a plot of land on the Jamuna river within sight of his imperial palace.

A farman dated December 23, 1633 shows that four havelis (manor houses) were gifted to Jai Singh by the emperor in exchange for the riverfront estate over which the mausoleum was subsequently built. The land had been gifted to Jai Singh’s grandfather Maharaja Man Singh – head of the Hindu princely kingdom of Jaipur and a key ministerial member of the emperor’s court – by the Mughal emperor Akbar, who was Shah Jahan’s grandfather.

Designed around a layout inspired by Islamic architecture known as hasht bihisht (eight paradises) the mausoleum of Mumtaz Mahal and Shah Jahan was decorated with precious and semi-precious stones using a naturalistic inlay technique called parchin kari.

Starting in the 19th century, the Taj Mahal became firmly associated with India as a whole in the European imagination as paintings, and later photographs, of the mausoleum were brought back by British colonialists.

Post-independence, it became the centrepiece of India’s tourism outreach campaigns and miniatures of the monument, made from a similar white marble, have at times been given as official gifts to visiting diplomatic delegations.

Bowel cleanse for better DNA: the nonsense science of Modi’s India

By the 1960s, references to the love story behind the Taj Mahal were being peppered throughout the dialogue and songs of multiple Hindi movies, some of which used it as a backdrop, and in 1982 it was recognised by Unesco as a World Heritage Site.

More than 7 million people visited the landmark in 2018-2019, the last year before the Covid-19 pandemic for which Culture Ministry figures are available, including some 800,000 from abroad – spending about 865 million rupees (US$11.2 million) at the site in total.