Was Indonesian freedom fighter Kapitan Pattimura actually a Muslim? Conspiracy highlights rising historical revisionism

- An Islamic preacher has claimed the 19th century anti-colonialist wasn’t Christian, as Indonesians are taught, but a Muslim cleric called Ahmad Lussy

- Such revisionist claims have become increasingly popular in the world’s largest Muslim-majority country in recent years, scholars say

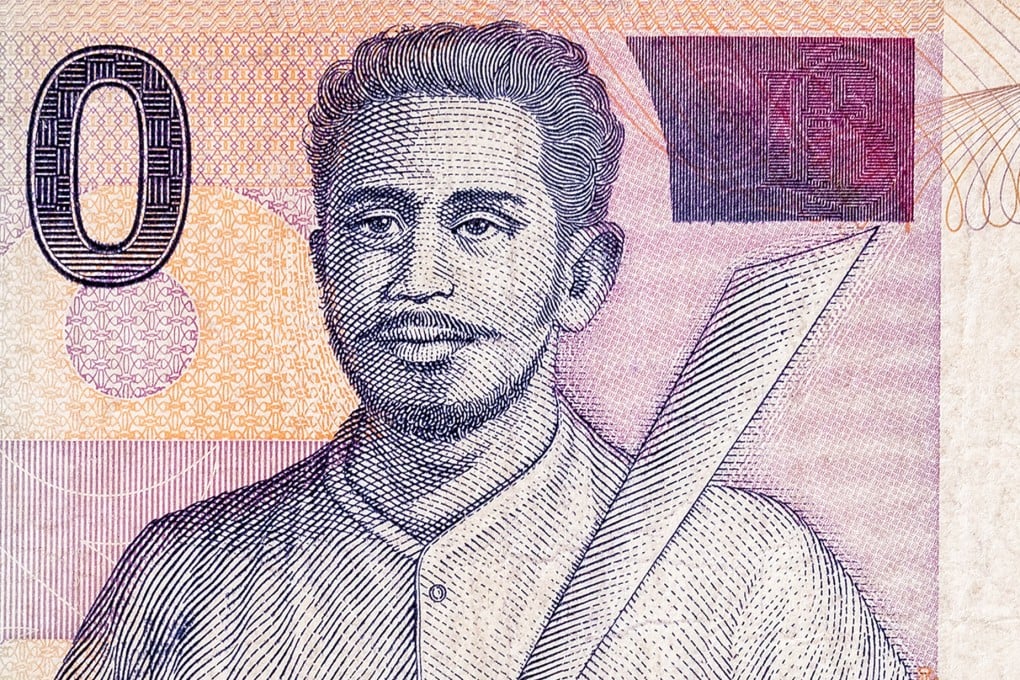

Indonesians are taught in school that Pattimura was born Thomas Matulessy in 1783 on Seram in the Maluku Islands and was a Christian – like many of that area’s inhabitants to this day.

The islands were part of the Dutch East Indies at the time, but fell under British rule for a short but turbulent period in the 1810s against the backdrop of the wider Napoleonic Wars.

History books state that Matulessy served under the British, later taking up the ancestral title Pattimura to lead a revolt against the Dutch after the Maluku Islands were returned to them in 1814. His uprising was ultimately unsuccessful, however, and he was hanged for treason in 1817.

Yet in his sermon, Adi Hidayat claimed to know better than most mainstream historians.

“His name wasn’t Thomas Matulessy but Ahmad Lussy. He was a freedom fighter and a Muslim cleric,” the conservative preacher told his audience.

Hidayat’s attempt to rewrite Indonesian history split the country’s social media users, with some making light of the preacher’s sermon while others branded anyone who disagrees with him an “Islamophobe”.