Sri Lanka’s transgender community in need of ‘life-saving assistance’ amid economic crisis

- Many transpeople can no longer afford rent, drugs for hormone therapy and struggle to find employment as country is mired in crisis

- Struggles of transpeople are further exacerbated in conservative Sri Lanka, where they face social stigma and prosecution

“I cannot go hungry. I had to do something else to earn money; to be able to buy food and pay the rent. So these days I do deals,” the 33-year-old said, referring to sex work.

The setbacks faced by the already-marginalised community have been exacerbated by the country’s economic crisis, cutting off their access to vital hormonal therapy and rendering them unemployed and homeless.

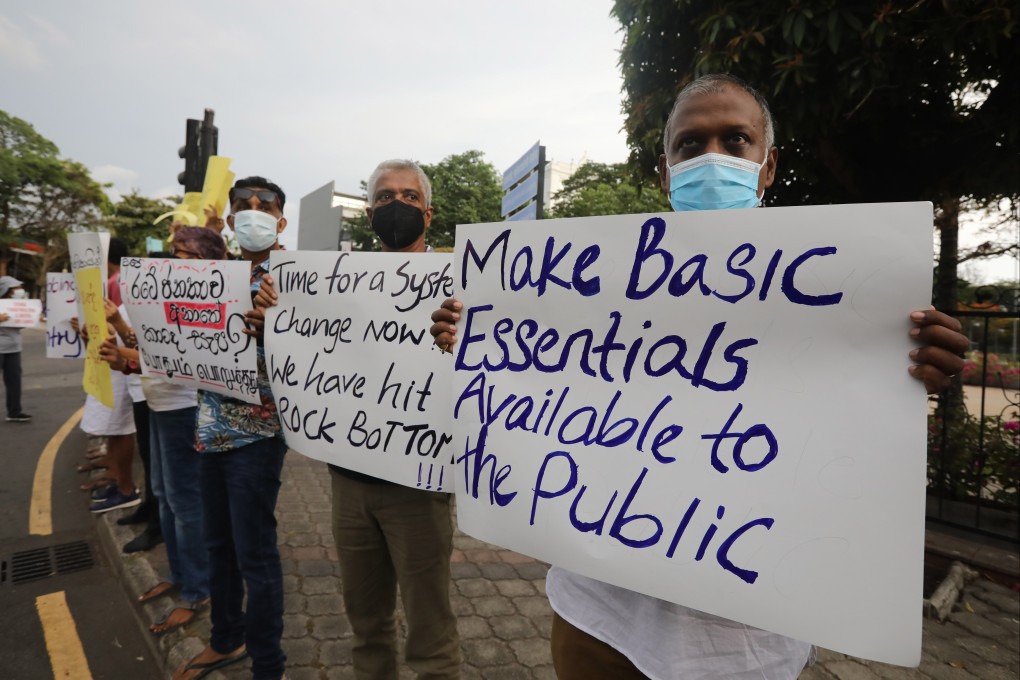

Sri Lanka’s 22 million people have undergone months of food and fuel shortages, extended blackouts and soaring inflation. In April, it defaulted on its US$51-billion foreign debt.

In June, the United Nations said that nearly 5.7 million people in Sri Lanka were estimated to be in need of “immediate life-saving assistance”. By July, year-on-year food inflation rose to 90.9 per cent, and inflation stood at 60.8 per cent, even as the country underwent a rocky leadership change following mass protests.