A tale of two cities: Singapore, Hong Kong and their contrasting paths

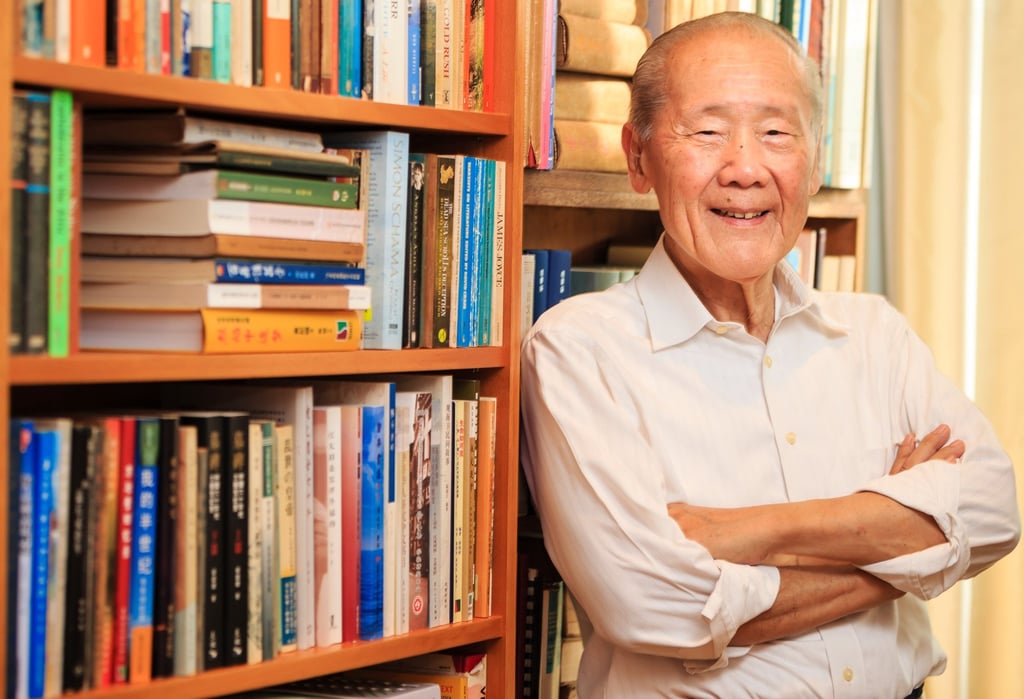

Historian Wang Gungwu reflects on how political legacies have shaped Hong Kong and Singapore, two of Asia’s economic ‘tigers’

For Hong Kong, it consisted mainly of Chinese people who spoke Cantonese and thought they knew how to deal with British officialdom. Mandarin speakers were still regarded with suspicion or condescension.

The city had its own pluralist features, greatly divided along many different political lines. They were prepared for the city’s return to a China homeland, but there were many who hoped that a reformed People’s Republic of China might eventually grow a system more like that of Hong Kong’s.

In contrast, Singapore was a republic with a Chinese majority committed to a multifaceted Chinese-Malay-Indian-Others (commonly abbreviated as CMIO) nationhood. What made the task of its leaders so challenging was that each of the four groups was diverse and pluralistic in its own way. From the start, the legacy of British democracy was to provide legitimacy to a strong government that could manage this successfully.

Founding prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, believed that stable political power was essential to create the prosperity the port city desperately needed and that could only be achieved at a cost. His successor, Goh Chok Tong, looked out for new directions for the people to benefit more directly from what had been achieved. This was evident in the policies developed during the 1990s.