We’ll never forget you, Britain told Hong Kong with a straight face

Britain’s promises not to forget Hong Kong were forgotten almost as swiftly as its hurried departure. Locals were likewise quick to adapt

The day after presiding over Britain’s part in the ceremonies for the Hong Kong handover, Prince Charles found himself on the royal yacht Britannia making its way to the Philippines. By all accounts he had not had a happy time during his brief visit and, in widely leaked remarks, reflected on his discomfort with his Chinese counterparts who he privately described as being a bunch of “waxworks”.

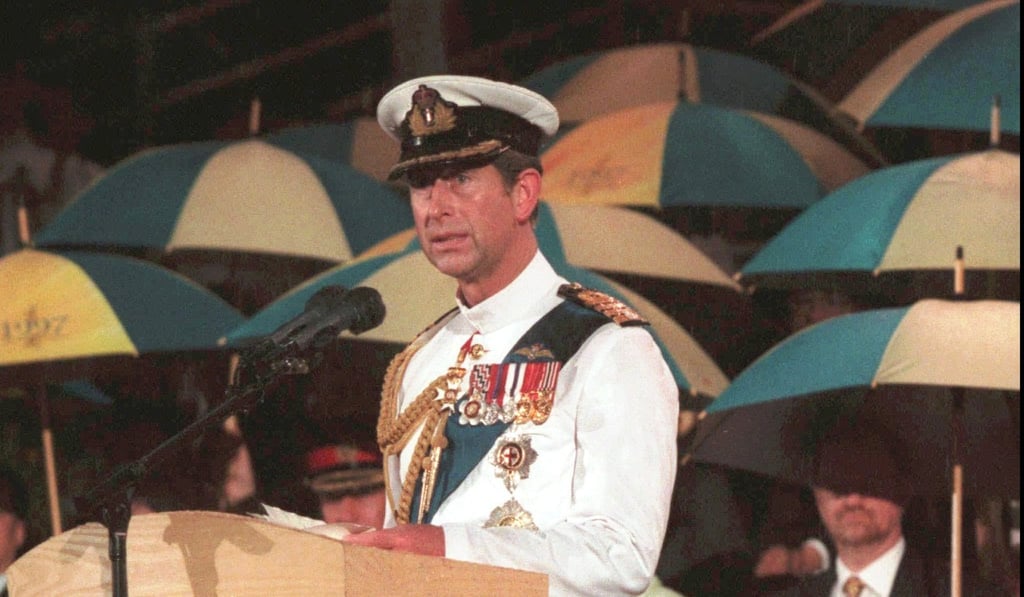

The prince had endured a rain-drenched ceremony at the Tamar barracks and looked far from happy when he arrived at the main handover event in the newly built Convention and Exhibition Centre.

Ahead of the ceremony Robin Cook, Britain’s then-foreign secretary, assured us journalists that the colony’s return to Chinese rule most certainly did not mean that Britain’s interest in Hong Kong was at an end; the assembled British hacks gave each other knowing looks.

At the handover ceremony itself, Prince Charles dutifully read out his script echoing the foreign secretary’s remarks: “we shall not forget you”, he promised, adding “our commitment and our strong links to Hong Kong will continue and will, I am confident, flourish as Hong Kong and its people continue to flourish”.

Just a couple of hours later he was gone. Tony Blair, the prime minister, was also whisked away, having stayed in Hong Kong little more than 12 hours and the whole circus of grand British officials quickly moved on.