‘One bullet, two bodies’: a Rohingya’s escape, from Myanmar to Malaysian madrassa

Inspired by his past, a determined refugee running a school in a Selangor suburb gives children displaced by violence the chance for a better life

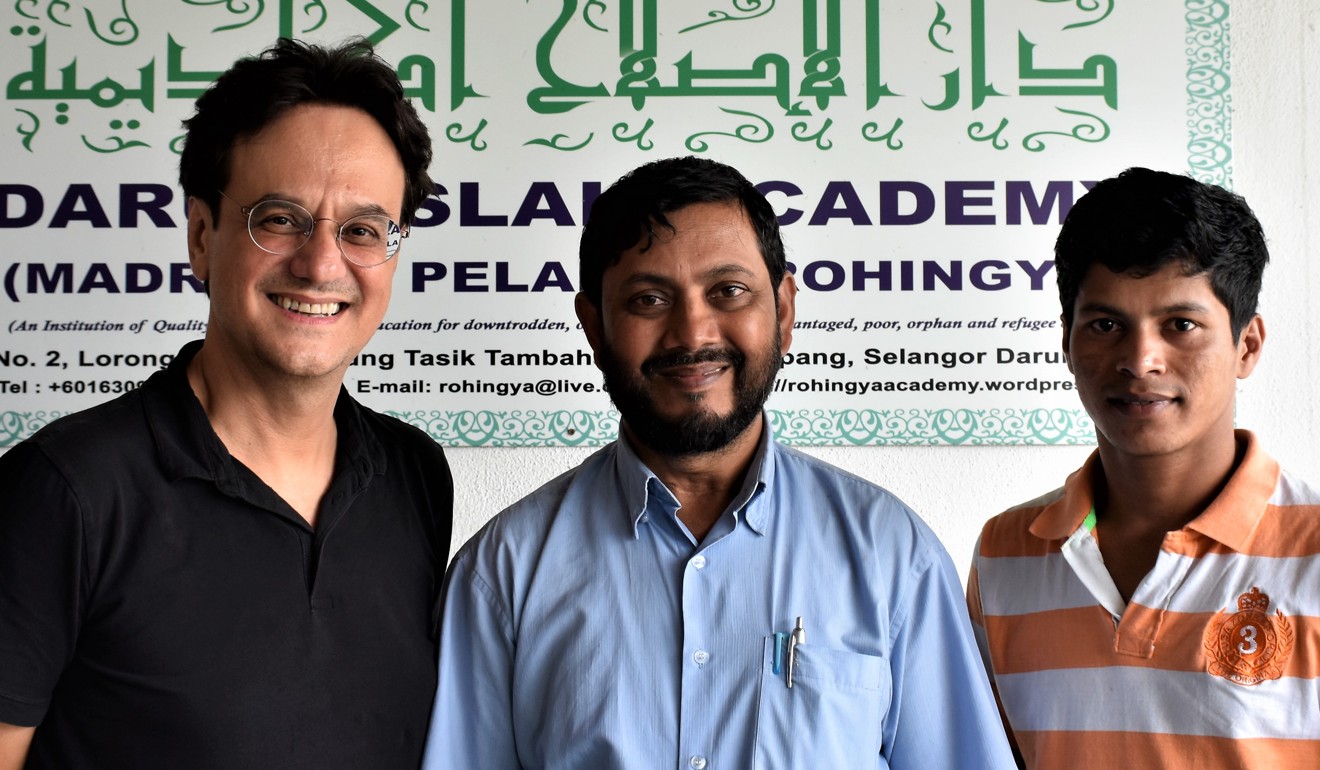

Sadek Ali Hassan is a 44-year-old teacher living in Malaysia. He is also a Rohingya. Sadek has spent over a quarter of a century living outside his homeland. As I meet him in the small, ramshackle madrassa he runs for the children from his community in the Selangor suburb of Ampang, he’s at first reluctant to talk about his past.

As we chat, however, the memories of his village –Taung Pyo Let Yar, close to the Bangladesh-Myanmar border in the state of Rakhine – come flooding back.

“My family were landlords. My father alone had over 16 acres of land. We grew rice, chillies, cabbages, potatoes, tomatoes, tobacco, brinjal, pumpkins – but the most profitable crops were betel leaf and nut. There was so much fruit – bananas, coconut and jackfruit. We even had fish ponds.”

“My life was perfect. I went to school and in the evening, I would play with the neighbourhood kids. I loved school. We were taught in Burmese but we’d also learn English. Every morning we’d go the mosque for religious classes then we’d move to the government schools after which we’d return to the mosque again. English was my favourite subject.”

The idyll was not to last. In 1988 as pro-democracy demonstrations swept Myanmar, his corner of Rakhine state joined in the protests. Within a year, new border security forces appeared in his village. Garrisoned nearby, they started picking up locals and forcing them to join work gangs.

“I was a student leader, an activist, so I was detained regularly. One of the favourite punishments was the ‘motorbike’ – you had to stand for two to three hours as if you were sitting on an imaginary bike with your legs bent and your arms outstretched, whilst making the noise of an engine. If I stood up, I was kicked. If I stopped humming, I was slapped. If I put down my arms, I was punched.”

As the situation deteriorated, Sadek realised he would have to leave Myanmar. “I stayed there for years, even after all the beatings. But one day, I snapped. I was at a Ramadan bazaar. A man next to me ordered a bagula (fried flour cake) for iftar. Immediately after, a Buddhist man came and just snatched the cake. They started fighting each other. It was a Muslim village and of course the people started helping the Muslim. Not long after, the Buddhist ran to a nearby security outpost.”

“It wasn’t long before other security guards came. They opened fire into the crowd. I saw a bullet that went through a man’s waist, and hit another man in the chest. Two people, one bullet. I ran away the next day. That day was January 9, 1992, on my birthday”.

On that fateful day, after having carefully gathered together money from sale of farm produce, he crossed the border to Bangladesh with seven friends.

‘There is no ethnic cleansing. There is no genocide’: Myanmar’s ambassador to UN repeats denials of campaign against Rohingya

“I was scared, but I felt I was going to a new life,” he said.

“Back then we were among the first of the Rohingya to arrive in Bangladesh. There were no camps in those days. After I left, the military authorities came for my father. They detained him for a week after which he had to present himself every day with little bribes – a chicken, some alcohol. Within a month he knew he would have to leave as well. There was no way he could sustain the stream of ‘gifts’.”

Sadek is a practical man. Having spent countless years on the road, organising and writing about Rohingya activities and shuttling between Bangladesh, India and Thailand, he finally arrived in Malaysia in 2006. His school, Darul Eslah Academy, with its 103 pupils is a bold assertion of hope and determination for a people who are fast becoming the Palestinians of the Southeast Asia.

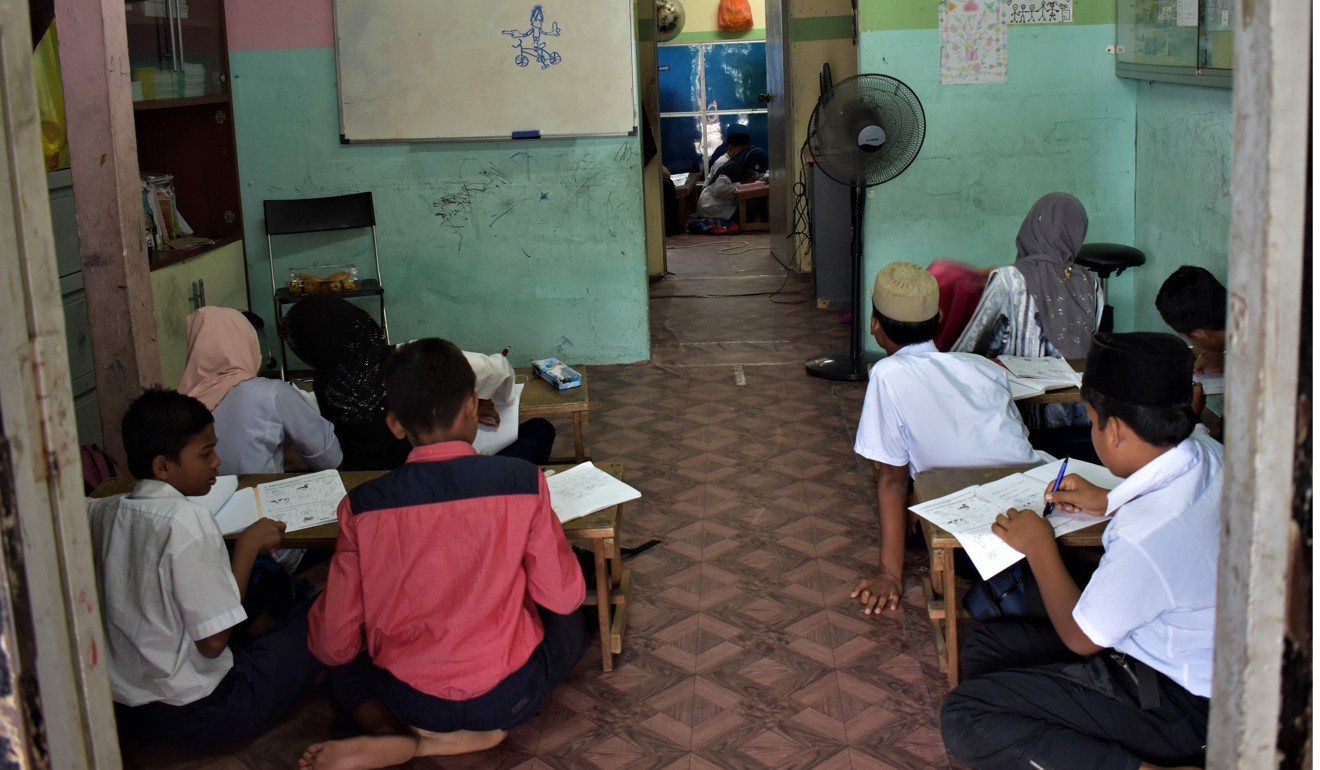

“There are now well over 5,000 Rohingya in the Ampang. Many of the children have missed out on their education. At least here they can learn to read and write. In the mornings, they follow the Malaysian syllabus then they have religious classes in the afternoon.”

“I want them to have a future. I have a direct interest in all of this because I have four small children of my own. I mustn’t give up though there are times when it’s all too much. We have children who could become engineers, doctors or judges but they need a home.

“I am grateful for the Malaysian government for providing us with a place to live. But I feel like I am in an open prison. I can eat and sleep here. I can live, but I can’t go anywhere. We are like prisoners with an endless sentence. We don’t know how long we will have to live like this – two years, 10 years, 20 years? We don’t know.

“I still hope to return one day. When? I don’t know. The violence is getting worse and the number of refugees only increasing. This is out of my hands. This is in God’s hands.”

Rent, food and other costs for the school come to 8,000 Malaysian ringgit (HK$14,800) a month, but Sadek is scraping by with only 4,000 ringgit. The school strains to meet the demand – some classes are conducted in the kitchen due to a lack of space.

Trapped on beaches or hiding in the jungle: though numbers are falling, latest Rohingya refugees say thousands are still stranded

In the wake of the tahfiz school fire in Malaysia that claimed 23 lives, I can’t help but be concerned over the risks present in this overcrowded environment. While this madrassa is not a residential school like the one in the incident, the danger still looms.

“Sometimes, individuals give donations. But we need something sustainable. I haven’t paid my teachers in months. Even him,” he said, pointing to his nephew.

“If not for them working without pay, the school would have closed years ago.”

When I asked how he remained so hopeful, he replied: “If I don’t give them education, they will have nothing. We must dream of going home. I just want to give them a ray of hope, so at least they can write their own story. Religiously, I want them to at least understand halal and haram. If I don’t take this responsibility, the time will come where I will face the question: What did you do for humanity?”

Our conversation was interrupted as a crowd of children stormed the room, tugging at Sadek’s shirt, vying for his attention. Some 2,000km from Rakhine, this school might be one of the few places left in the world that allow Rohingya children to simply be children.