Big Data politics? It’s an ancient trick, we’re just better at it (and China has more to come)

Efforts to get inside the minds of voters are as old as politics itself

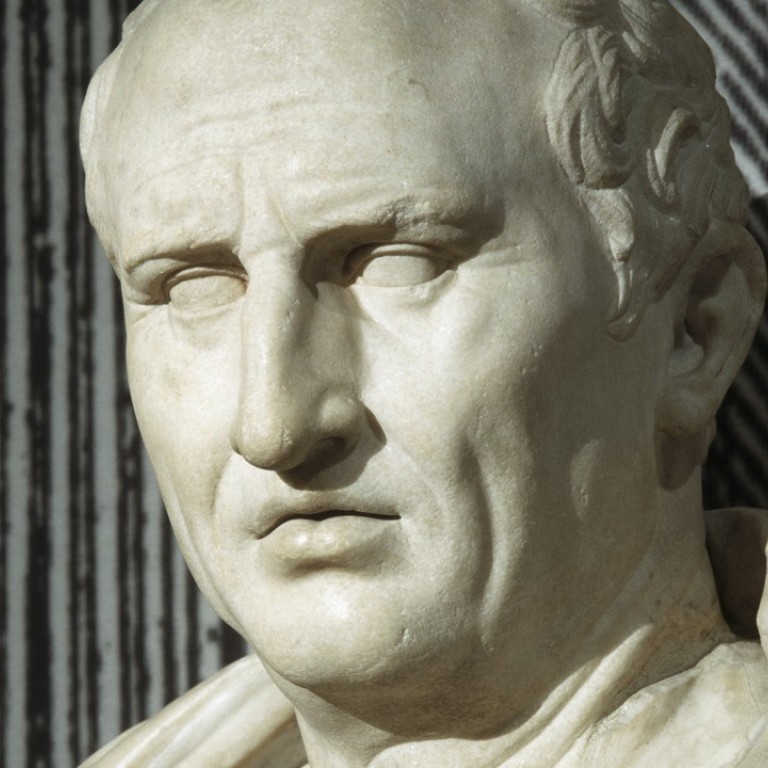

When Marcus Tullius Cicero ran for the office of consul in Rome in 64BC, he brought in his brother Quintus as his adviser. Quintus apparently offered wise counsel and, according to the texts, was not above dirty politics. It’s unlikely that Quintus was the first political consultant in history, but his approach has survived the ages: do anything and everything to win.

For those, like myself, who work in the world of politics, communications and polling, the digital revolution offers benefits aplenty. We can crunch more data, we do it much quicker and computational advancements can help us to identify patterns and trends, often from a multitude of data sources. We rely on these new tools for everything – new product testing, YouTube video development as well as political and government campaigns.

Artificial intelligence is on the rise in Southeast Asia, helping everyone from fashion designers to rice growers

Political campaigns are often fascinating to outsiders but like with many things, it’s not great to see how the sausage gets made. Campaigns have traditionally been labour intensive – banks of call centres filled with students and housewives, campaign volunteers pounding the pavements and hundreds of others in back rooms crunching data and offering advice on everything from the right message to the right neck tie. But this is changing. Everyone involved in a campaign today has at least one smart device and all information is being synched in real time. Live digital dashboards have replaced whiteboards and sharpies.

Psychographic profiling is a technique that aims to separate audiences not just by age, race, gender or income demographics but by other things they have in common. This can be behavioural (eg what they like to put in their shopping trolleys) or attitudinal (eg addiction to romcom films). Although psychographic profiling has been around for decades, consumer researchers employ it in increasingly sophisticated ways today to help them understand a consumer category better or to identify a gap in the marketplace. This has now reached a point where many companies are now relying on psychographic micro-targeting to tailor messages to smaller groups and even individuals.

Psychographic micro-targeting (of sorts) in politics was first popularised in the 1990s in the US with Clinton’s “soccer moms”. Indeed, Clinton’s pollster from that era, Mark Penn, later wrote a book called MicroTrends which largely foresaw the whole micro-targeting revolution in politics and communications.

Political leaders and governments across Asia are increasingly active in adopting new computational tools in their campaigns, no differently to what we are seeing elsewhere in the world. Indeed, the region is no stranger to political imports offering the latest election wizardry. Read the resume of any major American political consultant and they will likely list at least one Asian government or campaign they have been involved with.

Here’s how to beat fake data about the Chinese economy

Indeed, SCL Group, the company that Cambridge Analytica was borne out of, has had a presence in the region for nearly two decades. Its activities in Indonesia and elsewhere are well documented. Cambridge Analytica, it is reported, has also conducted work in Malaysia and India.

But while the CAs of the world roam the globe basking in their 15 minutes of glory, and hunting for willing benefactors, it is important to point out that home grown expertise is growing fast across Asia. There is no shortage of talent with technological prowess.

Following revelations that South Korea’s spy agency tried to influence the 2012 presidential election via the spread of fake news on social networks, the tables were turned in 2017. Although the winner, Moon Jae-in obviously benefited from a major scandal surrounding his predecessor, the employment of sophisticated online marketing, redolent of that used by major commercial brands, showed how groups of voters could be targeted effectively. For example, the clever reliance on more visual social media such as Instagram and KakaoStory rather than Facebook may have been a world first.

Political campaigning on social media in 2018 is now standard practice, even in emerging markets, but more sophisticated psychographic micro-targeting in Asia (as popularised by Cambridge Analytica) probably had its first real regional success in the 2014 mayoral campaign in Taipei which was won by ‘independent’ academic Ko Wen-je.

Ko was a technology true-believer and entrusted his campaign to young data crunchers who, among other things, built crawler bots for Facebook and gathered information on individual users. The Computational Propaganda Project at Oxford University interviewed people close to the campaign who claimed the data collected allowed them to craft messages for more than 10 psychographic groupings in the days leading up to the election. For them, it was all about precision. Apparently, they were able to gather data on 11-14 million Taiwanese Facebook users, or at least half the island’s population.

This enabled Ko to tap into concerns among young voters with respect to pressure from China. By highlighting the issues faced by the Occupy Movement in Hong Kong, he successfully got young voters to focus squarely on what they thought Taiwan should look like in the future. Given the climate at the time, he was able to tap into disaffection and get voters to choose between fear and hope. Did it work? Well, Ko won in a landslide.

So what do all these new techniques amount to? Are politicians now able to see our every action (‘Good morning, Alexa)? Well, the truth is they have always wanted to and are now better able to peek behind our blinds. As to whether it changes the world of elections, that’s more debatable.

The Machines are Coming: China’s role in the future of artificial intelligence

Consumers (and voters) often move on very quickly. This is becoming even more pronounced in an age of short memory span. Just as people learned to adjust and process the various tropes of traditional media (television, print, talk back radio, etc), it is likely that most will eventually adjust to the current breathlessness we see on social media agitation. Over time, most people will become more accustomed to the patterns and plays by various parties on social media and a lot of the material that creates sparks now will lose its heat. And the marketers will try to find new ways to influence minds.

The reality is that voter targeting and profiling has continued to advance for decades and the emerging industry practices and techniques that have now been shared with a global public will continue to get even more sophisticated as technology progresses and will be shaped to fit new consumer platforms that emerge. A key question is to what extent politicians will be prepared to pass laws that restrict their own opportunities to know more about voters. It’s often hard to kill the goose that lays the golden egg.

Arguably, it is also important not to overlook where the next generation of tools are being developed, with and without government oversight. Experts are well aware of the progress being made in China and Russia in coming up with even more sophisticated tools. Israel too. Suddenly, it’s a global industry in the making.

Cambridge Analytica, for a while at least, rode their luck. They undoubtedly did a great job packaging and marketing ideas and approaches which were already being adapted widely. And then it all went to their heads. The firm’s biggest mistake, ultimately, may have been attaching itself so closely to Trump’s electoral success.

As with many others who have made the mistake of using Trump to advance their own careers, they just may have flown a little too close to the sun. The smart ones won’t make the same mistake. ■

David Black is owner and managing director of Singapore based polling company, Blackbox Research