Is Indonesia’s Reformasi a success, 20 years after Suharto?

Indonesia has come far on its road to democracy. Yet the dictator’s generals retain influence, pockets of extremism fester, freedoms are being whittled away and a corrupt judiciary holds court.

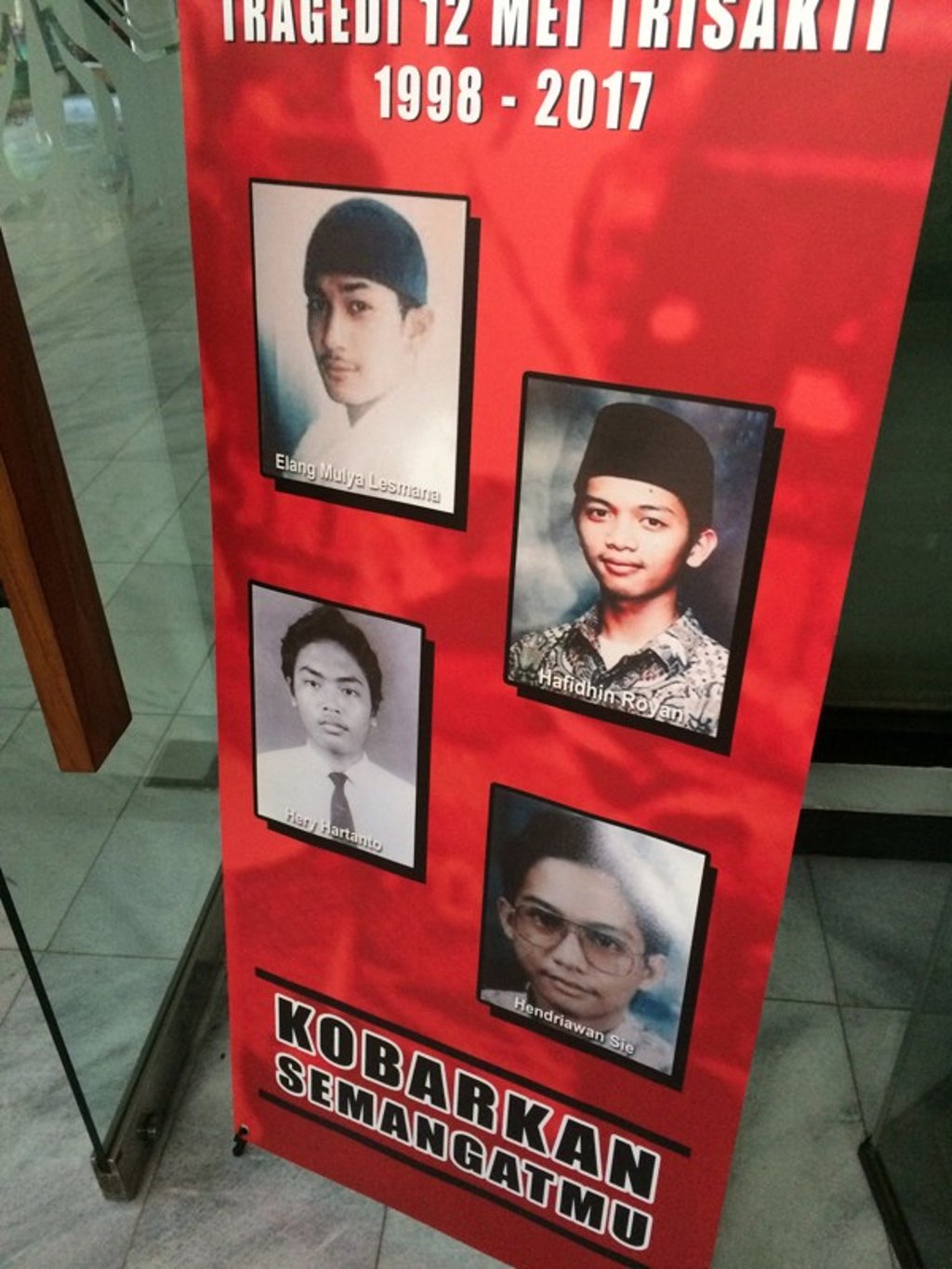

Usman Said surveys the stainless steel plaques bearing the names of his fallen classmates at Trisakti University in Jakarta. Twenty years ago this week soldiers gunned them down amid escalating protests that within days would topple the dictator Suharto.

Snipers that day held off ambulances, leaving the young men in their early 20s to bleed to death. Said, who now heads Amnesty International in Jakarta, takes some solace that their deaths weren’t in vain. “We have freedom of assembly and speech and the press,” Usman says. “These freedoms are what we fought for.”

By any objective measure Indonesia’s democratic transition, or Reformasi, has been a success. Power has transferred peacefully between five presidents – two of them directly elected. Simmering conflicts in Aceh and elsewhere were eventually quelled with devolved powers and autonomy.

Indonesia was supposed to be embracing freedom. What happened?

“Compared with where we started in 1998, it is significant that power is being alternated between administrations through electoral means,” says Philips Vermonte, a researcher at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Jakarta.