Indonesian Chinese still face discrimination 20 years after Reformasi

The fall of Suharto was marked by anti-Chinese riots that killed 1,000. Twenty years on, violent repression is in the past, yet resentment of a largely Christian community in a largely Muslim country remains

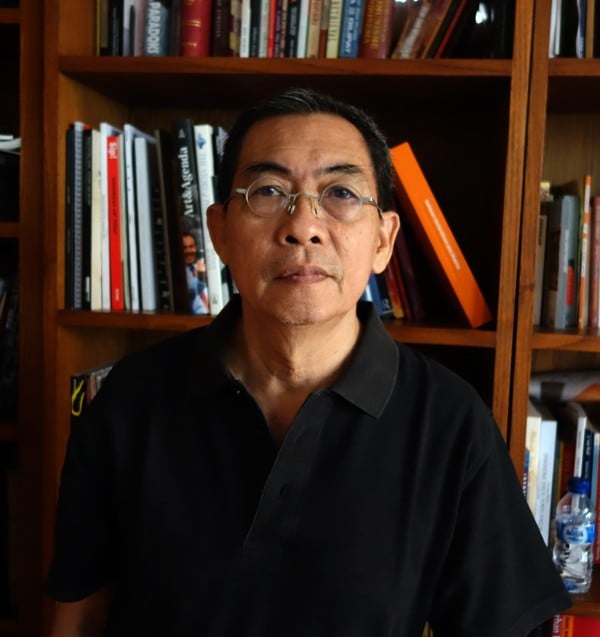

When Francis Xavier Harsono applied for his first passport in 1992 he was brimming with anticipation for his first trip overseas. Back then, things were looking up for Harsono, one of Indonesia’s first contemporary artists. He had been making a name for himself with work that subtly criticised the Suharto regime and an artist-in-residency programme in Adelaide, Australia, awaited him.

But then the bureaucrats struck. The passport office forced Harsono, an Indonesian of Chinese descent, to return to his local government office for paperwork proving his nationality. Adding insult to injury, he also had to pay a bribe of US$200 – a colossal sum at a time when a plate of fried rice from a street vendor cost a few cents. Harsono managed to satisfy the officials and went to Adelaide, but the incident stung.

“I was very angry. But I couldn’t do anything, I had to pay,” says Harsono, who goes by the name FX Harsono in his art work.

Fast-forward two decades and the blatant discrimination that marked the era of the dictator Suharto is a thing of the past. Bans on Chinese culture and language during that era were lifted in 2001. Lunar New Year is now an official holiday.

Could anti-Chinese violence flare again in Indonesia?

But resentment of the perceived wealth and influence of ethnic Chinese still bubbles under the surface, and many among the country’s 3 million ethnic Chinese fear a new chapter of intolerance may be at hand. Incidents such as the imprisonment of Jakarta Governor Basuki Purnama, a Christian of Chinese descent better known as Ahok, on blasphemy charges and recent attacks on Christians in Surabaya have them worried.

Last week three families allegedly linked to an extremist group that had pledged loyalty to Islamic State carried out suicide bomb attacks on churches and police in Indonesia’s second largest city, killing more than dozen.

“After Ahok and the attacks in Surabaya, of course, I feel very nervous about the future of Indonesia,” says Sylvie Tanaga, who handles media relations with the non-profit think tank Urban and Regional Development Institute in Jakarta.

She has reason to be nervous. Twenty years ago this month – when Tanaga was 11 – she heard the word “rape” for the first time as anti-Chinese riots fanned out across the country targeting Chinese women. The riots were sparked by rumours that ethnic Chinese were hoarding rice. At least 1,000 people were killed in the resulting violence.

Why are ethnic Chinese still being denied land in Indonesia?

Those horrors may be in the past, but suspicions over the economic success of ethnic Chinese – many of whom are Christian in a country that is 90 per cent Muslim – linger.

Of the top 10 richest Indonesians, nine are ethnic Chinese, according to Forbes. And rich and powerful ethnic Chinese hold sway in Indonesian politics, just not from elected office.

The government of President Joko Widodo looks to Harvard-educated Tom Lembong, chairman of the Investment Coordinating Board, to woo foreign capital. Back in 2015 when the Jakarta Asian Games was years behind schedule, Widodo turned to Erick Thohir – the brother of billionaire Garibaldi Thohir – to deliver the event. And when Widodo needed to sell his US$300 billion tax amnesty he got help from Mochtar Riady, Indonesia’s ninth richest man, who told the world that Indonesia was a safe place to park your money and that rich people needed to pay their taxes.

But this does not fully explain the tension – after all, most ethnic Chinese are as far removed from the Forbes list as their fellow Indonesians. Roy Thaniago, director of media advocacy group Remotivi, instead blames persistent discrimination on the Indonesia education system, which emphasis the Chinese were relatively recent arrivals. Thaniago, who last year wrapped up a master’s thesis on Chinese discrimination in Indonesia at Sweden’s Lund University, says Chinese have been a frequent victim of abuse over the 500 years they have lived in Indonesia. In 1740 more than 10,000 were slaughtered in anti-Chinese pogroms in the Dutch colonial capital of Batavia, the precursor to modern Jakarta.

Today violent repression may be gone but race remains a potent force in Indonesian politics. At his swearing in ceremony last October, Ahok’s successor, Anies Baswedan, called on the ethnic Malay majority – known as pribumi – to become “masters of their own house”.

For Thaniago, and others, bullying, discrimination and humiliation are common. As a child he recalls hiding lunch money in his shoes so that when bullies caught him and searched his pockets they were less likely to find it.

Even now, aged 32, there are bitter encounters. Three weeks ago while eating at a street stall a busker berated him because Thaniago wouldn’t give him money. None of the other customers did either. “He needed a target,” Thaniago says of the busker. “And it was me.”

The key is education. Civics is a mandatory class in Indonesian schools. The classes are an opportunity to emphasise tolerance and challenge the “us versus them” mentality that goes hand in hand with nationalism, he says.

Why Chinese-Indonesians don’t have to hide any longer

“Nationalism here tends to be anti-communist, anti-Chinese, anti-LGBT,” he says, using the acronym for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered people.

“We need to be more relaxed.”

For Harsono, art is the way to bring Indonesians together.

Earlier this year a video installation that simulated him painting his Chinese name in the rain was on display in Times Square in New York. That piece symbolised letting go of the past.

Work from his 2002 series “Point of Pain” is showing this month at the Frieze New York art show. The art features butterflies pinned as a taxidermist might onto a human face. It sounds gruesome but the end product emphasises life’s fragility and pain when we aren’t free, he says.

“Art is a strategy. We can use art to learn how to criticise,” Harsono says. “We can see people and learn to love each other.” ■