Will new Malaysia have same old racial divide? Ethnic Chinese Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng seeks post-election unity

In a racialised political system where the Malay majority has always felt threatened by the Chinese minority, the transfer of the finance portfolio to Lim is remarkable. But can the country come together to move forward?

When Lim Guan Eng walks into his office in Putrajaya – with its oak shelves barren of books and glass cabinets glaringly empty – a group stands up to extend him deferential greetings. All the women are clad in hijab and almost all the men are Malay, the majority race of Malaysia.

Lim, 57, is Malaysia’s new finance minister. It is a post that has been entrusted to an ethnic Chinese Malaysian for the first time in 44 years. Lim takes over from former premier Najib Razak who held the finance portfolio before a historic election pushed him from the centre of power and into the middle of a multibillion-dollar corruption investigation.

Anwar backs Mahathir’s review of Chinese deals – but not to annoy Beijing

In a highly racialised political system where the Malay majority has always felt threatened by the Chinese minority’s disproportionate economic power, the transfer of Najib’s powerful finance portfolio to Lim is in itself remarkable. But then there is very little that hasn’t been, in the days and weeks following the May 9 election that saw the only ruling alliance independent Malaysia has ever known toppled after 61 years in power.

“We can differ strongly and yet we can work together as one team and that’s the most important element. If this country is to move forward, we got to act in concert, we have to move together as one team. One person cannot save the country, we need every single one of our 31 million Malaysians to help us save Malaysia,” Lim says.

Malays and other indigenous people are accorded special protections in the country’s constitution, and Islam, the religion of almost all Malays, is the country’s official religion. While these basic principles, collectively called bumiputra (“sons of the soil”) policies, are widely accepted as non-negotiable, there has been growing unhappiness over how they have come to be applied in ways that have turned ethnic and religious minorities into second-class citizens.

KL-Singapore high-speed rail link hit buffers over US$25 billion bill: Malaysian Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng

The dominant party in the previous ruling alliance, the United Malays National Organisation (Umno), was centred on “Ketuanan Melayu” or Malay supremacy. The “bumiputra policy” of affirmative action became an excuse to give the Malay rich unquestioned access to state largesse, at the expense of poor Chinese and Indians. To compete against the opposition Islamic Party of Malaysia (PAS), Umno also adopted increasingly hardline Muslim rhetoric.

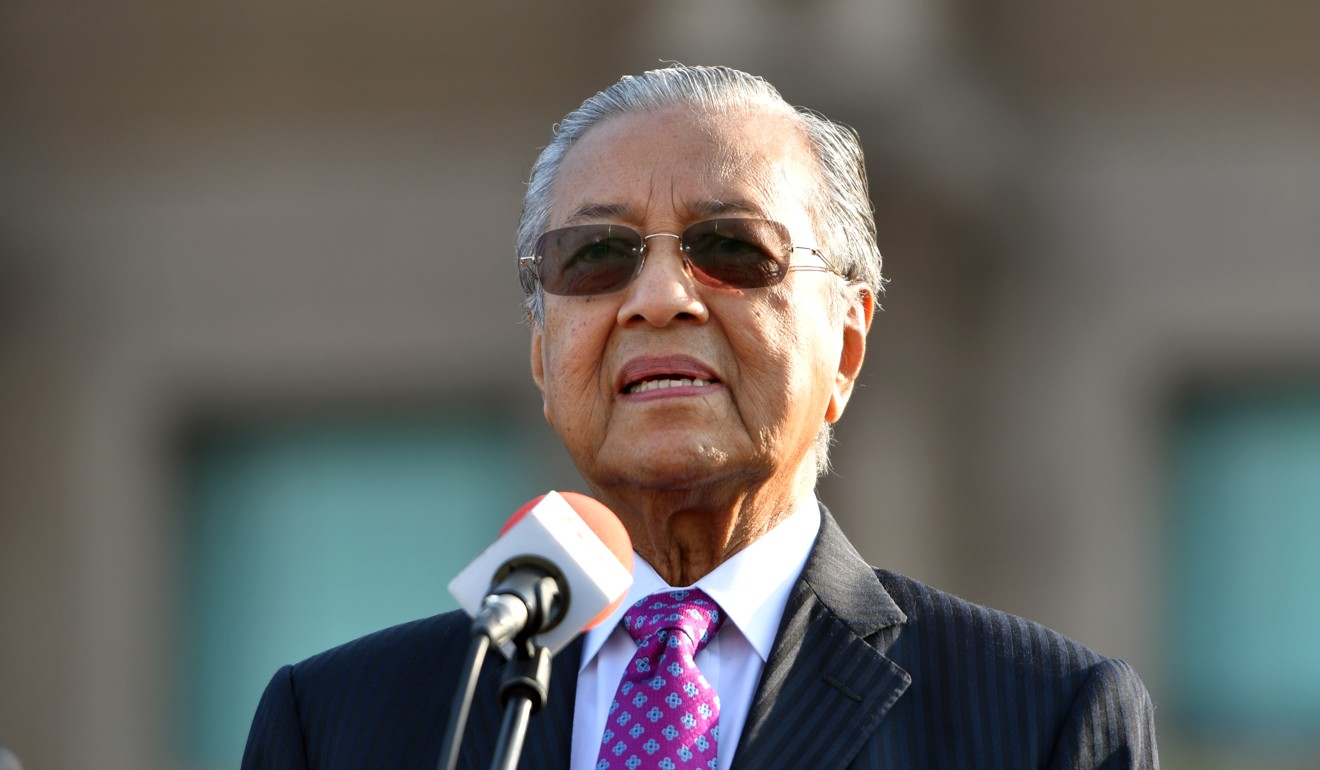

Pakatan Harapan, the new ruling coalition, has maintained certain characteristics of the old race-based regime so as to win over support of the majority Malays. It is helmed by prime minister Mahathir Mohamad, who as a former Umno leader was a fierce champion of the Malays. His party, Bersatu, is a bumiputra-based party. Its full name, the Malaysian United Indigenous Party, makes that clear.

Malaysian finance chief: ties with China, Singapore not derailed by loss of projects

But the biggest party in the coalition is Parti Keadilan Rakyat (People’s Justice Party), the avowedly multi-ethnic party. Its founder, Anwar Ibrahim, is expected to take over from Mahathir as prime minister in two years. Although also an Umno veteran, Anwar’s long-time pledges to replace the race-based policies with need-based help, as well as his democratic reform agenda, have made him the main icon among Malaysians wanting change. At the same time, his Islamic credentials are strong enough to have made Pakatan Harapan a magnet even for defectors from PAS, in the form of the Islamic Party, Amanah.

On the whole, the changes have been radical enough to sweep most Malaysians, whether in the country or in its far-flung diaspora, with an unfamiliar hope that borders on euphoria. Still, detractors wonder if Mahathir the one-time dictator can really change his style, and if Pakatan Harapan is really just old wine in a new bottle.

As leader of the opposition Democratic Action Party, Lim has spent most of his political career opposing Mahathir. Mahathir even sent Lim to prison not once, but twice, during security operations in the 1980s when he was detained without trial under the draconian Internal Security Act (ISA) and then in the 1990s under the Sedition Act. Lim’s father, founding DAP secretary general Lim Kit Siang, was also detained by Mahathir under the ISA.

He now finds himself in the situation, which he would have found bizarre just a year ago, of defending his old nemesis.

He does not dismiss the cynics outright but responds this way: “But many have said that Tun Dr Mahathir version 2.0 is much better than version 1.0 even though he is 92 years old and I must say I was quite surprised by Tun Dr Mahathir version 2.0.

“He has shown his commitment to the manifesto. He wanted to be education minister but when it was pointed out to him that the manifesto doesn’t permit the PM to hold any ministerial post, he immediately gave it up … do you think Tun Dr Mahathir version 1.0 would have done so? So, I think this version 2.0 is much better. It is suited for the current situation where Malaysia needs everyone to come together to save our country. He is the right person at the right time to get the job done.”

Asked what working with his former jailer whom he repeatedly called dictator and authoritarian is like, Lim laughs out loud and says Mahathir is now fond of reminding them that, “I am no longer the dictator, you are dictating”.

Malaysian finance minister Lim Guan Eng’s ‘belt-tightening’ plan for 1 trillion-ringgit debt

Lim also admits that it was the excesses and “daylight robbery” of Najib and the previous administration that solidified the opposition ranks into a united bloc.

Previous attempts to unite the opposition failed, mainly due to differences between Lim’s own DAP, which is mainly Chinese, and the Muslim party, PAS. In 2008, after achieving a breakthrough by reducing Barisan’s parliamentary majority to below the two-thirds threshold – preventing it from rubber stamping key legislation – and collecting five federal state governments, infighting derailed the opposition coalition.

In 2013, the opposition tide slowed. The old regime’s loyalists have been quick to mock the Pakatan Harapan parties’ marriage of convenience as similarly doomed to fail.

“We need to be more cohesive,” Lim candidly replies when asked to identify the coalition’s main challenge. The biggest danger for Pakatan is to be “dragged down by petty issues” that could sow the seeds of division again, he says.

This time around, Lim and others are more acutely aware of the need to stay tight on one ship to ride on the opportunity to make history together. The new leadership isn’t just drawn from ideologically distinct parties, it is burdened with plenty of personal baggage. In addition to Lim and his father being jailed, there is Anwar Ibrahim, accused of sodomy and put away in prison by Mahathir for more than five years. Another former opponent, Mohamed Sabu, was also detained twice after being accused of being involved in extremist movements. In the new government, Mohamed Sabu, more affectionately called Mat Sabu, is the defence minister.

They might make strange bedfellows but Lim believes that their internal discussions – “frank, animated, constructive and productive” – had strengthened their bonds and that they could “still walk out as friends, as allies”.

The mainstream media, much of which is still controlled by pro-Barisan owners, is one bellwether of change.

Utusan Malaysia, a pro-Umno newspaper that feeds chauvinist trolls, is famed for a 2013 election front page headline, “Apa lagi Cina mahu?” or “What else do the Chinese want?” chastising the Chinese for not being grateful to the ruling coalition.

Lim Kit Siang and Lim Guan Eng were favourite targets of scaremongering. But since May 9, Utusan’s coverage of them has been more moderate. Reports on Lim urging unity among the races have received prominent play.

China expects ‘next level’ relations with Malaysia as Mahathir enlists Robert Kuok in diplomatic push

The appointment of Lim as finance minister has been relatively smooth, says MP Tony Pua, who is Lim’s political secretary. “If you had talked about it before the election, it would have been a massive hoo-ha in all mainstream newspapers, a controversy that might even have incapacitated our campaign; but post-campaign, everyone seems to have realised that hey, it’s a new Malaysia.”

Most Malaysians today seem to recognise racial issues as a “manufactured agenda” of politicians trying to distract from deeper problems such as economic inequality and elite excesses, Pua says. “The race angle doesn’t work.”

But Utusan headlines suggest that ethnic nationalists aren’t giving up without a fight. One hot-button issue is UiTM, the public university reserved for bumiputras. Admitting needy non-bumiputra students would be in keeping with the “new Malaysia”, but a Utusan headline this week proclaimed, “Defend UiTM”. The story quoted a former vice-chancellor declaring that opening it up to all citizens amounted to an attack on Malays.

Such a move would require a major expenditure of political capital – which may be one reason why Mahathir volunteered to take on the education portfolio.

Malaysia’s billion-dollar question: where did 1MDB money go? New Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng says money trail will reveal all

Lim says that whether losses from the 1MDB scandal could be recovered by the newly elected government was “a billion-dollar question”, but he was determined to track down the culprits.

The soaring debt has forced the new government to shelve major infrastructure projects with foreign partners, leaving Singapore and China as the most severely affected. But that does not mean close bilateral ties between the two nations and Malaysia should be derailed, Lim says.

“I am sure they would want to see their neighbours prosper.”

June 1 also marked the suspension of the unpopular 6 per cent goods and services tax that Najib introduced in 2015. Malaysia can expect such sweeteners to help citizens swallow the bitter medicine that economists say is bound to come.

Lim acknowledges that Mahathir would have to make tough decisions, including some that will upset his coalition partners. “If you make decisions after discussions are held, this is part of democracy. If consultation, dissension are permitted, then this is not a dictator but a democratic leader.”

On his own path, he says: “I never thought I would become chief minister of Penang. I still could not believe it. And now, as finance minister, I never ever imagined this could happen.”