Asian Angle | Why Singapore won’t be repeating Malaysia’s political dramas any time soon

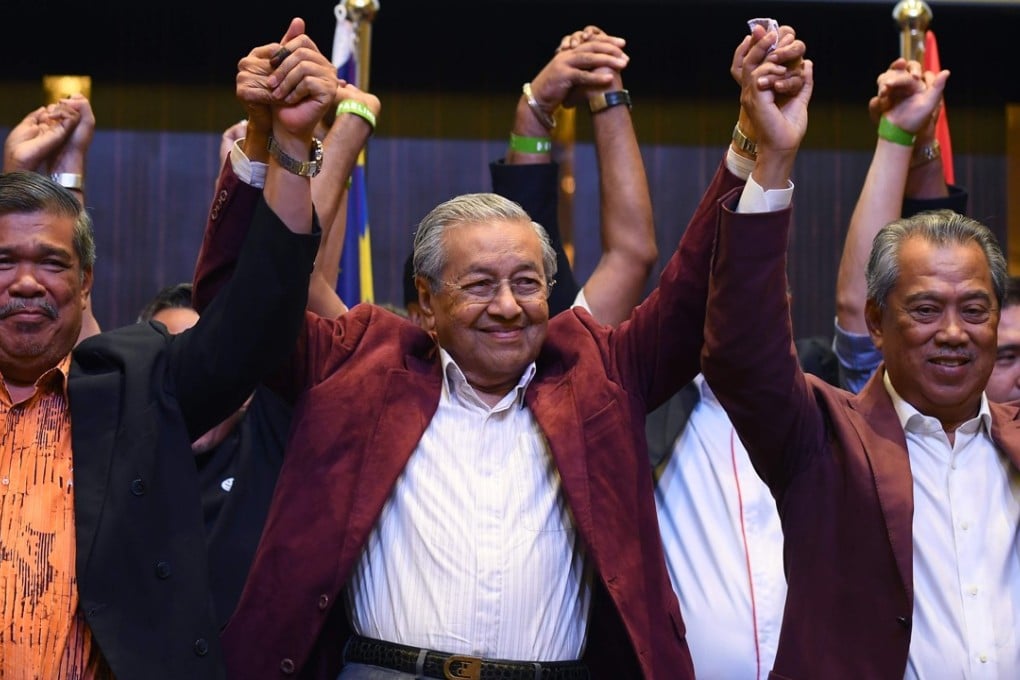

As a political underdog, new Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad had a legacy, a cause and a corrupt adversary to fight against. Aside from higher costs of living, the Lion City has little to inspire a change at the top

In May, soon after the surprise victory of his Pakatan Harapan (PH) alliance in elections, he quipped that Singaporeans “must be tired of having the same government, the same party since independence”, a clear reference to the republic’s ruling People’s Action Party’s (PAP) almost six-decade monopoly on power.

Understandably, the 93-year-old’s pronouncements on the city state since returning to power have drawn a lot of attention.

Intrigued by the possibility of change in Singapore, Team Ceritalah travelled across the causeway to see what local residents thought of Malaysia’s historic election and how – if at all – it would impact them.