Has Malaysia moved past race-based politics? By-election will give first clue

An upcoming vote in Selangor will be watched closely to see if newly elected Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s ruling party has to move further away from its progressive agenda to hold ground

Malaysia’s first by-election since the May 9 polls, which saw the Barisan Nasional coalition cede power after more than six decades at the helm, will be seen as a litmus test for race-based politics and a measure of how much support the government has from the Malay electorate, which makes up 62 per cent of voters.

After the general election, race-based parties such as the Malaysian Chinese Association and the Malaysian Indian Congress became politically irrelevant, winning only three parliamentary seats between them. But if Pakatan Harapan loses the Sungai Kandis by-election in Selangor, its leaders may see the need to move to the right to hold ground, or potentially court the defection of United Malays National Organisation (Umno) parliamentarians. Umno, having nothing to lose, can play the race card to the hilt. A Pakatan Harapan defeat could carry far greater national implications than that of the seat’s value in Selangor itself.

In Mahathir’s Malaysia, no gay rights and no free speech

Sungai Kandis is one of Selangor’s 56 state seats, of which Pakatan Harapan won 51 during the elections. There are two more by-elections pending following the deaths of two assemblymen.

Pakatan Harapan’s candidate Mohd Zawawi Ahmad Mughni will be running in the August 4 polls in Selangor on a Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) ticket – Anwar Ibrahim’s party. The constituency’s incumbent, Mat Shuhaimi Shafiei, was also from PKR, winning the seat with a 12,480 vote majority in the May general elections before succumbing to cancer in July.

Meanwhile, Umno, now headed by former Home Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, is fielding Supreme Council member Lokman Noor Adam. Lokman, a former PKR member, has accused his old party of nepotism and cronyism. A third candidate, Murthy Krishmasamy, is running as an independent.

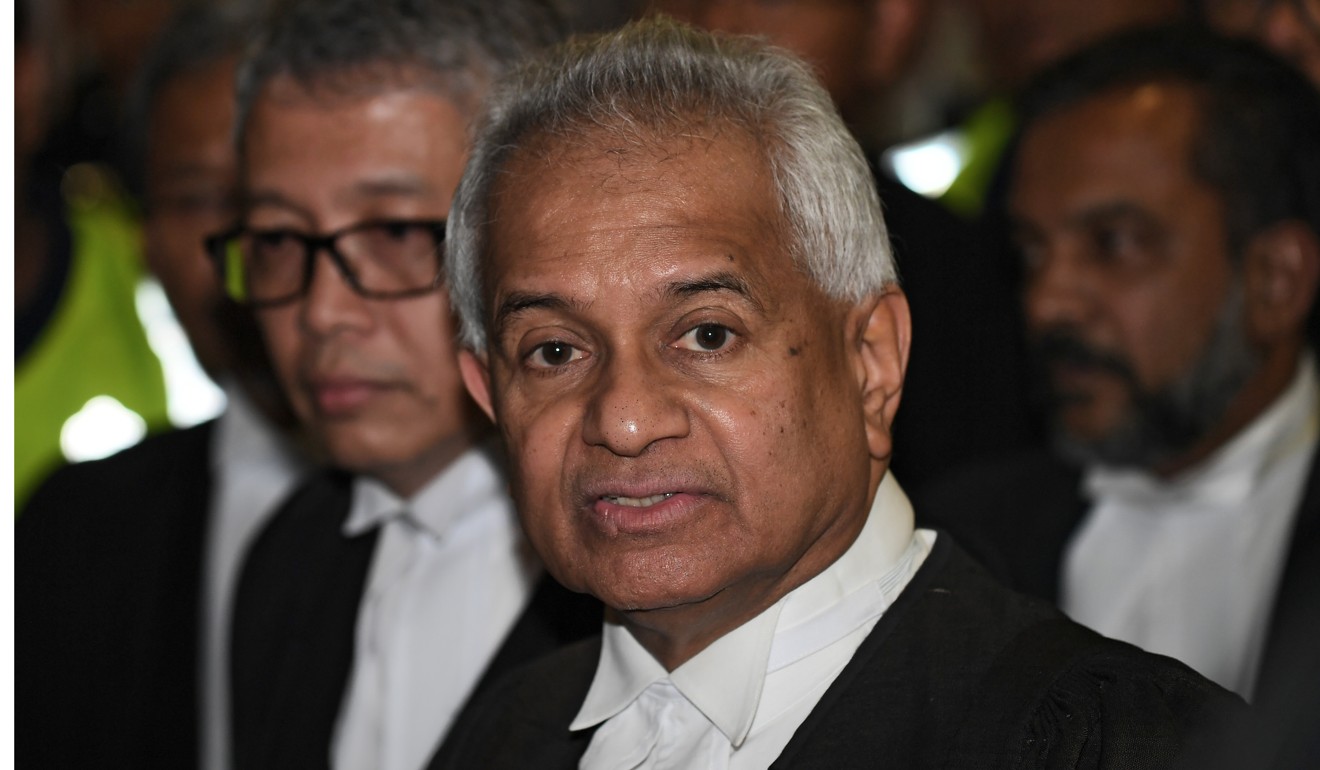

Criticisms of the new government include the number of non-Malays appointed to high-ranking government positions, such as the attorney general’s role, which was given to ethnic Indian Tommy Thomas. The idea that the Pakatan Harapan government is not backed by the Malays is being pushed once again in this by-election, a move that analyst James Chin believes will spell out the strategy for the opposition going forward.

“If this works, playing with Malay supremacy and Islam, then it will be rolled out for every subsequent by-election. If Pakatan Harapan cannot hold a Malay area, it may be forced to move to the right,” he said.

During its time as an opposition coalition, Pakatan Harapan’s vote bank was largely considered to be urban voters and the ethnic Chinese and Indian communities. However, the recent national polls saw what has been referred to as the “Malay tsunami”. Malay voters turned away from the incumbent Barisan Nasional in favour of a comparatively progressive opposition that also promised to tackle cost-of-living woes.

Najib in court: what to expect from Malaysia’s biggest trial

Post-election, independent pollster Merdeka Centre reported that Pakatan Harapan’s Malay support base was still only between 25 per cent to 30 per cent, with the remaining Malay voters split between Barisan (35 per cent to 40 per cent) and PAS (30 per cent to 33 per cent).

The report also stated that Pakatan Harapan had 95 per cent of the Chinese vote, and 60 per cent to 70 per cent of the Indian vote, reinforcing the perception that it was the choice for urban and non-Malay voters.

Chin said that in the May polls, the Malay vote was split three ways – Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS), Umno, and Pakatan Harapan. The risk now, he believes, is that Umno and PAS have formed a “devil’s pact”.

Is Malaysia ready to move on from Najib’s one-man show?

“PAS is in a situation where it is locked in the original states it was popular in back in the 1950s and can’t seem to break out. Joining Umno and playing the race card is an opportunity for them to do so.”

The Sungai Kandis by-election offers the electorate the same choice it faced during the general elections: an arguably more progressive Malaysia, or a “more hard-line “Malay supremacy” Malaysia.

“The only difference is that now Pakatan is in government and Umno is opposition,” with other component parties absent, said Chin, who is director of the Asia Institute at the University of Tasmania.

Sources on the ground, however, believe that the opposition’s choice of candidate was their first mistake.

“Lokman is former PKR, a multiracial party. By virtue of that alone, he is hardly the benchmark for Malay supremacy or leadership. All it tells people is that Umno is not changing its tune and only has a few cards to play.”

And if Umno believes that the race card will garner them a sure win, then it may be dismally mistaken. The Pakatan Harapan candidate, a religious teacher fondly referred to as “Ustaz Zawawi”, is hardly the progressive, pro-LGBT urbanite that Umno demonises as a threat to traditional Malay values. His working-class background and history as a member of ABIM (the Muslim Youth Movement of Malaysia) paint him as quite the opposite. Zawawi was described by some voters as “very Malay” and “down-to-earth”.

Ignoring 1MDB scandal ‘caused Umno’s downfall in Malaysia’

“That’s the image Pakatan is putting forward,” said a party worker. “He is the kind of man that Umno would never put forward – salt of the earth, a local candidate. They have no dirt on him. But we are also emphasising that PKR is multiracial. We can field a Malay candidate that will look after everyone.”

Pakatan Harapan intends to use the last stretch before the Aug 4 polls to push for voter turnout. Following a redelineation exercise in the first half of the year, Sungai Kandis, formerly known as Sri Andalas, was just one of several constituencies that was slammed as being an “unbalanced electoral zone”.

“This constituency was one of the main reasons why Selangor protested the redelineation exercise in court. It was terribly broken up by the Electoral Commission. In a house with five residents, three would vote in one constituency and two in another. That, coupled with how some lower-income households are unaware there’s a by-election, could hurt Pakatan Harapan.”

Pakatan Harapan is largely confident of Indian and Chinese support in Sungai Kandis, who make up 16 per cent and 12 per cent of the votes, respectively.

Political scientist Wong Chin Huat, who is attached to Penang state government think-tank Penang Institute, believes that any significant drop in the Malay vote could be interpreted as a “boost for the covert Umno-PAS pact”.

“This may convince Zahid that Pakatan Harapan may crack with more attacks … over religion and language. He may formalise the Umno-PAS pact by making Hadi Awang deputy prime minister in his shadow cabinet.”

Malaysia’s billion-dollar question: where did 1MDB money go?

A pact with PAS, however, would destroy Umno’s chances of forming a coalition government with the East Malaysian parties which control 57 seats, and harden non-Malays’ rejection of Umno in 113 peninsular constituencies with 20 per cent or more non-Malay votes, said Wong.

“Such a dim future may driv

e some Umno parliamentarians – Khairy Jamaluddin and Umno Sabah for example – to leave the party to stay in the middle ground,” he said.

However, many seem confident of a Pakatan Harapan victory as coda to their performance in the general elections, perhaps with just a lower margin of victory. With leader Anwar making appearances on the ground and lobbying for votes, coupled with the “local boy” factor, Sungai Kandis may well remain safely in the hands of the ruling coalition.

Whatever the outcome, the strategy from both sides of the political divide playing out in Sungai Kandis serves to underline that Malaysia still has far to go before breaking free from the race-based politics of the past.