Feuding dynasties, bloody massacres: Game of Thrones season 8 ... or Philippine politics?

In the ‘world capital’ of political dynasties, ruling families that have held power for decades trade positions like musical chairs. And when sibling or clan rivalries threaten this incestuous grip on power, things can turn deadly

Speaking in Filipino, the man, 48, revealed how all these years he had been bullied by his elder half-brother. “I always gave way. But there’s a limit. Now I have to stand for my principles.”

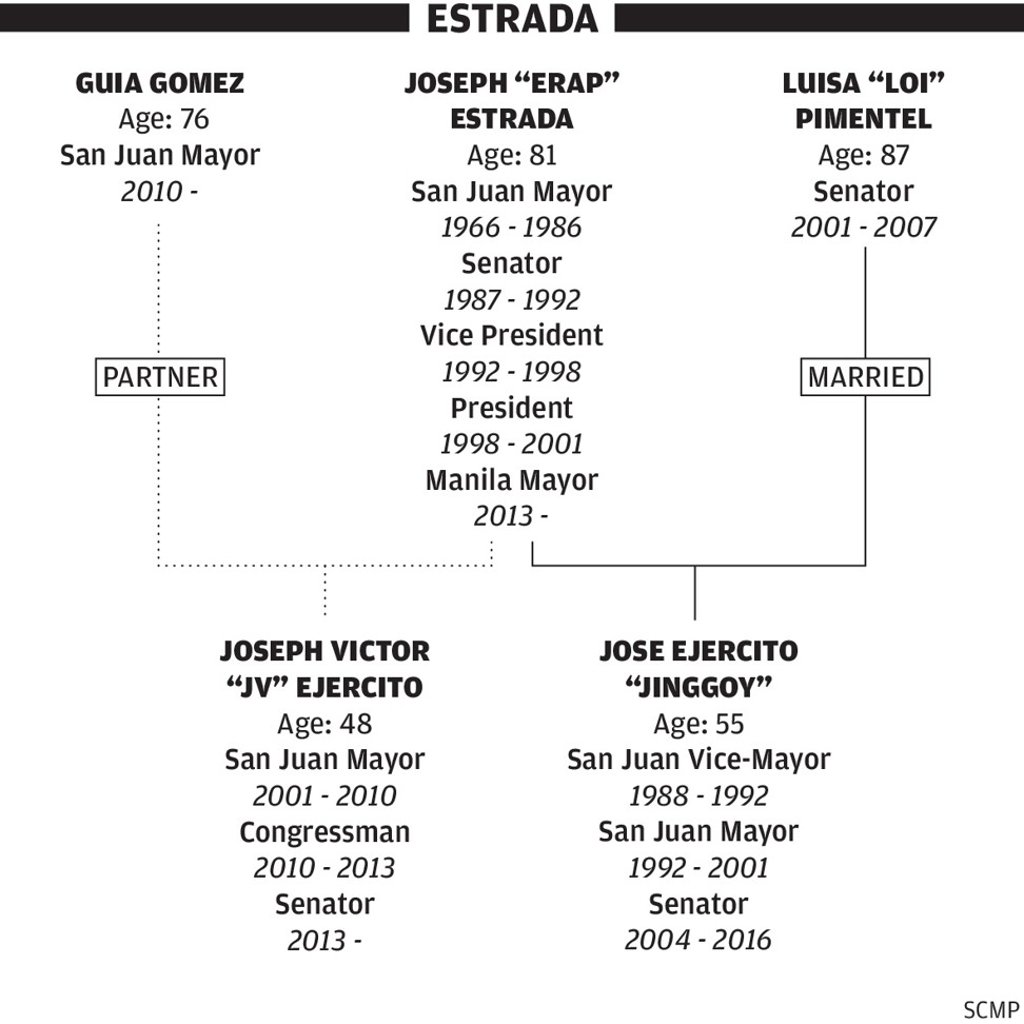

Aired on national radio last week, the line could have been lifted straight out of a daytime melodrama, a baring of what Filipinos call sama ng loob, hidden resentment. However, the character showing his anger was one of the country’s most powerful men: Senator JV Ejercito, son of disgraced ex-president Joseph “Erap” Estrada.

Ejercito was telling a news programme why he was running for re-election in May next year, pitting him against his half-brother, the former senator Jose “Jinggoy” Ejercito, 55. There is no love lost between the two. According to Jinggoy, “we’re not on speaking terms”. He has his own grounds for resentment: in 2014, when both were senators, Ejercito signed a Blue Ribbon Committee report that identified several colleagues implicated in the theft of billions of pesos in development (“pork barrel”) funds. Jinggoy Estrada was one of them. He was arrested and spent three years in detention before he was allowed to post bail last year. Ejercito himself was charged with corruption when he was mayor. He was acquitted last year.

The 81-year old Erap himself started as a mayor, then became senator, vice-president, president and is now back to being mayor of Manila, where he is running for re-election. His wife has been a senator, his common-law partner (Ejercito’s mother) is currently a mayor.