Can a ‘New Malaysia’ emerge while those in power play an old game?

- Public optimism rose to fever pitch following this year’s historic election that unseated a ruling coalition which had governed for nearly six decades

- But a new year brings with it fresh pessimism that the government of Mahathir Mohamad can deliver on its election promises

In the ensuing weeks and months, public confidence in the nation’s institutions rose to fever pitch and optimists began calling the country “Malaysia Baru” or “New Malaysia” after such a historic election.

But the new government also pedalled back on several election promises, much to the dismay of its most ardent supporters.

As the year comes to an end, the shine has come off and some of the old pallor of pessimism is back.

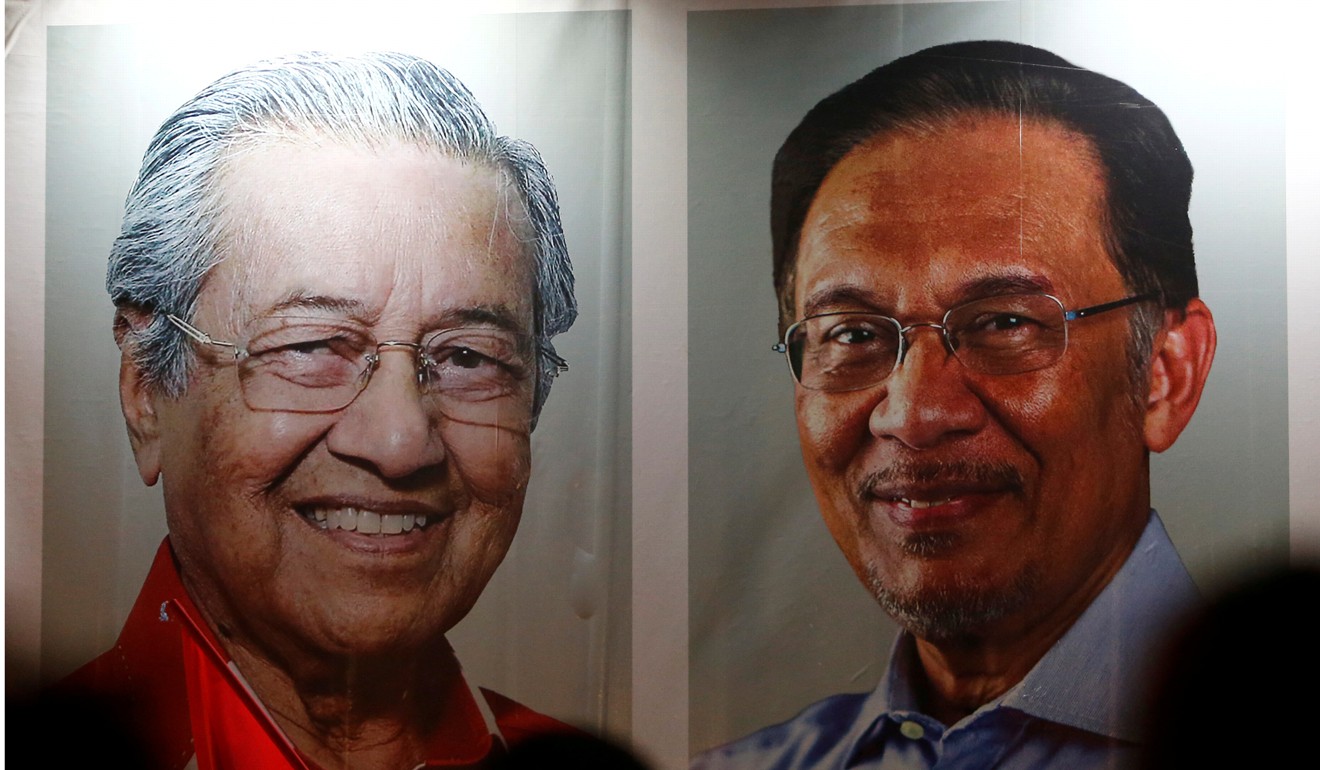

However, Mahathir, at the helm for a second time after ruling from 1981 to 2003, remains hugely popular. He has promised to step down to make way for Anwar Ibrahim – a former protégé who became an enemy but is now an ally once more – within two years, though no concrete succession plan or timeline has been confirmed.

It is unclear how long Mahathir will remain in charge but his second act has already redirected the political trajectories of his party, his coalition and his country.

And even as the new government puts up a brave show of unity, the structural problems that plagued “Old Malaysia” and issues of race and religion continue to determine and shape the nation’s politics, including within the coalition.

After the election, several senior figures within the deposed United Malays National Organisation (Umno), the leading party of the Barisan Nasional coalition, were arrested and charged with multiple counts of corruption and abuse of power. Umno responded with sabre-rattling, threatening riots and violence if the majority ethnic Malays were in any way crossed or short-changed.

Malaysia is a majority Muslim state, with ethnic Malays and indigenous groups – referred to as Bumiputra – accounting for 69.1 per cent of the population. Certain privileges, such as scholarships and housing discounts, are afforded the Bumiputra community. Ethnic Chinese and Indians have grudgingly accepted this perceived preferential treatment in the past and all too often, the rancour surfaces out in the open. Such racial sensitivities remain a core issue that Pakatan Harapan has tried to address – it promised but failed to ratify a United Nations treaty that would eliminate racial discrimination after opposition-linked groups claimed these special privileges would be lost.

Recent sectarian violence surrounding the move of a 167-year-old Hindu temple near Kuala Lumpur presented another test of Pakatan Harapan’s ability to govern this multiracial, multi-faith society.

Pakatan Harapan was able to form a government and won most of parliament’s 222 seats despite less than 30 per cent of Malays voting for the new coalition. The rest were divided between Umno and the nation’s Islamist party, PAS – a voting bloc that Pakatan Harapan cannot afford to ignore.

Even the post-election surge of goodwill did not counteract the top-down nature of Malaysian politics: jockeying for power within the parties that make up the coalition threatens to undermine the Pakatan Harapan government.

The temple violence resulted in the death of a firefighter, prompting cabinet minister Syed Saddiq – who belongs to Mahathir’s Malaysian United Indigenous Party (Bersatu) – to demand the resignation of fellow cabinet member and Unity Minister P. Waythamoorthy. Critics seized upon the lack of cohesion within cabinet, suggesting Pakatan Harapan was unequipped for the business of governing after decades as the opposition.

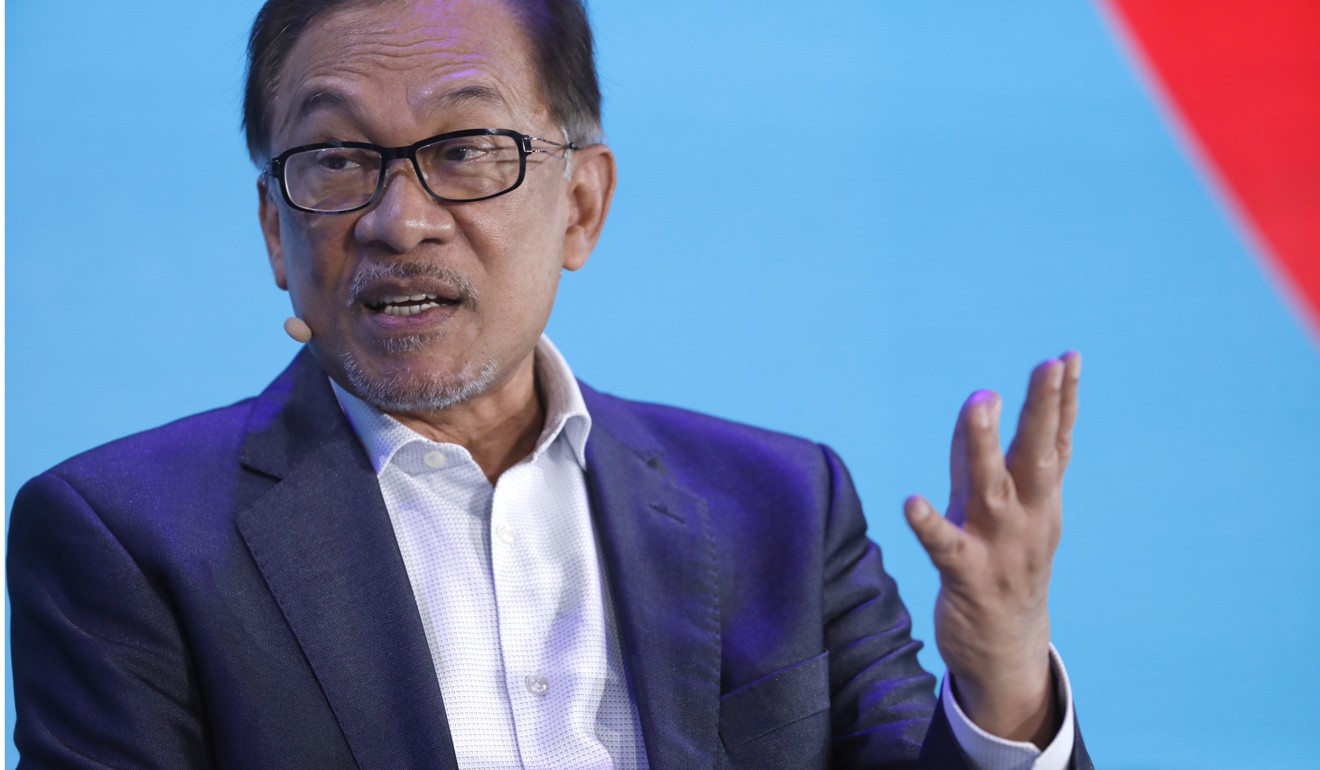

The internal polls in Anwar’s People’s Justice Party (PKR) were also plagued by violence, bribery and rumours of vote buying. PKR, which forms the largest parliamentary bloc, endured further turbulence when Anwar’s daughter, Nurul Izzah Anwar – whose mother is deputy prime minister Wan Azizah Wan Ismail – resigned from her party leadership roles. She was recently seen eating lunch with opposition stalwart Khairy Jamaluddin and PKR’s Rafizi Ramli, who squared off against Economic Affairs Minister Azmin Ali for the role of deputy president during the fraught PKR internal elections in November. Rafizi lost.

Wong Chin Huat, a political scientist at the Penang Institute think tank, suggested these twists and turns are hallmarks of Malaysian politics in transition.

“Communal politics will not go away with a centrist government in a democracy,” Wong said. “With multiparty competition, parties need to show voters they are different from each other, much like consumer products need product differentiation to build brand loyalty. In a plural society where different communities are constantly and jealously comparing what they have and what others have, religion and ethnicity are the natural basis of difference and differentiation.”

In new Malaysia, Anwar’s party faces an old problem

As a result, Wong said, Umno and PAS have embraced a more heavy-handed ethno-religious nationalism, in contrast with Pakatan Harapan’s centrist, multi-ethnic approach.

The flaw in Malaysian multiparty politics, according to Wong, is the winner-take-all model: power and resources for patronage are “highly concentrated in the hands of winners while losers can expect malnutrition if not starvation in resources”. In this environment, infighting is inevitable.

This jockeying for power was especially pronounced in the recent PKR polls but some observers cast the Azmin-Rafizi tussle as a proxy for a looming stand-off between Mahathir and Anwar, who was formerly Mahathir’s deputy. Anwar was imprisoned for sodomy in 1999 and again in 2014 – charges allegedly trumped up by Barisan Nasional to derail his bid for power – but was released and granted a royal pardon following the election victory.

Mahathir and Anwar were bitter enemies for the better part of nearly two decades after Mahathir sacked Anwar as deputy prime minister just days before his arrest for sodomy. This led to a “Reformasi” (reformation) movement – the street protests condemning Mahathir’s abuse of power cemented Anwar’s status as a democracy icon.

Najib says he’s ‘lucky’ to avoid sodomy rap over 1MDB probes

Mahathir eventually quit his former party Umno in protest over the 1Malaysia Development Berhad corruption scandal, in which former premier Najib Razak has been implicated. Mahathir and Anwar appeared to settle their differences in the lead-up to the election. However, insiders insist tensions and mistrust remain.

The struggle against old politics needs to be in the same vein as fighting corruption

Members of Umno have suggested neither Mahathir nor Anwar are satisfied with the deal. Both men are themselves former Umno leaders and many members have started declaring allegiance to one or the other in the hope of reclaiming a measure of federal power. Some have pinned their hopes on Anwar’s presumably inevitable ascendancy to the premiership, pledging parliamentary support despite Anwar refusing to let them join PKR. Others have thrown their lot in with Mahathir, leaving Umno to join Bersatu. More than 20 Umno members have quit since May, their reasons ranging from broken election promises to disillusionment with party leadership.

“The perception of the relationship between Mahathir and Anwar has worsened with this party hopping,” said Awang Azman Awang Pawi, a political scientist at the University of Malaya. “There are concerns of personal political positions being lost or adapted when Anwar is appointed as premier.

“However, the era of new feudal politics and warlords that were essential to strengthening parties and positions alone should be rejected. The struggle against old politics needs to be in the same vein as fighting corruption.”

In short, Malaysia may struggle to implement “Malaysia Baru” (a New Malaysia) while the old dynamics remain in place. Indeed, these dynamics could prove more enduring than any of the individuals involved.

We need real visionary leaders – who can be 93 or 39 or any age – to reconfigure politics and not just strive to win in the old game

The New Malaysia promised by Pakatan Harapan before it formed a government is, according to Wong, “not yet born and will not be born until we change the inner logic of political competition and transform politics”.

“Most voters won’t care about [the] political system, dynamics and incentives politicians and parties face,” Wong said. “They just want the ideal outcome – stability, moderation, accountability, competence. For that to happen, we need real visionary leaders – who can be 93 or 39 or any age – to reconfigure politics and not just strive to win in the old game.”

Unless Pakatan Harapan takes real steps in this direction, further party-based realignments and turbulence will be inevitable in 2019. This is likely to include tensions within PKR and between PKR and Bersatu, which will in turn engender political fatigue and disillusionment among the public. Wong echoes the sentiments of many watching on the sidelines: “This is dangerous for Malaysia’s fragile reborn democracy.”