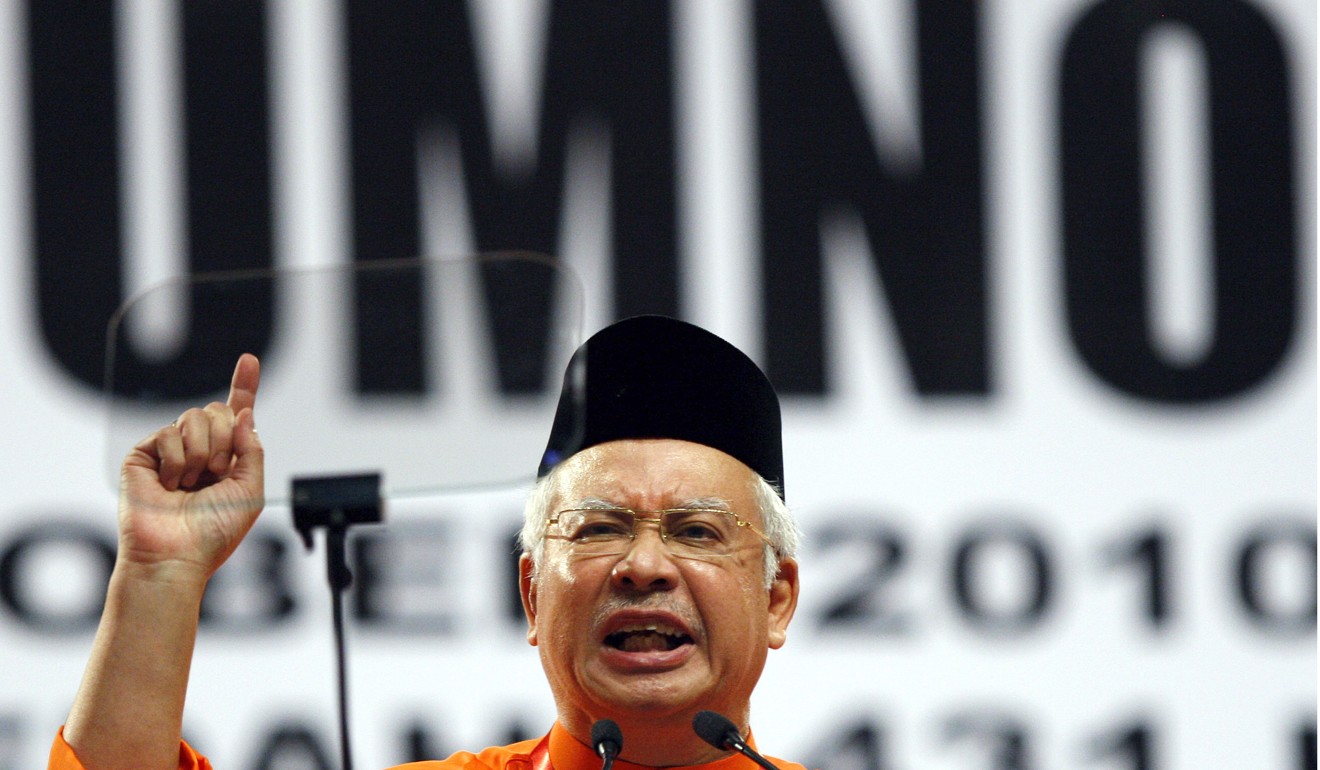

Fight club: Najib Razak’s Umno recruiting ‘bruisers’ in battle to regain control of Malaysia

- Party of disgraced former premier is undergoing transformation as it targets rural support base, but stacking leadership with ‘fighters’ comes with risks

- This is the fourth of a four-part series on Malaysian politics a year on from the Pakatan Harapan coalition’s historic election victory on May 9, 2018

A year on from Malaysia’s watershed general election, its new opposition forces are scattered and weak, a far cry from their previous power. But this may soon change if the United Malays National Organisation (Umno) succeeds in its unofficial rebranding, turning itself from a party led by blue-blooded elites into one helmed by rough and tumble grass-roots leaders.

Scooping only 54 of 222 parliamentary seats, the Malay party soon faced a series of hurdles including defections, leadership issues, and charges against several members over corruption – the most prominent of which was former premier Najib Razak, who is facing more than 40 charges related to the 1Malaysia Development Berhad global financial scandal.

But a year on, the opposition is making steps towards recovery.

Among those leading the charge is Supreme Council member Lokman Noor Adam, a self-styled “fighter” who warns that Pakatan Harapan policies threaten to leave the Malays behind.

The party now, he says, needs bruisers ready to push the agenda and call out the government.

“My popularity after the elections was high because I was the only one fighting against the government. The others were quiet. I knew they wouldn’t fight so I had to be the role model to start it first.”

A year since victory, can Mahathir run Malaysia’s economy without blaming Najib or ‘1MDB mess’?

Lokman maintains that the opposition is not promoting hatred, but merely responding to “provocations” from other groups.

“We can only pressure them, incite back. At this moment ... nothing much we can do. We are weak. Umno and PAS are very weak. We won [previous by-elections] not because we are strong. We won because we are united,” says Lokman, who was previously aligned with Parti Keadilan Rakyat, the party of democracy icon and prime minister-in-waiting Anwar Ibrahim. Like his former leader, Lokman has spent some time behind bars: he was detained twice under the now-repealed Internal Security Act.

Lokman insists that the positive discrimination in favour of the bumiputras – a term used to refer to majority Malays and indigenous people who make up 70 per cent of the population – was agreed upon before independence in the 1950s as part of the “social contract”, and so cannot be questioned.

“Of course you can say that it is not fair for the Malays to have certain quotas. But ... we already agreed. The British asked the Malays to give Indians and Chinese citizenship, those who they brought in without our permission after we were colonised,” says Lokman.

Former Malaysian PM Najib Razak fails to have corruption charges overturned

One of the party’s most recognisable figures post-election, the portly, fiery Lokman represents a new Umno man: one who is a far cry from the patricianly blue-bloods that previously symbolised the party like Najib, who is the son of Malaysia’s second premier, and Hishammuddin Hussein, son of the third.

This Malay nationalist Umno and its partner PAS, says political scientist Wong Chin Huat, enjoy majority support from Malay-Muslims and may indeed grab further ground.

“Such a monoethnic opposition bloc has no incentives to be moderate, but would instead do everything to attack the government for selling out Malay-Muslims.”

This, says Wong, limits Pakatan Harapan’s ability to undertake reforms or correct any marginalisation of minorities, frustrating its minority base “even though they don’t have better alternatives”.

Without mainstream Malay support, Pakatan Harapan faces certain defeat in the next election – a fact that Umno is well aware of.

“Pakatan Haparan voters are mostly Barisan Nasional voters,” asserts Umno stalwart Razlan Rafii.

“Then they realised the promises are not being kept, so they returned to us.”

Malaysia won’t back down on sensitive issues even as it bolsters economic ties with China, Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah says

At odds with Lokman and his camp, some members of Umno maintain that the non-Malay voters should remain an important factor in the party’s strategies. Politicians such as Oxford-educated Khairy Jamaluddin, formerly the youth and sports minister, have pushed for an inclusive, multiracial approach, warning that deciding to “play race and religion” with PAS will not be enough. In a widely shared tweet last year, he dismissed Lokman as “having the IQ of a carrot”.

Supreme Council member Shahril Hamdan believes that recent by-election results have shown Umno enjoying a swing back from “disgruntled multiracial votes who are not happy with Pakatan Harapan”, along with core Malay support. If this continues, he says, Pakatan Harapan will be a one-term government. But in the meantime, Umno must work to connect with Indian and Chinese voters.

“Winning the majority of Malay votes alone is not enough. We also need a sizeable number of the non-Malay vote,” says Shahril, who insists that the opposition needs a substantive policy framework to appeal to both Malay and non-Malay voters, rather than being seen as just “capitalising on short-term Malay sentiment”.

Khairy and Shahril, who holds a master’s degree from the London School of Economics, are currently setting up a research outfit founded on centrism, named The Centre.

I’d side with rich China over fickle US: Malaysia’s Mahathir Mohamad

These more measured approaches, however, will not bear immediate political benefit, says Wong.

“Under the current system, where Umno’s remaining strongholds are Malay majority, and the prospect of forming an Umno-led multiethnic government is almost zero, moderation is not electorally rewarding.”

Only if circumstances turn so that Umno can no longer depend on “PAS’ heavy dose of ultra nationalism” will moderates like Khairy be “treasured as assets”.

But Umno members like Khairy and Shahril appear to be in the minority. Even disgraced former premier Najib appears to have embraced a more informal approach, working on becoming relatable to the man on the street.

Once mocked for admitting he ate quinoa instead of rice, Malaysia’s staple food, Najib now is spotted in hoodies and astride low-end motorcycles, painting himself as an everyman Malaysian. On Instagram, Najib has posted photos of himself on motorbikes, barefoot in lakes, working out at the gym, playing with his cat Kiki, and visiting local markets. On Facebook, he launches regular salvoes at the government, questioning their economic moves and failure to uphold various election pledges.

Armed with the tagline Malu apa bossku? (what is there to be ashamed of, boss?), Najib is enjoying renewed support from the electorally influential rural Malays even as he is on trial for 1MDB-linked charges of money laundering and abuse of power.

1MDB corruption trial: Malaysia’s ex-prime minister Najib Razak’s returns to court on US$10.3 million theft charges

The charges, supporters say, are trumped up by the government to put its biggest critic behind bars. Others believe he was “tricked” by financier Low Taek Jho into making dodgy agreements. Najib and his wife Rosmah Mansor, who some critics say was the key to his undoing due to her fondness for expensive jewellery and Birkin handbags, have not been seen together in public in recent weeks.

But rebranding efforts need to appear sincere, warns analyst Awang Azman Awang Pawi of University Malaya’s Institute of Malay Studies.

“Umno needs politicians who are sincere in championing the issue of the people consistently, not only when they lose or become mere opposition. Prior to this, Umno’s leadership was upper-middle class. Now when the voice of this elite political nobility tries to turn into a working class voice, it comes off odd and paradoxical.”

Lokman, however, insists that the voters are buying what Umno has put down – and Najib can still serve as a rallying force.

“The people will want him [back]. That’s why I have been supporting all this time,” insists Lokman, who named his son after the embattled leader. “His support is much better than before his premiership. Before this I never saw people crying, waiting for the chance to hug him. His career is not over.”

This is the fourth of a four-part series on Malaysian politics a year on from the Pakatan Harapan coalition’s historic election victory on May 9, 2018

Continued from p.13

Continued on p.14