Japan: now open to foreign workers, but still just as racist?

- Japan is opening its doors to blue-collar workers from overseas to fill the gaps left by an ageing population

- Resident ‘gaijin’ warn that the new recruits – whom the government refuses to call ‘immigrants’ – might not feel so welcome in Japan

Japan’s reluctance to allow foreigners to fill the gaps in its labour market has finally crumbled, as the country begins issuing the first of its new visas for blue-collar workers from overseas.

Teething problems appear all but inevitable given the nation is famously insular, is not experienced with large-scale immigration and has a deep distrust of change.

Companies struggling to find enough employees as the population ages and fewer young people enter the workforce have broadly welcomed the new immigration rules – though there are still many who insist that the government has made a mistake and that local people’s jobs and social harmony are at risk. Ultra-conservatives, meanwhile, are railing at the potential impact on the racial purity of their island nation.

And there are foreign residents of Japan who fear the new rules may encourage even more overt discrimination against “gaijin”, or foreigners, than already exists. According to government statistics, there are 2.217 million foreign residents of Japan, with Koreans, Chinese and Brazilians making up the largest national contingents.

The new visa has two versions, both requiring a company to sponsor the foreign worker and provide evidence that he or she has passed various tests, including on Japanese language ability.

Fourteen industries – including food services, cleaning, construction, agriculture, fishing, vehicle repair and machine operations – are covered by the first visa, aimed at those with limited work skills. The worker’s stay is limited to five years, with the option of visa renewals, but they are not permitted to bring their family members to Japan.

Industry analysts say the issue needs to be addressed urgently, although they also warn that the 47,550 visas that are expected to be issued in the first year of the new scheme, and the total of 345,000 over the initial five years, will still fall well short of what domestic industries require.

Japan’s open to foreign workers. Just don’t call them immigrants

“Government statistics and industry are both telling us that the labour market is completely empty,” said Martin Schulz, senior economist for the Fujitsu Research Institute in Tokyo.

“But in truth, Japan has no choice but to open up to foreign workers,” Schulz said. “Even with more automation and robots, there are simply not enough people.”

Yet there has been significant resistance among those who fear their jobs will be taken by foreigners who will work longer hours for lower wages, those who say outsiders will cause problems because they will be unable to assimilate into Japanese society or struggle with the language barrier.

The concerns about foreigners settling in Japan cut both ways, however. Very often, according to French expat Eric Fior, it’s the relatively minor but persistent incidents of discrimination in Japan that get under his skin. Such as the time it snowed heavily one winter and the janitor of the building in Yokohama where he had his office shovelled the snow away from every door in the building. Except his.

Japan is such a polite country ... but there are times you get the sense that not far below the surface is the wish that us foreigners were just not here.

Or the time he confirmed with the management of the property that he could have some flower boxes outside his office door, just like the other tenants, and he was given permission to do so. Three days after he positioned the flower boxes, the nearby tap he used to water them was disconnected.

He asked the janitor where it had gone and got a shrug in reply. As the man turned away, Fior could see the tap in his pocket.

“What can you do?” said Fior, 47. “Japan is such a polite country on the surface and everyone smiles and bows, but there are a lot of times when you get the sense that not far below the surface is the wish that us foreigners were just not here.

“But there really is little point in confronting them as nothing will get done and we just end up with the reputation of ‘foreigners who cause problems’,” he shrugged.

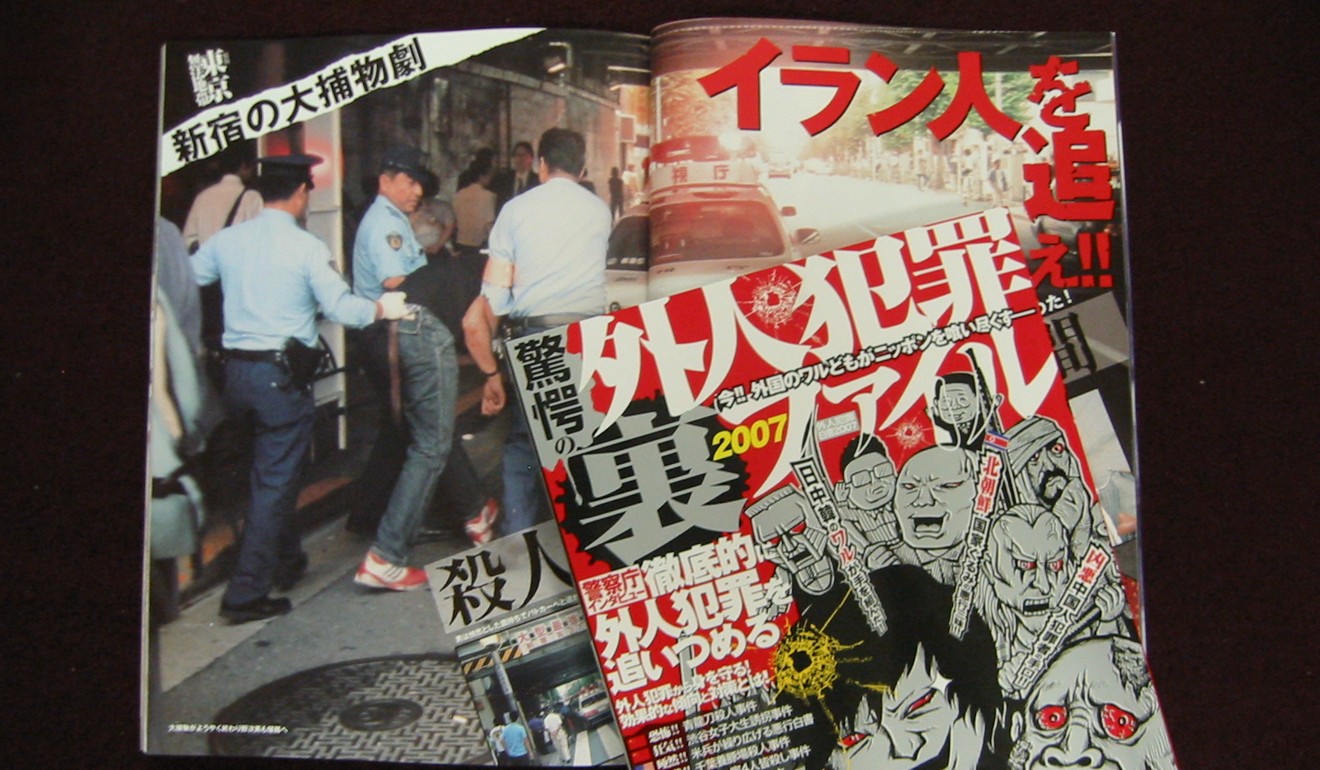

Reports of discrimination against the foreign community in Japan are countless and varied – from landlords who refuse to rent to non-Japanese for no apparent reason other than their nationality, commuters who refuse to sit next to a foreigner on a packed train or signs at the entrances to bars or restaurants baldly stating “No foreigners” – but a new study indicates the scale of the problem.

Why is racism so big in Japan?

Conducted by the Anti-Racism Information Centre, a group set up by activists and scholars, 167 of the 340 foreign nationals who took part in the study said they had experienced discriminatory treatment at the hands of Japanese.

Replying to the study, a foreign part-time shop employee recalled a Japanese customer who did not like seeing foreigners working as cashiers, refused to be served by them and demanded Japanese staff. Another response to the study noted the case of a Chinese employee of a 24-hour store who was reprimanded after speaking with a Chinese customer in Chinese and ordered to only speak in Japanese.

Others reported being refused rental accommodation or denied access to shops.

Activists point out, however, that the Japanese government’s new regulations that relax visa requirements for workers from abroad mean that there will soon be tens of thousands of additional foreigners living in Japanese communities.

“It’s a net positive that Japan is bringing over more people, since that may help normalise the fact that non-Japanese are contributing to Japanese society,” said Debito Arudou, author of Embedded Racism: Japan’s Visible Minorities and Racial Discrimination.

“But it is disappointing that Japan still is not doing the groundwork necessary to make these newcomers want to stay and contribute permanently,” he said. “The new visa regime still treats these non-Japanese entrants as ‘revolving-door’ workers, with no clear path to permanent residency or citizenship.

“And – as the surveys seem to indicate – one fundamental flaw in these plans is that non-Japanese are insufficiently protected from the bigotry found in all societies,” Arudou said.

“Japan still has no national law against racial discrimination, remaining the only major industrialised society without one. Even government mechanisms ostensibly charged with redressing discrimination have no enforcement power.”

Dumplings, tai chi and a hint of racism: a Chinatown takes root in suburban Tokyo

Tokyo needs to pass the laws that make racial discrimination illegal, empower oversight organisations and create an actual immigration policy instead of a “stop-gap labour shortage visa regime”, he said.

“At the very least, tell the public that non-Japanese workers are workers like everyone else, filling a valuable role, contributing to Japanese society and are residents, taxpayers, neighbours and potential future Japanese citizens,” he added.

Discrimination is arguably felt more by people from other Asian nations than Westerners, while even Japanese women are often described as second-class citizens purely as a result of their gender.

“Despite fulfilling the requirements for a Japanese guarantor and having bank statements, there were many occasions when I was refused,” she said. “Back then, going to an ‘onsen’ or restaurant with ‘gaijin’ friends was a pain, too. If none of us looked Japanese enough, we were refused entry right at the door.”

“Japan has always been a homogenous society and so the default mindset here is that anything alien to them gets scrutinised and is not trusted,” she said. “But having a win-win attitude will get you on their good side.” ■