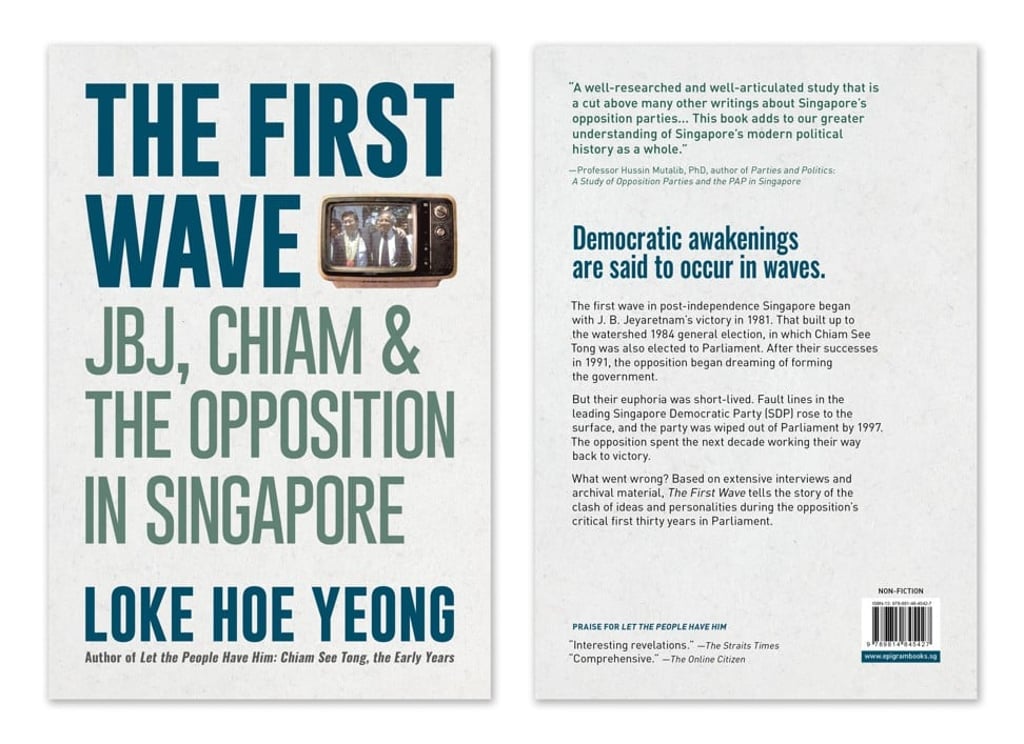

From JB Jeyaretnam’s 1981 election win to Chiam See Tong’s collapsed political alliance: new book details rise and fall of Singapore opposition

- ‘The First Wave’ is a new book on Singapore’s opposition parties and the role they played in the country’s political development between 1981 and 2011

In 1981, the late opposition politician J.B. Jeyaretnam won a by-election and disrupted the dominance of the ruling People’s Action Party in Parliament. While seats were won by opposition politicians such as Chiam See Tong in subsequent elections, these were in single-member constituencies. The opposition parties also struggled with internal strife and were not able to make significant gains until 2011, when the Workers’ Party won a clutch of seats at one go in a group representation constituency.

The book, published by Epigram Books, is available for S$34.90 online and at major bookstores. Here are excerpts of the book:

Chapter 4: Chiam Alone

Jeyaretnam disqualified from Parliament

In 1982, Jeyaretnam and Wong Hong Toy, the chairman of the Workers’ Party and a long-time opposition activist who resuscitated the party together with Jeyaretnam around 1972, had each faced a charge of making a false declaration about the Workers’ Party’s accounts to a commissioner of oaths. They had stated that the accounts, as prepared by the Workers’ Party treasurer, reflected a true and fair view of the party’s financial position in the first half of 1982, whereas the prosecution alleged that they omitted three donations in the form of cheques totalling S$2,600 during that period. The amount of those three donations was paid to the law firm of R. Murugason and Company, the personal account of Wong, and “an unknown person”. The charge from the prosecution was that they did so to prevent the distribution of party funds to the creditors of the Workers’ Party, which included former PAP MP Tay Boon Too, who had successfully sued Jeyaretnam for defamation in a case dating back to the early 1970s and was pressing the Workers’ Party to settle a long-standing debt.