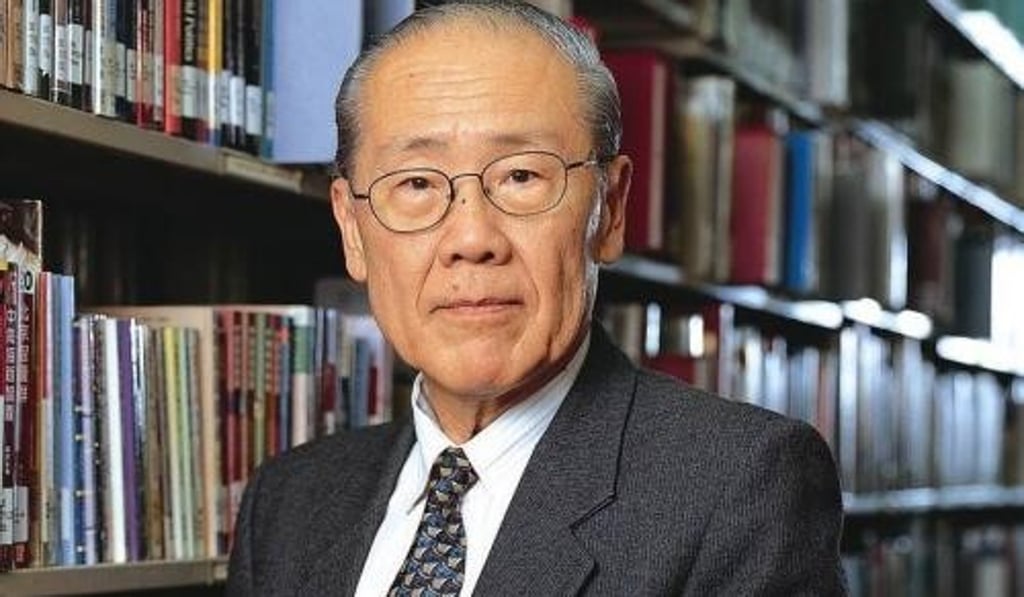

Ancient past, modern ambitions: historian Wang Gungwu’s new book on China’s delicate balance

- China Reconnects: Joining a Deep-rooted Past to a New World Order looks at how the Middle Kingdom is trying to build a modern civilisation without forgetting its heritage

China Reconnects: Joining a Deep-rooted Past to a New World Order is a new book by Australian historian Wang Gungwu. The book seeks to explain the new-found confidence among the Chinese in their capacity to learn all they need from the developed world while retaining enough from their past to build a modern civilisation. It does not employ theoretical frameworks to explain China’s rise, as Wang believes they are not appropriate to describe the changes sweeping the country. He calls for greater understanding of why history is particularly important to the Chinese state and its people, as the nation seeks the means to respond to a United States trying to preserve its dominant position in the international status quo.

Wang is university professor at the National University of Singapore and professor emeritus of the Australian National University. The book is published by World Scientific Publishing. Here are some excerpts.

CHINESE CHARACTERISTICS

Xi Jinping’s China inherited the policies that opened the country to the global economy. The policies created the conditions that made China prosperous and, to many, they put China on the world map again. At the same time, what Xi Jinping inherited also includes practices and lapses of discipline that led to corruption on an unprecedented scale. Deng Xiaoping might have expected some leakages in a more open system, but would not have thought that his party cadres could succumb to that extent.

Xi Jinping also inherited programmes from his predecessors “theories” like sange daibiao (Three Represents) and hexie shehuizhuyi shehui (Harmonious socialist society). Given the pervasive corruption that he found in high places, he must have wondered how useful these theories were. The former was implicitly socialist, stressing productive forces, advanced culture and concern for the interests of the majority. The latter, however, was redolent of Confucian values, made even more explicit when Hu Jintao spoke of barong bachi, or “eight honours and eight disgraces”. Despite these exhortations, the corruption that accompanied them reminds us of conditions familiar to Chinese dynasties in decline.