Gay sex: is time finally up for Singapore’s Section 377A?

- The Lion City still clings to a colonial-era rule that outlaws sex between men

- Campaigners hope legal cases starting this week will herald an end to Section 377A but analysts say it is unclear if this is what the majority of people want

It is a law famously and stubbornly resistant to change. One that has outlived not only the British colonialists who drafted it, but the British empire itself. A law that survived the birth of an independent nation and a new millennium; a law rooted in the 19th century that still causes arguments well into the 21st.

Yet after 80-plus years on the statute books, gay rights campaigners hope time could finally be up for Section 377A of Singapore’s Penal Code.

The law, which criminalises sexual acts between men, is to face three legal challenges starting from this week, in cases likely to polarise opinion in the city state.

Singapore is one of the few remaining former British colonies still clinging to the archaic rule, which came into force in 1938 after being adapted from a 19th-century Indian penal code (abandoned by India last year). And while the city state no longer enforces the law, gay rights campaigners argue that its symbolism is socially corrosive, that it encourages discrimination and undermines the principle of equality.

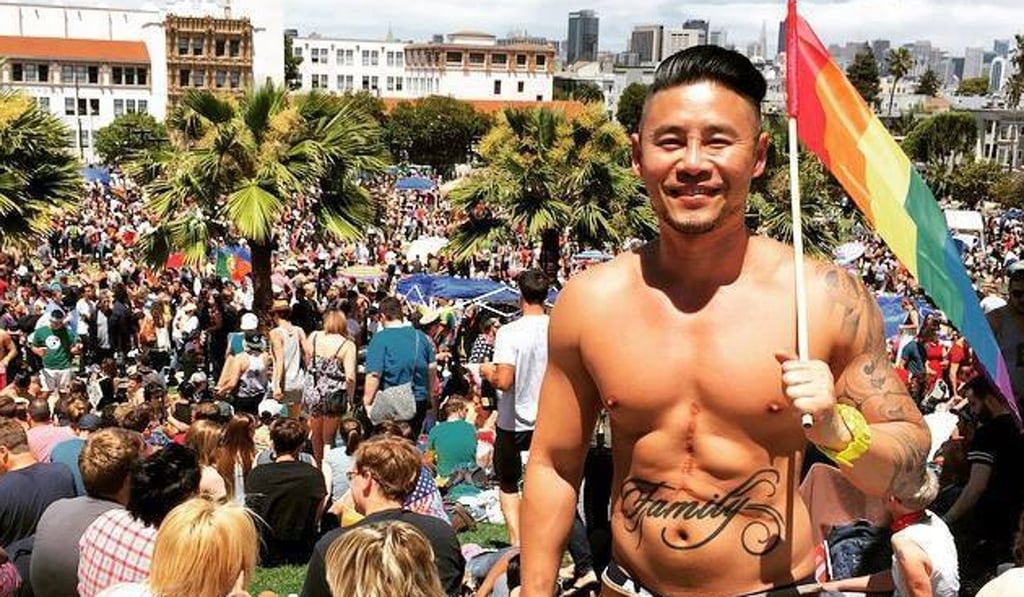

Amid new research suggesting younger Singaporeans’ attitudes to gay rights are liberalising, the cases filed by Roy Tan, a former organiser of the Pink Dot gay rally, disc jockey Johnson Ong Ming, and Bryan Choong, a former leader of the non-profit organisation Oogachaga, will be seen by many as a litmus test for the government.