Advertisement

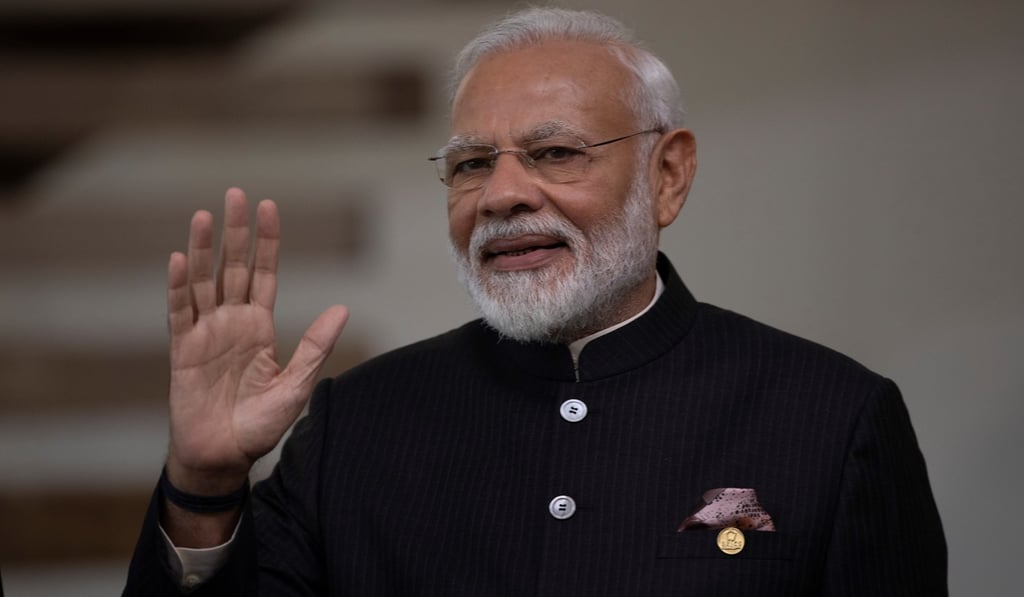

Ceritalah | All talk aside, does Narendra Modi have a real solution to India’s economic woes?

- India faces rising poverty and an unprecedented drop in consumer spending. Manufacturing is haemorrhaging and the financial sector is in free-fall

- The slogan ‘Make in India’ has been forgotten despite the vast opportunities presented by the US-China trade war

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

Back in 2014 when Narendra Modi was first elected, he set out to transform the underperforming Indian economy. He promised to replicate the success of his home state, Gujarat, across the republic, creating a surge of jobs and opportunities for all.

Instead, five years on, following a deeply divisive election, a National Statistical Office survey shows India faces rising poverty, especially in rural areas, as well as an unprecedented drop in consumer spending.

The 2017-18 survey reflects how acutely two poorly conceived policy initiatives – a bungled goods and service tax and demonetisation – affected small-town India.

In light of the weak economy, Modi and his BJP cohorts switched strategies for this year’s election. The 2019 campaign was fought on an aggressively Hindutva and anti-minority platform. They also ramped up the perceived threat of Pakistan and terrorism, launching a cross-border air strike on Balakot in February. In August, shortly after the election, New Delhi ordered a brutal lockdown of the majority Muslim state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Advertisement

Meanwhile the economy remains deeply troubled.

Manufacturing is haemorrhaging. The slogan “Make in India” has been forgotten despite the vast opportunities presented by the US-China trade war, many of which have instead been scooped up by Vietnam and other Asean nations. Indeed, the decision to pull out of the RCEP trade deal underlines India’s inability to compete globally, reinforcing the nation’s inward-looking stance.

Advertisement

The once booming auto sector – estimated to constitute some 40 per cent of manufacturing output and 7 per cent of overall GDP – is in reverse with a staggering 23 per cent year-on-year decline. Motorbike sales also plummeted 16 per cent between April and September this year.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x