Are Indonesia, Vietnam and Malaysia about to get tough on Beijing’s South China Sea claims?

- When Indonesia sent warships to the Natunas this week, it became the latest Southeast Asian nation to stand up to China’s maritime assertiveness

- Vietnam and Malaysia are likely allies in the cause, but Chinese patronage means other countries will be less inclined to make waves

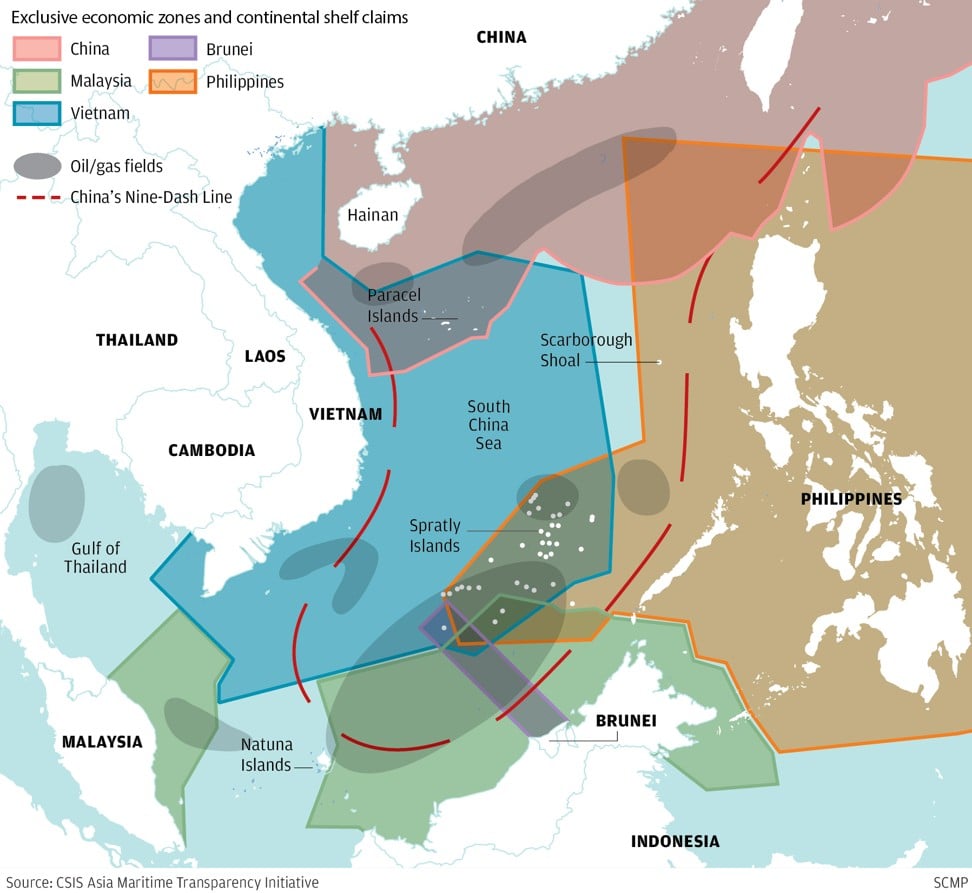

The Natunas, which lie roughly 1,100km south of the Spratly Islands, are at the centre of a spat between Indonesia and China that this week forced its way into headlines across the world.

They are surrounded by resource-rich waters that China claims as part of its traditional fishing grounds and to reinforce these claims Beijing has in recent weeks sent coastguard ships to escort its fishing vessels into the surrounding area.

Can Vietnam unite Asean against Beijing’s South China Sea claims?

On Wednesday, that prompted a forceful response from Jakarta, which deployed fighter jets and warships to the islands ahead of Widodo’s visit and said it would send hundreds of fishermen to the Natunas to keep an eye out for foreign vessels.

Yan Yan, director of the Research Centre for Oceans Law and Policy at the Chinese government-backed National Institute for South China Sea Studies, said Indonesia had been taking increasingly tough measures to defend the waters off the Natuna Islands from other countries.

“China recognises Indonesia’s sovereignty in the Natuna Islands,” said Yan in an article for the institute. “The dispute is mainly about fishing rights, it should not be escalated to a political and territorial one.”

But since the spat this week, its officials have invoked the 2016 ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, which ruled that the nine-dash line marking Beijing’s territorial claims in the South China Sea had no basis in international law, as evidence of China’s overreaching maritime claims.

Explained: Asean

Malaysia, too, has shown signs of defiance, last month submitting to the United Nations its claims for an extended continental shelf that directly overlapped China’s territorial claims.

“These recent incidents could catalyse Indonesia to put more effort into pushing for an Asean consensus towards China [and] the Code of Conduct,” said Collin Koh, research fellow at Singapore’s S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS).

Le Hong Hiep, a research fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, said Beijing’s rejection of the 2016 ruling risked alienating its friends in the region and had provoked claimant states to challenge it.

“Beijing is facing a dilemma,” said Hiep. “If [the Chinese] want to assert their claims, they have to pretend the ruling had no effect on their status. But by doing so, they will anger other claimant states, which could tempt them to take stronger actions, including challenging their presence.”

PUSHING BACK

Vietnam’s deputy foreign minister Nguyen Quoc Dung last month called on Beijing to show restraint and described China’s behaviour in the South China Sea – through which more than US$3 trillion in trade passes every year – as alarming and threatening to both Vietnam and other countries.

Chinese oil survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8 spent more than three months in Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone last year, in what Hanoi said was a violation of its sovereignty.

Malaysia released its first defence white paper late last year, naming both the US and China as sources of tension in the sea. Experts say that the submission of the extended continental shelf claims, which significantly conflict with China’s, shows Malaysia’s support for the 2016 Hague ruling.

But observers say Indonesia will not be as accommodating.

Has the US already lost the battle for the South China Sea?

“Sure, we have good economic and financial ties with China, but the issue is perceived differently domestically in Indonesia,” said Evan Laksmana, a researcher at Jakarta’s Centre for Strategic and International Studies. “The government, political elites and society are all rallying behind taking a stronger stance. No one wants to be seen as trading economic goods for sovereign rights in the water.”

Beijing should be concerned about losing friends among Asean nations over its disregard for the tribunal ruling, said Hiep at ISEAS.

China’s assertive behaviour in the sea could mean Southeast Asian nations would be unwilling to come to its aid in the event of a confrontation with the US, said Hiep. “China has focused on flexing its muscles and forced other Asean claimant states to react strongly,” said Hiep.

“Beijing should refine its approach to advance its national interests while not losing the good friends and partners it has in the South China Sea region.”

KEEP TO THE CODE

The Code of Conduct for the South China Sea could be the best chance for Asean nations to short-circuit the spiral of escalatory behaviour and mistrust over the maritime disputes which had led to increased arms sales and fears of confrontation in the region, said Zhang Baohui, professor of political science at Lingnan University in Hong Kong. “If they can achieve a robust Code of Conduct, Asean nations can afford to trust other countries more,” said Zhang.

A draft negotiating text of the code was put forth in 2018, with the aim of agreement by 2022. Moving negotiations forward is widely expected to be a central focus of Vietnam’s Asean chairmanship this year.

Former Singapore foreign minister George Yeo said in a speech in Hanoi this month that “whether the code between Asean and China can be signed in Brunei [in 2021] depends a great deal on the progress made this year under Vietnam’s chairmanship”.

“Historically, the South China Sea has been the link between Southeast Asia and China,” said Yeo. “The sea connected us, it never divided us.”

‘The South China Sea connected us, it never divided us’: how Asean can build bridges

But while they hoped for a multilateral solution, nations in Southeast Asia, especially those with claims in the South China Sea, were still hedging by building up their militaries, said Zhang.

One aspect under consideration in the code could forbid military operations as well as oil exploration in the area by outsiders without the unanimous consent of all Asean states plus China, which some observers say would effectively give China veto power over military activities and resource exploration in the waters.

This would mean other powers looking to establish an economic or military presence in the area – including the US, Japan and Australia – would need Beijing’s approval, hampering Washington’s efforts to counter China’s growing influence in the region.

Beijing has preferred a bilateral approach to resolving disagreements.

Since the 2016 ruling, China and the Philippines under Duterte have engaged in a bilateral consultation mechanism on the South China Sea. China also set up bilateral talks with Malaysia in September last year following tensions over their overlapping claims.

“China has shown it has a more tailored approach to individual Southeast Asian states, no single playbook or one-size-fits-all approach,” said Laksmana.

Ding Duo, assistant research fellow at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, said the code could also keep disputes between Asean nations and China between the parties involved, rather than have them come under the purview of international institutions.

“One of China’s main goals in the region is to resolve the territorial and maritime disputes peacefully and properly through direct negotiation between parties,” said Ding.

The code could formalise this arrangement and keep disputes at the bilateral level.

“The whole idea of the code is meant to show that South China Sea disputes should be resolved and managed by Asia only, and outsiders are not welcome,” said Koh at RSIS. “The code is meant to showcase and propagate this narrative.”

ASEAN, DIVIDED

Complicating matters is a maritime dispute between Indonesia and Vietnam, which flared up early last year when a Vietnamese fishing surveillance vessel rammed an Indonesian navy ship.

Indonesia’s former fisheries minister Susi Pudjiastuti had a policy of sinking boats found illegally within Indonesian waters, and more than half of the vessels destroyed under this policy belonged to the Vietnamese. Observers say the two are not likely to patch up the relationship any time soon.

Other neighbours may be ambivalent on the issue. Because Cambodia and Laos do not have claims in the South China Sea, they are seen as being unlikely to side against Beijing, especially because both receive substantial Chinese aid.

Analysts are hoping a repeat of the 2012 summit, the first time it failed to produce a communique, can be avoided. In a low point for Asean unity, Cambodia during its chairmanship that year sided with China to block a joint communique that would have addressed the bloc’s differing viewpoints on the South China Sea.

Each Asean nation has its own relationship with China, and even the situations of claimant states in the South China Sea vary widely.

Experts say Asean’s disunity will keep individual nations dealing with China on a bilateral basis – which could prevent the bloc from adopting a unified voice against China’s behaviour in the South China Sea, and make it difficult to get consensus on the Code of Conduct.

“Myanmar is far from the South China Sea, Laos is landlocked, and Cambodia doesn’t see the South China Sea as important as Chinese economic aid and investments,” said Koh.

“These diverse interests and approaches make it hard to take a united stance – the idea of a unified Asean stance on South China Sea issues is more aspirational. That won’t stop other countries from pushing for consensus on some issues, but it’s a tall order.”

China has deepened its economic engagement with the region, becoming the third-largest source of foreign direct investment last year. Experts also say Southeast Asian nations will not want to jeopardise the vital economic ties.

Zhang Baohui said: “Obviously Vietnam has a lot at stake, but that doesn’t apply to all the other Asean countries. If they join Vietnam on this issue, that would effectively mean changing their China policy, and, from their perspective, why should they? They value their good relations with China.” ■