Coronavirus models made governments take action, but how useful are they really?

- Infectious disease modelling helped convince countries to make extraordinary moves in a bid to curb the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic

- But how these models work is little understood by either policymakers or the public, and there is growing scepticism about some of their predictions

Why UK’s coronavirus death toll is likely much higher than official tally

The dramatic policy U-turn was a striking, but far from isolated, example of the extraordinary influence that computer models have had on how governments around the world are responding to the pandemic, which has resulted in more than 2.6 million confirmed infections and about 190,000 deaths so far.

Although models have been part of the toolkit for fighting infectious disease since the 1800s, their enormous impact on policymaking during the pandemic has raised questions about their accuracy, limitations and risks – including whether authoritative-sounding calculations may ironically blind governments to their full range of options when tackling a crisis with ramifications for every aspect of society.

When modellers made the decision to look at certain public health interventions over others, for example, it could lead governments to formulate responses that might be less effective, said Yaneer Bar-Yam, president of the New England Complex Systems Institute and co-author of a paper critiquing the Imperial College model.

US could see 2,300 virus deaths a day, even with social distancing, study says

Britain, despite belatedly implementing unprecedented lockdown measures that largely confined the population to their homes, has already recorded more than 17,000 deaths, with unofficial estimates putting the toll at more than twice that.

If the British government had implemented every possible measure quickly – including lockdowns, travel restrictions, mass testing and contact tracing – it could have brought the outbreak under control within weeks, Bar-Yam said, minimising both deaths and the massive economic and social fallout.

“The main problem is that people are not understanding that if you develop a very elaborate model, it confuses you with the details and that’s where policymakers got lost because they believe in specific predictions of the model instead of understanding what the general message has to be,” Bar-Yam said. “The general message has to be that the disease is terrible, that’s enough.”

Neil Ferguson, who led the modelling work at Imperial College, did not respond to a request for comment.

Models are limited by the questions they seek to answer in other ways, too. In particular, the simulations guiding governments did not take into account the economic and social costs of the harsh measures such as lockdowns that their projections implicitly or explicitly support – costs that an increasingly vocal minority of sceptics fear could prove worse than the disease itself.

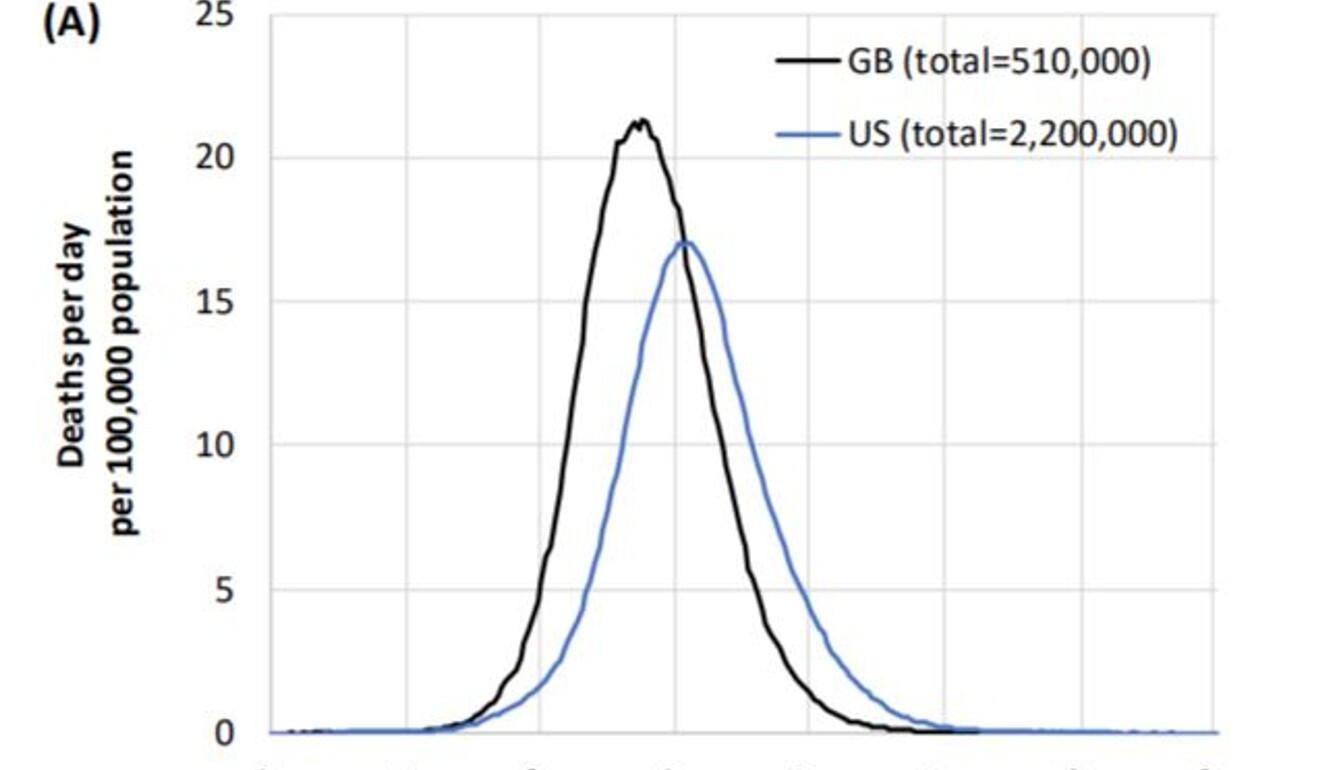

Bolstering these concerns, a paper published by scientists at Harvard and Peking universities this week concluded that efforts to “flatten the curve” by countries such as the US, Britain and Italy had done little to prevent new infections, while inflicting massive economic pain. The paper, which was not peer reviewed, described the strategy of trying to prevent a spike in infections through stay-at-home orders and the closing down of public venues and non-essential businesses as the “worst scenario in terms of cost-effectiveness”.

Modellers themselves have acknowledged such gaps in their projections and at times appeared keenly aware of the likely resistance to their most drastic suggestions, such as the finding by Harvard University researchers earlier this month that intermittent social distancing may be necessary into 2022.

The researchers, at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health, noted the “profoundly negative economic, social and educational consequences” of such measures and insisted they “do not take a position on the advisability of these scenarios given the economic burden”, while nevertheless predicting a “potentially catastrophic burden on the health care system” otherwise.

In theory, there is nothing to stop models also weighing economic and social factors, although doing so in practice would make already slow and complex calculations that much more complicated.

Sara Del Valle, a mathematical epidemiologist at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, said that while including “every single variable is challenging or maybe impossible due to lack of needed data, we can build models to consider multiple variables and trade-offs between those variables”.

“We tend to start with simpler models and build up as more information becomes available,” she said.

In principle, at least, the mathematics behind modelling are relatively straightforward and similar across simulations. Calculations are based on estimates of how many people are at risk of infection, how many people are infectious and how many people will die or have recovered and are therefore assumed to be immune.

More sophisticated models subdivide the population into groups by age, sex and employment and other variables to project which people come into contact with each other and where. The most advanced simulations give individuals specific rules for how to act on a particular day or in a certain situation.

Complicating the relatively simple underlying principles is the reality that even a slight change in a variable can produce a wildly different outcome – a problem that is even more acute in the early days of an outbreak when modellers must make do with incomplete data about factors like the mortality rate and average number of infections passed on by each sick person.

I think people make models because they can

“Their overshadowing problem is that they have to rely on a number of assumptions about figures we don’t have,” said Johan Giesecke, an epidemiologist who serves as an adviser to the World Health Organisation and the Swedish government.

Giesecke, who served as the first chief scientist of the European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, said the Imperial College model, for example, had greatly underestimated the proportion of asymptomatic coronavirus infections.

Policymakers had generally been much too reliant on models that tended to be “very good for teaching infectious disease epidemiology, not much else”, he said.

“I think people make models because they can. Computers are probably part of the reason.”

Giesecke said most people “would be surprised to learn how many physicists and mathematicians suddenly take up infectious disease modelling”.

“They are usually the ones who show least understanding of the problems with surveillance data, with the biological processes, and with human psychology,” he said.

The Imperial College team had previously predicted up to 250,000 deaths from mad cow disease, according to Giesecke, when the eventual number was fewer than 250.

Other experts argue that focusing on exact numbers misses the point.

Ruth Etzioni, an associate professor at the University of Washington’s School of Public Health, said the fact that the Imperial College model might not be precisely correct was much less important than the effect it had in getting sluggish authorities to act against the pandemic.

“Overreacting is not a word to use,” she said. “We didn’t have a choice because our governments weren’t prepared, and in the absence of that preparation the only way to try to tame this raging exponential process was to stop being in contact with each other.”

Etzioni said it was also a mistake to view the fact fewer people were dying than predicted as a flaw of the modelling – rather than a consequence of effective measures to slow the spread of the virus.

“I think that model did a great service and we should not … make the mistake of comparing what has happened since then, because the scenario that has played out is not something that they projected,” she said.

Expectations may be a problem. Modellers themselves stress that their creations are not “crystal balls”. Instead, they “provide evidence of what might happen or a range of possible outcomes given a set of assumptions and parameters,” said Elizabeth Hunter, an infectious disease modeller at Technological University Dublin. Viewed in that light, models can have real value, she said.

“There’s a lot of unknowns about Covid-19, and a lot of ideas about how to slow the spread and when to lift the restrictions,” Hunter said. “In lieu of testing and saying in this half of the population we’re going to close schools and restrict movements and in the other half let everyone go about as normal, modelling is really the only way to compare strategies right now.” ■