Explainer | Singapore’s 13th general election: what’s at stake in July 10 polls?

- The ruling PAP will be seeking a strong vote of confidence in its ‘4G’ leaders including PM Lee Hsien Loong’s designated successor, Deputy PM Heng Swee Keat

- Singapore’s coronavirus response and economic woes are among the issues that will feature in a relatively muted campaign with no mass rallies

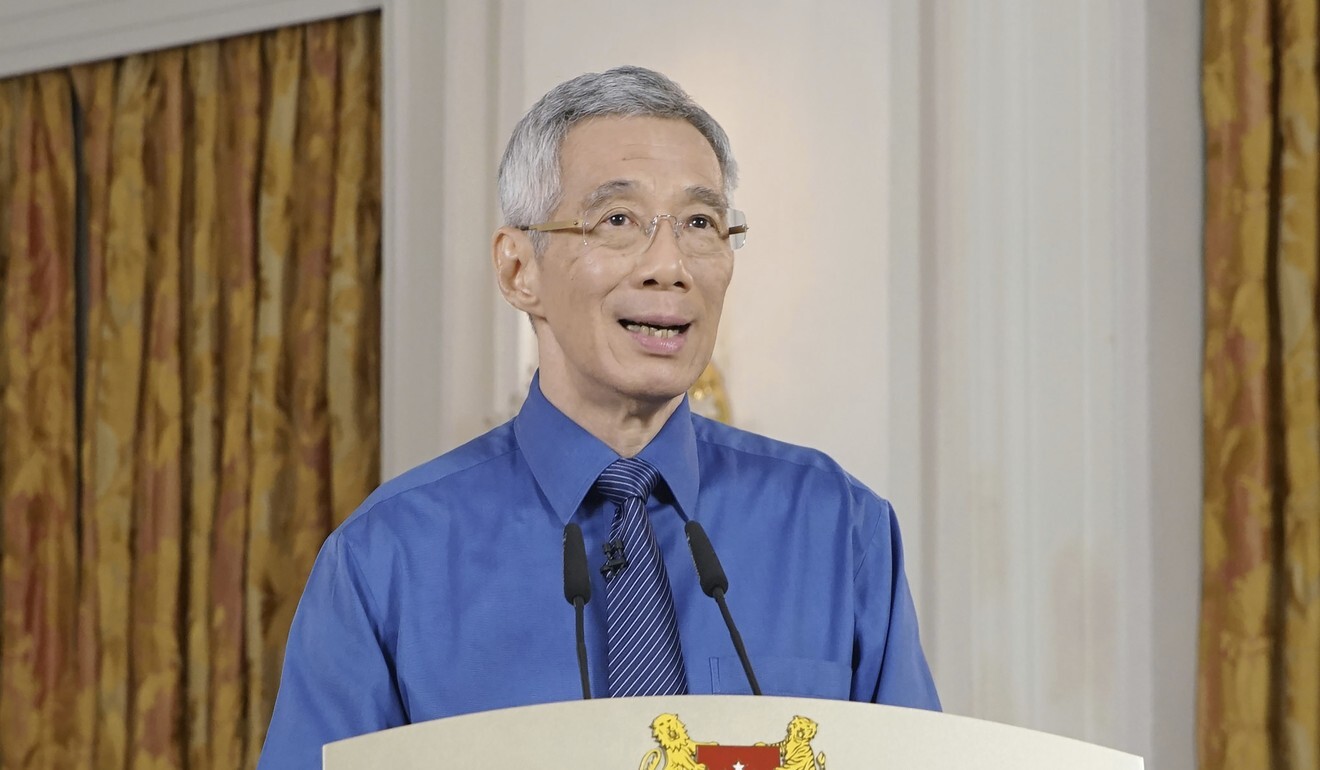

Singapore’s ruling party will be seeking a strong vote of confidence in its next generation of leaders when the country goes to the polls on July 10.

Singapore heads for July 10 general election

The ruling party will face off against 12 small opposition parties that are grappling with a range of internal problems and a political landscape favouring the incumbents. Some have openly said they do not seek to form the government.

The Workers’ Party – the only opposition group elected to Parliament in the 2015 polls with six seats – has in the past campaigned by urging voters to support alternative voices as a check on the PAP’s authority.

Last year, Lee Hsien Yang said he “wholeheartedly” supported the newly-formed PSP.

Here is what’s at stake in Singapore’s 13th general election:

CAMPAIGNING DURING THE PANDEMIC

All candidates must submit their nominations on June 30 for 14 single-seat wards and 17 group representative constituencies (GRC). The GRCs, which have four to five members, must have at least one non-Chinese candidate to ensure a multiracial mix in Parliament.

A walkover will be declared in constituencies that are not being contested by the opposition. For other constituencies, the nine-day campaign period will kick off and last until midnight on July 9.

All candidates must adhere to a “Cooling Off Day”, when no campaigning is allowed, on July 9.

Singapore election: no mass rallies but more media airtime for candidates

The elections department has urged parties to use digital platforms to reach voters. All parties will also have greater access to broadcast media than in prior elections.

Special arrangements for the July 10 poll include voters being allocated suggested time slots to minimise crowds at polling stations – although voting can be done anytime from 8am to 8pm – as well as 25 per cent more polling stations and priority voting for senior citizens on the morning of the election.

In previous elections, opposition rallies have attracted large crowds and enthusiastic expressions of support. There is usually less interest in the PAP’s rallies, although its lunchtime rallies in the central business district do attract thousands of white-collar workers.

LITMUS TEST FOR 4G LEADERS

Reuben Wong, an associate professor of political science at the National University of Singapore, said the election loomed as an opportunity for Heng and his 4G team to command a “strong endorsement” from voters.

“People will be seeking answers and some vision for the future, [such as if] the PAP has the best team to take Singapore into a volatile and uncertain world,” he said.

The 4G group includes 16 PAP leaders aged 43 to 59. Heng and other 4G ministers were last year appointed to key portfolios in a cabinet shake-up regarded as an important step in the PAP’s managed succession.

Some opposition parties have already indicated they may criticise the preparedness of the 4G team to take the reins from Lee and his lieutenants, such as senior ministers Teo Chee Hean and Tharman Shanmugaratnam.

In keeping with PAP tradition – and in a process that echoes the selection of a new pope – the 4G group in 2018 unanimously selected Heng as primus inter pares, or “first among equals”, after an internal contest.

Commentator Felix Tan noted the 4G team’s extensive exposure in recent years, saying they have been “in everyone’s face”. That was further heightened as a result of the coronavirus pandemic when Prime Minister Lee appointed 4G leaders such as National Development Minister Lawrence Wong, Manpower Minister Josephine Teo and Trade and Industry Minister Chan Chun Sing to the multi-ministerial task force overseeing the government’s response to the crisis.

WHAT ARE THE LIKELY CAMPAIGN ISSUES?

Analysts expect the government’s response to the pandemic to be vigorously debated during the campaign period. PAP ministers have defended their performance and pushed back against criticism about their handling of infections in foreign worker dormitories. Mass infections in these crowded residences account for the majority of Singapore’s cases, now more than 42,400.

Tan, an associate lecturer at private university SIM Global Education, said the PAP must also contend with criticism of “several rather draconian measures” the government implemented after cases began to rise in late March.

A partial lockdown known as the “circuit breaker” came into effect on April 7, and the measures are now being eased. The coronavirus recession and the labour market’s haemorrhaging are also likely to feature heavily during the campaign.

The government projects the trade-reliant economy to contract by between 7 and 4 per cent this financial year, putting it on course for its worst year since independence in 1965.

Lee’s administration has outlined an extensive plan to create jobs to replace those lost during the crisis and has pledged to restructure the economy to expedite post-pandemic recovery.

BATTLEGROUNDS AND BLACK SWANS

Despite electoral reforms such as an increase in single-seat constituencies in recent years, Singapore’s political landscape remains tilted in the PAP’s favour. And, given the tendency for voters to support the PAP in times of crisis, commentators expect the 12 opposition parties to struggle.

The ruling party benefits from deep links with influential quasi-governmental groups such as the People’s Association (PA), the trade union umbrella network NTUC, as well as the presence of active party branches in every ward. PAP leaders serve as “grass roots advisers” with access to vast PA resources even in opposition-held constituencies.

In contrast, opposition parties struggle to attract public support for activities outside election season, and many are bogged down by funding issues with no ready network of patrons.

Like the PAP, the Workers’ Party was founded in the 1950s and contested the most seats of any opposition group in recent elections. In 2011, the party won its first GRC. It was a breakthrough in Singaporean politics and raised hopes of sustained success but the party has since lost some of that momentum.

Former leader Low Thia Khiang, chairman Sylvia Lim and current party chief Pritam Singh were last year found liable for millions of dollars in a civil suit relating to the mismanagement of municipal funds. They have appealed the verdict.

Singapore election: the PAP’s order and stability will win out

The party will be hoping to retain the five-seat Aljunied GRC and the single-seat ward of Hougang. In 2015, confronting an upswing in public support for the PAP, the Workers’ Party won Aljunied with 50.96 per cent of the vote after a dramatic late-night recount, edging the PAP’s 49.05 per cent.

The five-seat East Coast GRC, which is held by the PAP, also looms as a key battleground where the Workers’ Party will hope to make gains.

Otherwise, observers are watching the newly formed Progress Singapore Party, led by former PAP stalwart Tan Cheng Bock. Tan, 80, plans to contest the West Coast GRC, which includes the single-seat ward where he was MP from 1980-2006.

Political observer Felix Tan expects Tan Cheng Bock’s party to dent the PAP’s vote share in constituencies where it fields candidates but does not expect the veteran politician to be elected.

Other opposition players include the Singapore Democratic Party and the Singapore People’s Party, both of which have previously won seats.

Sons, mothers, money and memory: theories about the Lee Kuan Yew family feud

Singapore’s changing demographics may also shape the results. Millennial and Gen Z Singaporeans now constitute a third of the electorate, with 933,000 citizens aged 20-39 as of 2019.

Tan said these younger voters could be a “black swan” factor, introducing an element of uncertainty due to their emphasis on social issues such as climate change, minority rights and the country’s wealth gap.

“The [PAP] needs to realise that these social issues are coming to the fore because these younger voters … are more educated, more globalised and more liberal in their thinking,” Tan said.