Advertisement

‘Chinese in India are terrified’: an SOS to Canada as border stand-off raises spectre of 1962 war

- During the last war between China and India, New Delhi interned thousands of Chinese-Indians in a POW camp, fearing they represented a ‘fifth column’

- Amid a new border dispute that has claimed dozens of lives, many fear they will be scapegoated once again – and are asking Justin Trudeau to help

Reading Time:8 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

On the first of July this year, 15 days after dozens of soldiers died in hand-to-hand combat between Indian and Chinese troops in the Galwan Valley of the Himalayas, a letter made its way to the Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Over three pages, it addressed the border dispute between the two Asian giants from a unique point of view, one that has gone largely unreported in the press: that of the Chinese-Indian community.

After greeting Trudeau, and praising his stance on social justice, the letter urged him to view this community’s plight through the prism of history.

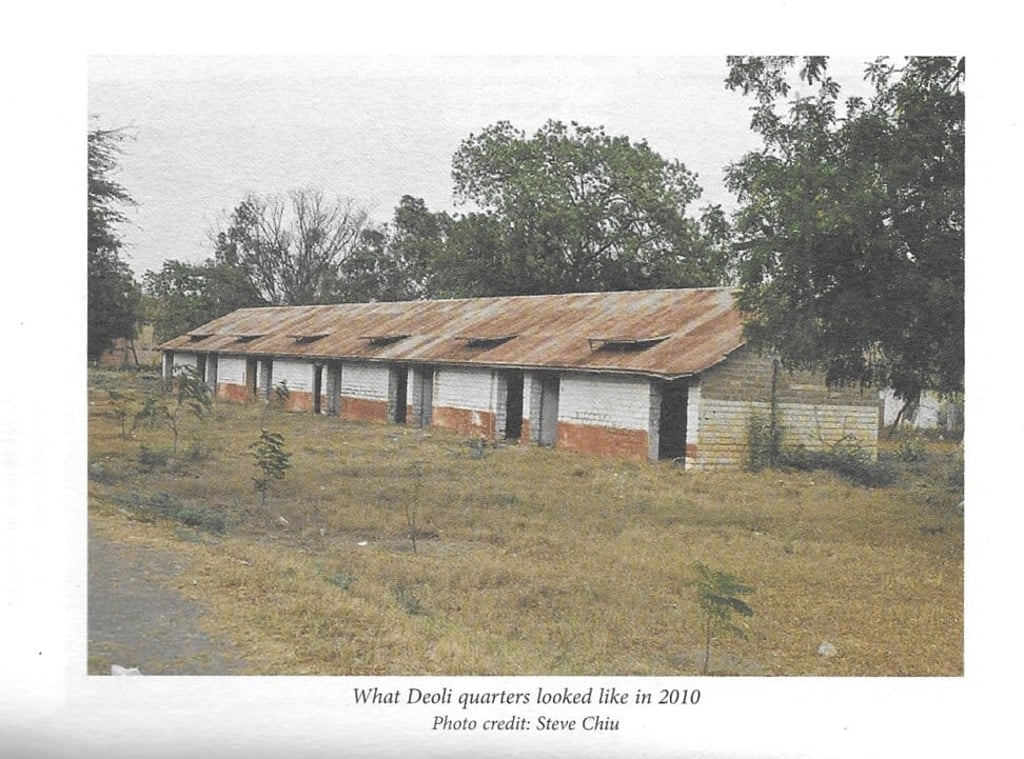

It reminded him of how during and after the 1962 war that India lost to China, thousands of Chinese-Indians had been interned in a POW camp left over from World War II in Deoli, a dusty town in Rajasthan.

Advertisement

New Delhi had been suspicious that this community of about 50,000, based mostly in what was then called Calcutta, could be a “fifth column” sympathetic to the Chinese cause. Among the 3,000 Chinese-Indians it interned were old men, women and children. Families were often separated; in cases where one spouse was ethnically Indian, the other Chinese, the Indian would be spared by the government. Properties were confiscated.

Advertisement

The letter pointed out that even after the war ended, the internments continued; it was not until 1967 that the last inmates were released.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x