Singapore-China relations, 30 years on: can the 4G leaders hold their own, and will the US rock the boat?

- On the anniversary of diplomatic ties, a new generation of politicians are looking to navigate challenges including the escalating US-China rivalry

- There are also questions over the changing bilateral power dynamic amid China’s rise, and the impact of ongoing disputes in the South China Sea

The next day, Singapore’s The Straits Times underscored just how important the event was for the island republic with the headline “China ties come after long period of gestation”.

According to the national daily’s account, the short ceremony saw China’s then foreign minister Qian Qichen and his Singaporean counterpart Wong Kan Seng sign a communique before making a “toast to our friendship”.

China, friend or foe to Singapore? How a wily Lee Kuan Yew made it both

In a recent interview, Wong said this was because of regional anxieties in Southeast Asia at the time. Given the island nation’s majority ethnic-Chinese population and its Muslim-majority neighbours, there were concerns racial affinity might be manipulated and the country might become a “third China”.

To keep these suspicions at bay, Singapore made a political decision to become the last Asean country to formalise ties with China, and it followed suit only after Indonesia re-established ties with China in August 1990.

It was not just the long wait that made the moment significant. East Asia’s smallest and largest countries by land mass were formalising ties at a time of dramatically shifting geopolitical tectonic plates; the Soviet Union was to fall a year later.

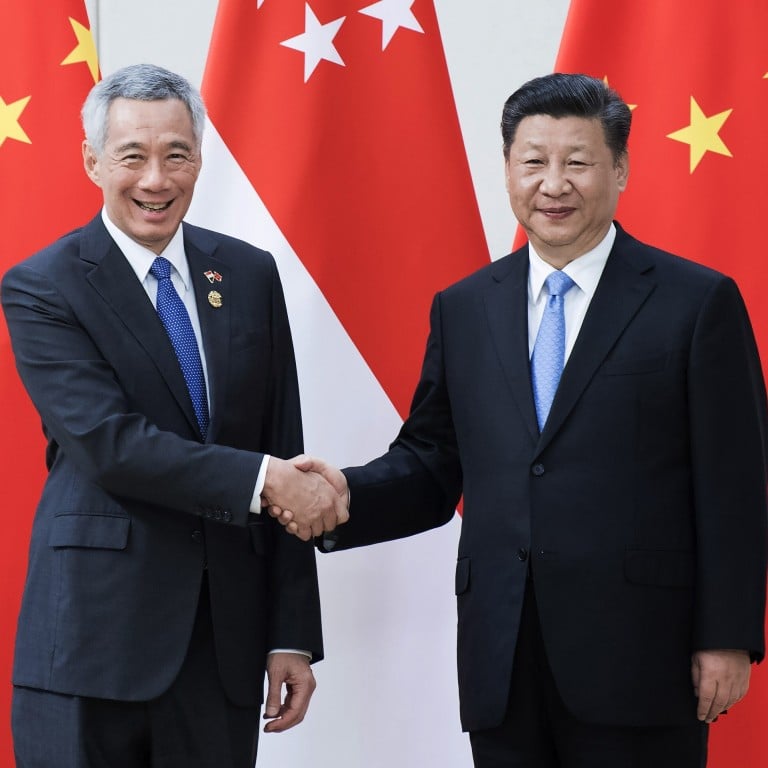

Despite occasional friction, China and Singapore still deem each other close friends, as evidenced by comments from both sides ahead of the 30th anniversary of their official ties.

Hong Xiaoyong, Beijing’s ambassador to Singapore, last month lauded the generational effort that had gone into forging the relationship.

“Today’s good China-Singapore ties did not just fall from the sky overnight. It is the product of small steps over decades,” he said.

Diplomatic observers who spoke to This Week in Asia about the bilateral relationship as it enters its fourth decade said there was no doubt both sides had gained since the modest signing ceremony in New York.

But at the same time, the commentators almost in unison agreed that political principals on either side would need to contend with considerable challenges to keep the relationship on an even keel.

Today’s good China-Singapore ties did not just fall from the sky overnight

For Singapore, analysts said the foremost question was whether the new generation of leaders who were poised to succeed the current prime minister – Lee Kuan Yew’s eldest child – would be able to hold their own in dealing with their counterparts in Beijing.

They added that China, which is caught up in an escalating geostrategic rivalry with the United States, would need to seek ways to engage Singapore without making the city state – reputed for its adroit diplomatic touch – feel that it was being asked to take sides between the superpowers.

LEE KUAN YEW’S WAY OR A NEW WAY?

Notwithstanding the impact Lee Kuan Yew had on his country’s ties with China, analysts said there were signs the younger, so-called 4G – or fourth generation – leaders of Singapore’s ruling People’s Action Party were coming into their own.

Lee – who visited China 33 times in a political career that spanned six decades – forged a strong kinship with former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, which observers said became a cornerstone of the bilateral relationship. Deng visited Singapore in November 1978 before China embarked on its reform and opening up scheme to transition to a market economy. He was impressed with its social discipline and order and, on returning to China, instructed his officials to look to the island nation for inspiration.

Lee named Deng as the greatest statesman he had ever met, and upon the Singaporean patriarch’s death in 2015, Chinese President Xi Jinping feted him as an “old friend of the Chinese people” – an accolade Beijing reserves for only a select few.

Irene Chan, an associate research fellow with the China Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, noted that leaders from the island nation after Lee had made strides in building a strong relationship with China, and were also committed to supporting Beijing’s paradigm shift from a centrally planned economy to a market economy “with Chinese characteristics”.

‘Three Lees is too much’: Goh Chok Tong on leading Singapore after Lee Kuan Yew

She cited how Goh Keng Swee was an economic adviser to the top Chinese leadership on tourism development and the opening of Chinese coastal cities in the late 1980s, following his stint as Singapore’s deputy prime minister from 1973 to 1984.

Subsequent governments, led by Goh Chok Tong and Lee Hsien Loong, did not deviate from that level of engagement with Beijing. “I would argue that there is no lack of enthusiasm from the 4G leaders to deepen engagement with Beijing and to carry on Lee Kuan Yew’s legacy as part of the ruling party’s political legitimacy,” she said.

But she noted that with China’s rise, it was “only natural” that Singapore’s leaders might find it harder to stand out in their engagement with Beijing compared with other countries, especially those that were recipients of Chinese funding for projects through the likes of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Sino-Singaporean ties, she said, were shaping up to be an institutionalised relationship cemented by layers of bilateral cooperation between governments with intertwining economic interests, adding that the new leaders “should be able to steward relations” without the old guard.

Dylan Loh, an assistant professor of public policy and global affairs at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University (NTU), said he believed the relationship had in recent years evolved into a “more comprehensive, broad-based one beyond solid personal ties between the countries’ leaders”.

“I do see a very strong desire to engage with China across all levels by our 4G leaders,” he said. “The tempo and intensity of diplomatic exchanges involving 4G leaders are quite apparent.”

I do see a very strong desire to engage with China across all levels by our 4G leaders

Indeed, government-to-government exchanges have continued even amid the Covid-19 pandemic, spearheaded by key 4G members such as deputy premier Heng, trade minister Chan Chun Sing and transport minister Ong Ye Kung. But even as these younger leaders engage with their Chinese counterparts with the same tenacity as Prime Minister Lee, his predecessor Goh Chok Tong and current senior minister Teo Chee Hean, some observers believe personality-driven diplomacy could have a limited impact in the future.

Do Singapore’s 4G leaders know their people well enough?

Lynette Ong, who researches Southeast Asia as an associate professor of political science at the University of Toronto, pointed out that there was much more “economic complementarity” between the two nations during Lee Kuan Yew’s 1959-1990 stint as prime minister – a time Beijing was “not powerful enough to pose a threat politically”.

Chong Ja Ian, a political scientist and scholar of Chinese foreign policy at the National University of Singapore, said conditions had changed in the bilateral relationship, with China now wielding far more leverage on account of its economic might.

“In this regard, the thrust should be how Singapore can have a stable and more institutionalised relationship with China that is based on international law and self-restraint rather than what ties particular leaders have,” he said. “Basing an important relationship largely on personalistic ties may actually be unnecessarily risky. After all, individuals tend to come and go.”

The US could also be a factor, according to Chinese scholar Pang Zhongying, who said he believed that as Beijing looked to turn inward as a result of souring ties with Washington, its relations with Singapore would retreat to a lower level.

“The relationship between China and Singapore is entering its new stage, which may be quite different from the previous one,” said Pang, an international relations academic at Ocean University of China. “It will be filled with uncertainties in many aspects.”

DOES CHINA STILL NEED SINGAPORE?

In 1992, when Deng embarked on his famous tour of southern Chinese cities to revive support for reform and opening up, he said China must learn from Singapore’s development and stable society. Chen Nahui, an assistant professor at the China University of Political Science and Law, wrote in a piece for the ThinkChina website last year that Deng’s comments sparked “Singapore fever” – a process of using the Singapore model to modernise China.

Deng, she said, was not just aiming to revitalise the stagnant reform process but wanted to uphold “Singapore’s authoritarian rule, using its social order and stability to justify his own crackdown in Tiananmen Square, which served to strengthen the Chinese state’s single-party rule”.

Singapore soon became the top overseas training ground for Beijing, with more than 50,000 Chinese officials and cadres having attended study trips and training programmes in the city state since the mid-1990s. But a dip in enrolment numbers in recent years has led to speculation about whether China still needed to learn from Singapore.

Analysts said there had been a shift in what China wanted from the republic: there was once a hunger to learn about economic policies and urban planning, but Beijing’s interests had since diversified to include finance, banking and tourism.

Similarly, despite China’s transformation, Loh from NTU said Singapore was still inherently appealing to China, given factors such as its majority ethnic-Chinese population and how it was “not exactly a liberal democracy by Western standards”.

“Beyond that, I think the Chinese see value in having a reputable and trusted friend – that does not have the image problems that many of its closest friends have – to stand on its side,” he said, adding that Singapore had been prepared to speak up for China at various stages of its emergence.

Can Singapore maintain its sweet spot between China and the US?

“Although our candidness may sometimes grate on their sensibilities, I think Beijing appreciates that honesty and that neutrality.”

Chung Ting Fai – managing partner of boutique law firm Chung Ting Fai & Co, which handles local and cross-border disputes – argued that there were also tangible benefits Singapore could offer China, despite its eroding edge.

The city state had been attracting a steady stream of Chinese firms looking to settle disputes, he said, adding that mainland China’s arbitration centres were “quite weak” in legal expertise and were not on a par with international players such as Hong Kong and Singapore.

These disputes, he said, often arose between either two Chinese parties or a Chinese firm and a foreign entity, and stemmed from projects under the belt and road plan. Chung said he was also conducting classes for Chinese lawyers who were keen to practise arbitration.

02:35

Belt and Road Initiative explained

Nicholas Poon, a Singapore-based dispute lawyer, said Singapore’s status as a neutral venue for arbitration was viewed favourably when it came to matters involving Chinese companies and China-related issues.

“Rightly or wrongly, the Chinese legal system is perceived to be less sophisticated, savvy, and potentially susceptible to political influence,” he said. “With Singapore, Chinese companies can assuage foreign counterparts that their disputes, if any, would be resolved efficiently, fairly, and more importantly in accordance with the rule of law.”

Chinese firms could also use Singapore’s position to “neutralise the trust deficit they face in the Western world”, Poon said, calling the city state the “Switzerland of the East”.

In recent weeks, reports have emerged of Chinese tech giants making a move to Singapore amid closer scrutiny from Washington.

Can Beijing leverage overseas Chinese in struggle with US?

Tencent Holdings last month confirmed plans for a new Singapore office as part of its Southeast Asian expansion, and e-commerce giant Alibaba Group, which owns the South China Morning Post, is reportedly in talks for a US$3 billion investment in Singapore-headquartered ride-hailing company Grab. Content platform company ByteDance, the developer of the popular TikTok app, is also planning to invest “several billion dollars” in a data centre in Singapore, according to reports.

This could put Singapore in a tough spot, given the potential for it to be seen as a hotbed for Chinese firms looking to skirt American sanctions, analysts said, but Ong from the University of Toronto stressed that this trend of Chinese capital inflows was inevitable.

“The challenge is how to keep up with the rule of law so that the integrity of fundamental institutions is not compromised as a result,” she said.

Apart from that, Lee Yi Shyan, chairman of non-profit networking group Business China, felt Singapore was one of the ideal platforms for China to marshal resources for belt and road projects in Southeast Asia as the island nation was a regional transport, financial and business hub.

“Singapore can be one of the key platform cities from which international enterprises, including many coming from China, [can] address the infrastructural needs of Southeast Asia and beyond,” he said, though he added that like any other smaller economy it would need to develop new capabilities to attract a rising China.

THE U.S. FACTOR

Beyond China and Singapore’s utility to each other, analysts who spoke to This Week in Asia also stressed that factors outside the scope of the bilateral relationship could heavily affect its trajectory.

Foremost in their thoughts, naturally, was the impact the US-China rivalry was likely to have on ties between Beijing and the island nation.

The University of Toronto’s Ong suggested the rivalry would continue even if Democratic nominee Joe Biden triumphed over President Donald Trump in the November presidential election.

“Singapore will have to continue playing the balancing game, which it is adroit at, better than other countries that are still catching up with the geopolitical reality of the end of a unipolar world,” she said.

Singapore’s deputy prime minister Heng referred to this in his Lianhe Zaobao interview, in which he urged Washington and Beijing to establish mechanisms to mediate disputes amid their competition for influence. A failed US-China relationship, he said, would stifle the ability of countries to react to international issues.

Loh from NTU said Singapore’s balancing act in US-China ties was challenging but not a new issue, and many countries in Southeast Asia would also find it harder to navigate their ties with Beijing in the future.

Singapore will have to continue playing the balancing game

“It is somewhat trite to say that Singapore doesn’t want to choose sides. Nevertheless, I think a wide range of international political action will increasingly be politicised and seen through that lens,” he said, adding that any country’s economic, diplomatic and military decisions could be seen as taking a position.

The South China Sea dispute is viewed as one of the issues that has the potential to rock the diplomatic relationship. Singapore-China ties hit a trough in late 2016 and early 2017 after the city state refused to back China over the issue.

Instead, following a 2016 decision in The Hague’s Permanent Court of Arbitration in favour of the Philippines, which ruled that there was no basis for China’s so-called nine-dash line through which it claimed most of the waterway, Prime Minister Lee voiced support for international arbitration as a way to deal with such territorial disputes.

02:32

Washington’s hardened position on Beijing’s claims in South China Sea heightens US-China tensions

Singaporean diplomats, meanwhile, came under intense pressure during multilateral meetings for their stance in support of international law, with Stanley Loh – the city state’s then envoy to Beijing – and the Chinese nationalist mouthpiece Global Times at one point engaging in a war of words over the matter.

Both sides later set aside their differences, and Lee visited Beijing in September 2017.

The episode not only caused a strain in bilateral ties, but also triggered a sharp debate within Singapore’s foreign-policy elite.

Kishore Mahbubani, a former top Singapore diplomat, was publicly admonished by the country’s foreign-policy establishment after he penned an op-ed suggesting the friction could have been avoided if the government had exercised discretion in discussing “matters involving great powers”.

In Singapore, a search for a Chinese identity with a little less China

NTU’s Loh said the incident showed that while Singapore had always taken a consistent position on respecting international law, in this issue, China felt it was supporting the Philippines and the US.

He added that what was noteworthy was that both countries were able to quickly move on from the incident.

Still, Chong from the National University of Singapore felt the island nation needed to have serious internal discussions about contingencies and the risks involved should the US-China friction intensify.

“Obviously, everyone hopes that the US and China can resolve their differences quickly and amicably, but there is no guarantee of that type of eventuality,” he said. “Should that be the world Singapore has to face going forward, it should be preparing for it – not just within the administration and public service, but among the population as well.”

Despite the challenges, Loh felt that Singapore could still navigate changing Sino-Singaporean dynamics, even though he noted that smaller states would typically have less agency in which to operate.

“In areas where we do differ, we are able to contain and manage it so that no lasting damage is done. I don’t see the road ahead as necessarily riskier but it will certainly be less clear.” ■