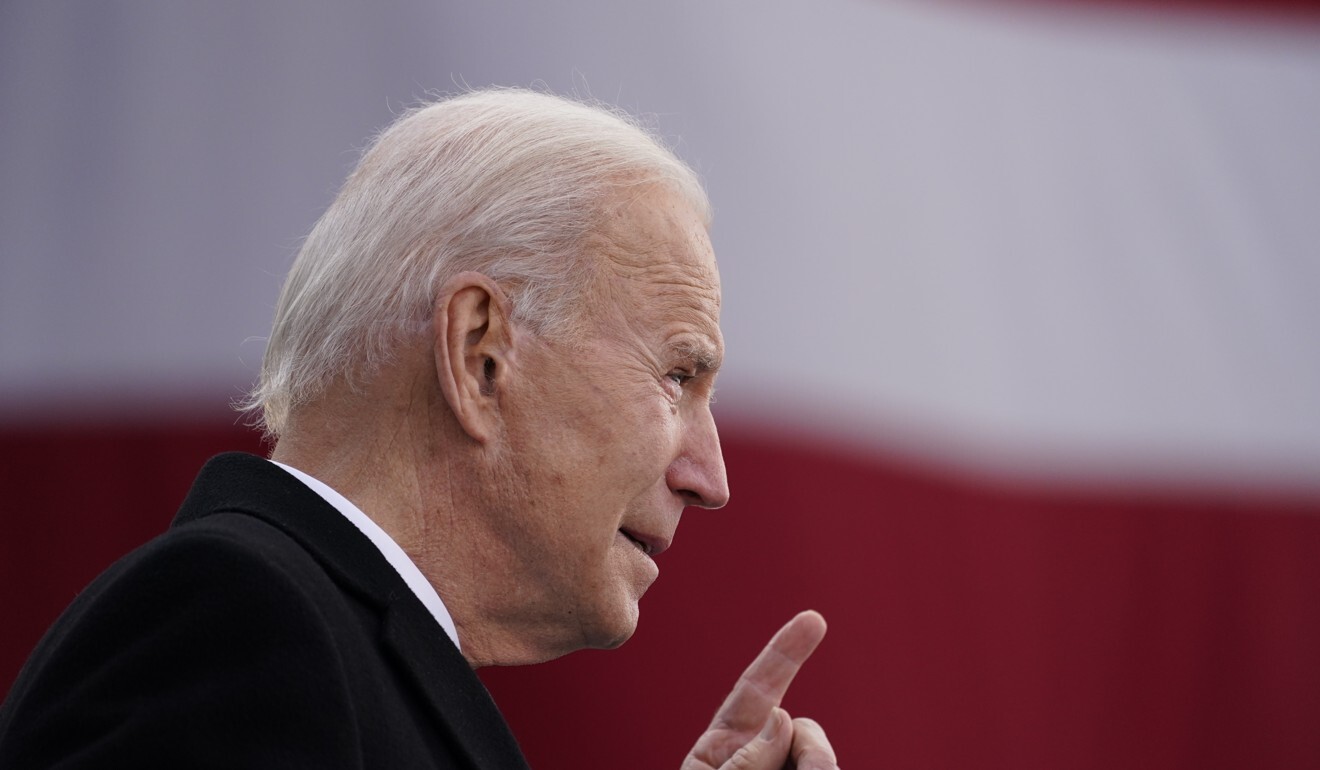

When President Biden gets tough on China, can US count on Vietnam?

- New leaderships give Washington and Hanoi a chance to boost ties, but Vietnam will be keen not to anger communist stablemate China

- To win Hanoi’s trust, the US may need to tone down its human rights criticisms and take a tough line in the South China Sea

While the growing US-China rivalry will elevate Vietnam’s importance to Washington, it will also make Hanoi wary of angering Beijing, they say.

Booming Vietnam beat Covid-19, but can it face up to China?

The US and Vietnam normalised bilateral relations in 1995, two decades after the end of the Vietnam war. In 2013, under the presidency of Barack Obama (when Biden was vice-president), the former adversaries signed the US Vietnam Comprehensive Partnership, which is aimed at strengthening ties in a multitude of areas from politics, trade and defence to health, the environment, humanitarian assistance and legacy of war issues.

HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUE

Even so, Thayer said Hanoi’s lack of complete trust in the US would be a problem for elevating ties further.

“Vietnam does not want to be ensnared in an anti-China relationship with the US and at the same time be criticised and pressured over its human rights record,” said Thayer.

With Biden having signalled that human rights will be one of the key concerns of his presidency, Vietnam’s patchy record in this area may be problematic.

Indeed, it could be a “hurdle for elevating the ‘comprehensive partnership’ to a ‘strategic partnership’,” said international relations lecturer Huynh Tam Sang, from the University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vietnam National University-Ho Chi Minh City.

Why did China’s foreign minister omit Vietnam from his Southeast Asia tour?

On Wednesday, Amnesty International called on Vietnam to end what it said was an assault on human rights defenders and individuals exercising their rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly.

However, Yamini Mishra, Amnesty’s Asia-Pacific regional director, said the new leadership that emerged from the Congress would “provide an invaluable opportunity” for the country to “change course on human rights”.

If the US can put its concerns over human rights to the side, it may have much to gain.

Lye Liang Fook, a senior fellow and coordinator of the Vietnam Studies Programme at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, said given the uncertainties surrounding US-China relations, Vietnam’s relative importance to the US had increased.

“The US considers Vietnam as a key partner in its overall strategy of responding to what it perceives as an assertive China,” said Lye, adding that this could be seen in the visits within a month of both US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien late last year.

Bill Hayton, an associate fellow with the Asia-Pacific Programme at Chatham House, an international affairs think tank based in London, said Biden was likely to engage Vietnam as a regional partner and with less tension than had characterised relations under Trump.

Vietnam dodged the coronavirus bullet, so why are its workers struggling?

Still, Hayton, the author of Vietnam: Rising Dragon, said there would always be a limit to US-Vietnam engagement as Hanoi saw Washington as a threat to its political model, particularly in “spreading political pluralism and peaceful evolution”.

SOUTH CHINA SEA TEST

Huynh said one of the most important signals Vietnam would be watching for was Washington’s response to “China’s threat in Southeast Asia in general, and the South China Sea in particular”.

“Biden promised that the US does need to get tough with China. His vow will be tested soon,” said Huynh.

02:32

Washington’s hardened position on Beijing’s claims in South China Sea heightens US-China tensions

In recent days, China has taken a somewhat aloof approach in its dealings with Vietnam. Foreign Minister Wang Yi did not include Vietnam as a stop on his recent tour of the region.

Some analysts saw this as a snub and a sign of growing antagonism and tensions between the old Communist allies over the Spratlys – a disputed island chain in the South China Sea. This antagonism had been compounded by uncertainties over Hanoi’s internal power politics, they said.

Peng Nian, deputy director and associate fellow of the Research Centre for Maritime Silk Road, National Institute for South China Sea Studies in China, said the South China Sea situation would only become more challenging after the Vietnamese Congress as the new leadership would need to be tough on the issue to consolidate power.

Given Biden’s likely enthusiasm for strengthening ties with Hanoi, Peng said Vietnam was likely to emerge as “an important partner” in Washington’s Indo-Pacific strategy, which is aimed at curbing Chinese influence.

EXPLAINED: How Vietnam will pick new leaders amid rising China, US tensions

“So naturally, defence cooperation between Vietnam and the US will be strengthened, and this will arouse China’s suspicion. So China-Vietnam ties are also likely to fluctuate,” Peng said.

He added that it was possible Hanoi would interfere with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ discussion on the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea, thereby widening its rift with Beijing.

“Before the Code of Conduct is signed, Southeast Asian countries might undertake unilateral efforts in developing resources in the region, thereby heightening tensions there,” he added.