Advantage China, as democracy slides from view in Southeast Asia

- Strongmen in power in Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia, single parties in Laos and Vietnam, and democracy eroding in Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia

- If Southeast Asia is in an ‘authoritarian race to the bottom’, analysts say it will play into the hands of one of the countries in the US-China rivalry. Guess which one?

01:34

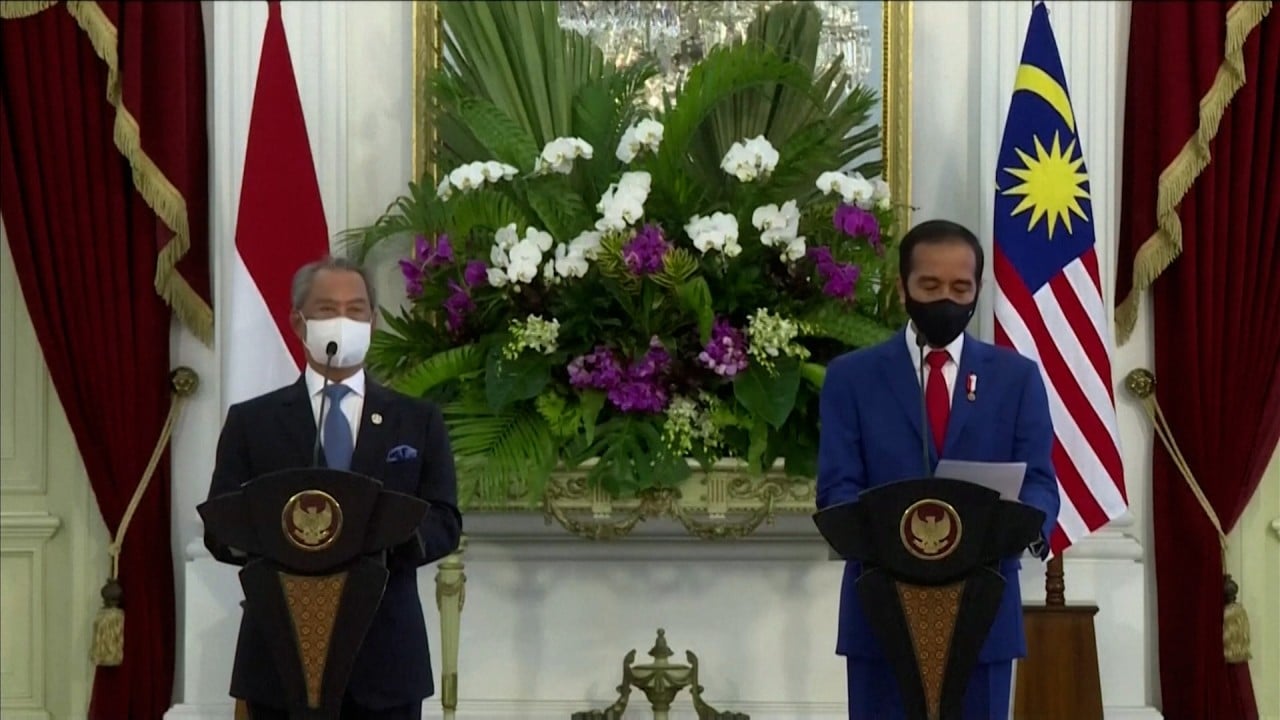

Indonesian and Malaysian leaders urge Myanmar to resolve political differences through legal means

That feeling is borne out in hard data. The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) democracy index released last week showed little progress had been made in the sprawling region of over 600 million people. Some areas had even gone backwards.

In a commentary this week, the respected Thai political science professor Thitinan Pongsudhirak characterised the 10-nation neighbourhood as a “banana region”.

Other countries too “either have no popular elections or face erosion of democratic rights and values,” he wrote. “The only democratic stand-out, by virtue of not backsliding, is Singapore.”

His party failed to win a legislative majority but has a hold on power due to support from military appointees in the senate.

“The authoritarian resurgence in Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia will further tarnish Asean’s reputation as a club of strongmen and regimes that are devoid of popular legitimacy,” Thitinan told This Week in Asia, referring to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

01:16

Myanmar junta leaders hold first meeting of military government the day after staging coup

Waqas Adenwala, Asia analyst with the EIU, said the “decline of democracy in the region will have far-reaching geostrategic implications”.

‘No one on our side’: from Thailand to Singapore, Myanmar nationals react to coup

BALANCING ACT IN JEOPARDY

Than Shwe, the so-called ‘old man’ of the Tatmadaw who led the junta from 1992 until 2011, cultivated China when Myanmar was hit by extensive sanctions from the West because of its military rule. His successor Thein Sein’s accession coincided with a thawing of ties with the West as the military elite began realising the downsides of relying too heavily on its northern neighbour.

Suu Kyi, one-time political prisoner of the Tatmadaw and leader of the National League of Democracy (NLD) that won landslide polls in 2015 and again last November – much to Min Aung Hlaing’s displeasure – had in contrast adopted a more balanced foreign policy outlook.

At the same time, the 75-year-old kept ties with China on an even keel, well aware that the relationship with Myanmar’s biggest trading partner could not be taken for granted. Beijing has in recent years invested billions of dollars in Myanmar, with a China-Myanmar Economic Corridor – part of the Belt and Road Initiative – currently in the works to connect Kunming in Yunnan, China, to the Kyaukpyu special economic zone on Myanmar’s western coast.

That in turn, could jeopardise efforts by neighbours who have assiduously worked to balance the influence of Washington and Beijing instead of taking sides.

Chong Ja Ian of the National University of Singapore said democratic backsliding and authoritarian consolidation were “real causes for concern” in the region especially at a time of heightened major power friction.

Authoritarian regimes’ tendencies – including their lack of transparency and restraints on power – meant there would be “more conducive conditions for elite capture by external entities and resort to the use of force”, said the political scientist.

Chong raised the example of the Cold War, where “external competition” was incentivised through local proxies in various countries, including in Southeast Asia.

Myanmar coup set to test US role as defender of democracy, say analysts

In the context of the current great power competition, Thitinan said it was Beijing that was most likely to gain from Southeast Asia’s democratic backsliding.

The 15-nation Security Council on Thursday issued a statement calling for the release of Suu Kyi and scores of NLD leaders arrested on Monday, but stopped short of condemning the putsch.

00:28

China hopes Myanmar resolves differences under legal framework after Aung San Suu Kyi detained

‘BETTER TO ENGAGE’

Other regional analysts suggested it may be too early to make presumptions about the Tatmadaw’s foreign policy stance – and urged all outside powers to keep an open mind about engaging the military leaders.

One of the loudest calls among Myanmar watchers in the West has been for governments to resist talking to Min Aung Hlaing. Echoing those calls have been activists within Myanmar. Speaking in a webinar on Thursday, activist May Sabai Phyu said it was important for the international community to avoid contact with the “illegitimate government”.

“Do not provide any financial or technical support to them, [but instead] support civil society organisations [that are] organising a lot of non-violent campaigns and activities to restore civilian rule and strengthen democracy,” said the director of the Yangon-based Gender Equality Network.

But Kavi Chongkittavorn, a veteran commentator on Asean affairs, said the situation required “creative diplomatic approaches” as “conventional black and white approaches would not work”.

“With the ongoing competition among great powers, any power that comes down hard on the country that has different norms and values would have to think twice,” Kavi said. “External pressures are essential to a point to effect internal changes. But many authoritarian leaders are resilient and flexible enough to counter outside pressure.”

In such a scenario, the regular Bangkok Post columnist said “engagements have a better chance of influencing changes, especially when they are from the neighbouring countries”.

Liew Chin Tong, the former Malaysian deputy defence minister whose alliance was thrown out of power by a political coup last year, said he too was not fatalistic about the region’s democratic slide – despite being among those on the receiving end.

04:08

'Worst nightmare': violence feared after Myanmar military coup

The battle for power among its political elite has been multidimensional, with plotting continuing unabated through the pandemic.

Despite such setbacks, Liew said Southeast Asian democrats should be optimistic given that the voting public had tasted the benefits of democracy as well as its disappointments.

Myanmar aerobics instructor dances to Indonesian protest anthem as coup unfolds

In Malaysia, Thailand and now Myanmar it was the younger generations who, having experienced democratic rule, were now at the vanguard of resisting autocracy, using unconventional methods to mobilise dissent.

“And they are not going to forget these experiences. You can’t compare it to the 1990s. It will be much harder for authoritarian regimes to be resilient and sustain themselves,” Liew said.