Anti-Asian hate: in South Korea, reports of attacks on Asian-Americans focus on suspects’ race – a lot

- Unlike in the US, South Korean media put heavy emphasis on the race of attackers, many of whom were African-American

- The stark contrast in framing highlights differing sensitivities around race that permeate the two cultures, analysts say

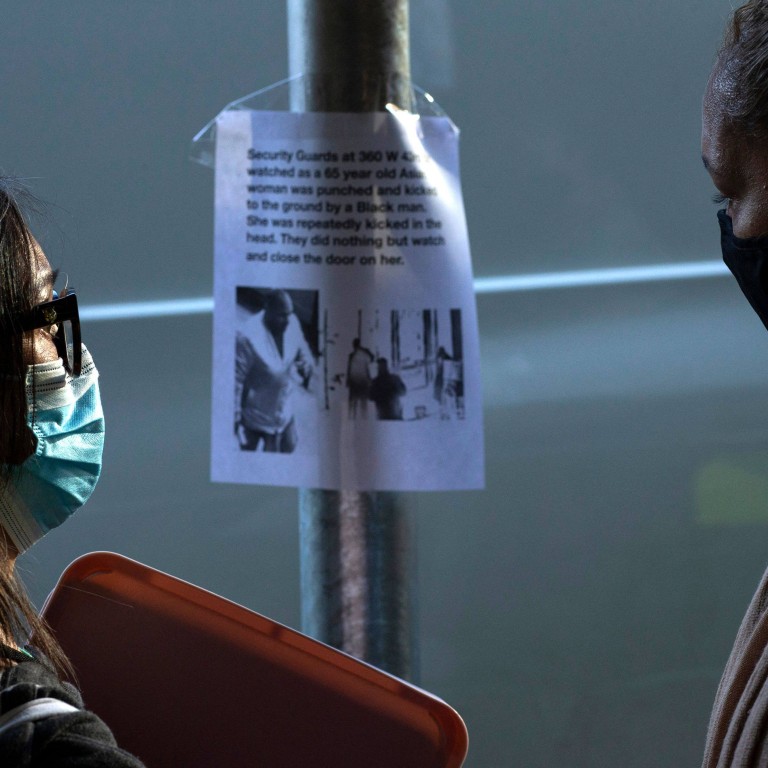

When news broke of the latest violent attack against an Asian-American in New York City on Monday, it ricocheted across the South Korean mediasphere, generating countless articles and news bulletins.

Filipino-Americans on high alert after New York attack

On Thursday, an article about Brandon Elliot – the suspect in Monday’s attack – ranked as the most-read piece on the website of Korean broadcaster JTBC.

While US news reports did not highlight the race of alleged assailants in many recent attacks, South Korean media outlets have readily identified suspects by race in articles and even headlines.

In one article, the state-funded Yonhap News Agency mentioned Elliot’s race and that of another man who was reported to have attacked an Asian man on the New York subway on Monday no fewer than 26 times. Both Elliot and the suspect in the subway incident – which a witness later said appeared to have actually involved a Hispanic man who used a racial slur – are Black.

South Korean media have highlighted the race of suspects in numerous other attacks being investigated as hate crimes, including an incident last month in which a group of African-American women were filmed assaulting a Korean-American beauty store owner in Houston, Texas.

As their ‘American dream’ sours, Koreans in the US eye a return home

“Race holds different meanings and different power in different countries – it is just more sensitive and less tolerant to point out one’s race in the US due to its long and contentious history of racism,” said Gi-Wook Shin, a Korean-American sociology professor at Stanford University.

For Koreans, ethnicity is so integral to identity that “it seems just a natural thing for Korean media to mention race along with other socio-demographic characteristics,” Shin said.

“I do not think that mentioning race itself reflects certain prejudice Koreans hold toward certain minorities, but I do agree that such information can strengthen the already existing prejudice against certain minority groups – such as African-Americans or Hispanics.”

Michael Hurt, a visual sociologist of African-American and Korean descent who lives in Seoul, said South Korean society had a history of associating African-Americans with violent crime as a result of the tensions exposed between the black and Korean-American communities during the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

“Koreans want to know the real deal. Is it safe? And safe in America definitely brings up Black faces in the Korean mind,” Hurt said.

“Do Black people inherently hate Asian people? I don’t think that’s true, I don’t think that’s ever been true, but I think there’s a perception of that as true in Korea, and how the media has to speak to that is a pretty tricky thing.”

Koreans now have exactly the same racism as in the West, which views African-Americans – and Africans – to be inferior to whites

US media reports have largely avoided mentioning the race of the alleged assailants in recent attacks involving other ethnic minorities, although some outlets made passing reference to Elliot’s race after he was charged.

Elaine Kim, an ethnic studies professor at UC Berkeley, said US media had overemphasised the race of criminal suspects in the past, when White Americans were considered “simply human”.

“Reporting it was swinging in the wrong direction,” Kim said. “Not reporting it is staying in place.”

Korean media lacks sensitivity in dealing with race, said Park Kyung-tae, a sociology professor at Sungkonghoe University in Seoul, who blamed the influence of Western attitudes.

“Koreans now have exactly the same racism as in the West, which views African-Americans – and Africans – to be inferior to whites,” Park said.

Vietnamese-Americans examine feelings for land that saved their parents from war

Many Asian community leaders and activists have said they believe Long, who claimed to have been motivated by a “sex addiction”, was driven by anti-Asian sentiment, although authorities have said they have yet to find evidence to support hate crime charges.

Shin said that while individual perpetrators should be punished regardless of their race, it was also important to “reflect on the causes of these minority-minority conflicts”.

“One could argue that white supremacy has not only divided whites and non-whites but also weakened solidarity among different minority groups,” he said.

The intense focus on Long’s race and motivations has led some commentators in the US to accuse the media and activists of employing double standards to push a simplistic and politically correct narrative about insurgent white supremacy, despite the reality of violence cutting across racial lines.

Although difficult to quantify, hate crimes against Asians rose nearly 150 per cent in 2020, according to an analysis of police statistics from 16 US cities by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism. In New York alone, police have received 33 reports of anti-Asian hate crimes so far this year, compared to 28 for all of 2020. Neither set of figures break down offenders by race.

In the US Department of Justice Crime Victimization Survey for 2018, Asian-Americans were found to be the only community that was more likely to be victimised by a member of another racial group than their own.

According to those statistics – which cover all violent crime and not hate crimes specifically – 27.5 per cent of offenders against Asian victims were black, followed by whites and Asians, at 24.1 per cent each, and 7 per cent were Hispanic.

Black Lives Matter: for Koreans, a reminder that racial discrimination is legal

Joseph Yi, an associate professor of political science at Hanyang University in Seoul, said there was a generational divide between first-generation immigrants who had experienced violence first-hand from other minorities and younger, college-educated Asian-Americans who “mainly think in terms of white supremacy”.

“Violence is violence, harassment is harassment,” said Yi, who grew up in Los Angeles. “It shouldn’t matter where it comes from. A lot of people, because they have these ideological blinders, they don’t see that.”

He said much of the commentary about the issue had been “intellectually lazy” and driven by ideology, adding: “If you just look at crime data in general, you are most likely to be victimised by members of your own group.”

Hurt said he did not believe that US media outlets were guilty of hypocrisy in being sensitive in covering the race of perpetrators, but acknowledged the possibility of “overcorrection” in some cases.

“If it’s just straightforward white supremacy, white people acting out, that just makes more sense, but I think when you see other people of colour beating up other people of colour you kind of scratch your head and think I don’t really understand what’s going on,” he said.