Singapore’s press overhaul will stay true to Lee Kuan Yew’s 50-year-old blueprint

- Singapore Press Holdings will hive off its media outlets into a non-profit entity, allowing it to seek funding from diverse sources

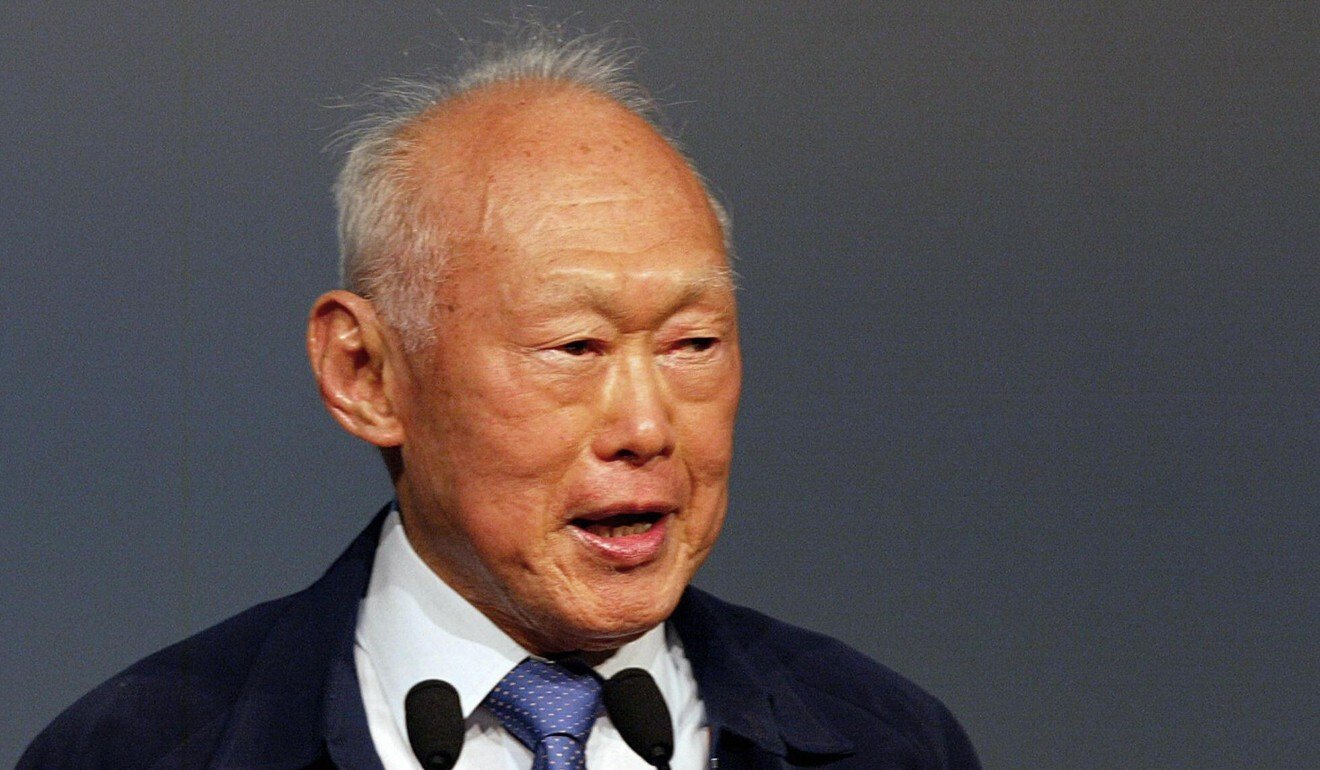

- But to assess this move, it’s worth recalling Lee Kuan Yew’s 1971 clampdown that has since shaped the role played by the media

It is a fitting coincidence that the biggest shake-up of Singapore’s news media industry in decades has been announced in the 50th anniversary month of the country’s biggest ever crackdown on press freedom.

Justifying the sweep to an international gathering of editors in Helsinki the following month (he seemed to relish the opportunity), Lee declared that in Singapore “freedom of the press, freedom of the news media, must be subordinated to the overriding needs of the integrity of Singapore, and to the primacy of purpose of an elected government”.

This has remained the position of the PAP government ever since. It demands the media not interfere with – and mostly support – its broad, voter-approved national agenda.

Three years later, in 1974, the government installed an ingenious new regulatory framework for the press, in the form of the Newspaper and Printing Presses Act (NPPA). This system worked with, rather than against, media owners’ profit motives. Lee realised that to eliminate headstrong publishers like the family owners of Nanyang Siang Pau, there was no need to embark on communist-style nationalisation.

Freedom of the press, freedom of the news media, must be subordinated to the overriding needs of the integrity of Singapore

In a neoliberal move that predated the worldwide neoliberal revolution, the NPPA went the opposite direction – entrusting newspapers to the stock market. To stop any shareholder from securing a controlling interest against the government’s wishes, the NPPA placed a cap on holdings, which currently stands at 12 per cent.

The NPPA also requires newspaper companies to allocate super-voting status to some shareholders on the government’s orders. Almost half of SPH management shares are held by non-state financial institutions such as OCBC and UOB. State-linked entities such as Singtel and DBS Bank account for slightly more than half.

Whether they are part of the government’s vast Temasek family, what these management shareholders have in common is a strong preference for preserving political stability over experiments in democratic accountability.

Singapore PM Lee Hsien Loong says economic outlook brighter amid global recovery

The system allows the government to vet key appointments and set editorial directions of newspaper companies. Ordinary shares, meanwhile, gave other institutional and retail investors a stake in SPH profits – which was bound to grow along with a booming economy and advertising market, even if journalists were not free to speak truth to power.

Lee was probably the first authoritarian leader to understand that shareholders’ greed could be used to counter citizens’ democratic longings.

The strategy worked for about 40 years, while newspapering was an immensely profitable business. Patrick Daniel, former editor-in-chief of The Straits Times group, noted that in the good old days, SPH aimed for 30 per cent margins on average. The Straits Times, the company’s cash cow, enjoyed far higher profit rates.

“Those days are gone – savaged by the technology platforms which have sucked up the bulk of advertising revenues,” he said.

Writing last July, Daniel was the first to hint at what was to come: “I’m convinced that newspapers have to find a new ownership model to survive – either be owned by a billionaire or convert to a public trust. I much prefer the latter, and predict ST will go that way …”

In the coming months, SPH will transfer all its media assets to a wholly-owned not-for-profit subsidiary, SPH Media. SPH owns all of the country’s dailies. The move would make Singapore the only advanced industrial country in the non-communist world with no major profit-driven news organisation.

What are ‘Asian values’ and is the concept still relevant today?

SPH chairman Lee Boon Yang explained that it was no longer viable for its media outlets to remain “part of a publicly listed company where it is subject to expectations from shareholders of profitability and regular dividends”.

This is a point that journalists around the world would appreciate instantly. Corporate media are renowned for prizing shareholders’ interests over journalists’ professional responsibility to serve their publics. In many cases, editorial capacity has been shrunk not because companies are making losses, but because they are not profitable enough.

In response, many new media ventures have gone the non-profit route. In Asia, these high-quality news outlets include The Wire in India, The Reporter in Taiwan and Citizen News in Hong Kong. Their founders know the commercial marketplace does not necessarily serve the marketplace of ideas. This is an insight that predates the digital disruption – it is as old as Karl Marx’s critique of capitalism.

Chinese social media set abuzz as Singapore PM-designate steps aside

It is also the basis of the entire tradition of independent public service broadcasters, such as the BBC; and the rationale behind media operated by trusts and foundations. SPH cited two examples: The Guardian in the UK, controlled by the Scott Trust, and Florida’s Tampa Bay Times, owned by the Poynter Institute.

SPH said its new structure would enable it to seek funding “from a range of public and private sources with a shared interest in supporting quality journalism and credible information”. The state and its network of companies will no doubt respond favourably when SPH passes the hat around, with the government already saying on Thursday it was ready to offer the new entity funding support.

In theory, public funding can coexist with fiercely independent, public interest journalism. In addition to the likes of the BBC, there’s the Scandinavian model of state subsidies for newspapers, to support media diversity. They are set up to ensure public funds are linked to public accountability – but not political quid pro quos.

Singapore media spin-off into non-profit entity sparks questions over future of journalism

If SPH and the Singapore government are serious about quality journalism, they can learn from these overseas examples how to institutionalise editorial independence.

That is unlikely to happen, which is a shame, because the global digital disruption is only one reason SPH is in trouble. The other – the elephant in the room – is the government’s stranglehold on Singaporean journalism. The state demands that journalists equate the government’s interests with the public interest, preventing media from developing a strong relationship with their audience.

Therefore, SPH’s suggestion that its proposed media vehicle follows precedents like The Guardian is misleading. Remember May 1971. The same political party is in charge, with the same fundamental media philosophy.

After decades of having a say in top newsroom and managerial appointments even when SPH was highly profitable, and routinely micromanaging editorial content even when they were not paying for it, it is hard to picture ministers suddenly discovering the value of editorial independence after the state becomes a major patron of the press. SPH’s next chapter was written 50 years ago.

Cherian George is professor of media studies and an associate dean at the Hong Kong Baptist University School of Communication.