As the West leaves a void in Myanmar, China ignores its own advice to invest

- While China’s official guidelines have previously cautioned against investing in conflict zones, the temptations in Myanmar are strong. Indeed, under the junta, joint development projects appear to be accelerating

- Some analysts say it is a dangerous strategy, as instability endangers billions of dollars. Others say the potential rewards – including rare earth minerals and access to the Indian Ocean – outweigh the risks

The personnel changes were made to the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor Joint Committee – which oversees a 1,700km infrastructure development plan that will connect Kunming, the capital of Yunnan in southwest China, with Myanmar’s major economic hubs – and the committee overseeing the Myanmar-China Cross Border Economic Cooperation Zones, to be built in Shan and Kachin states.

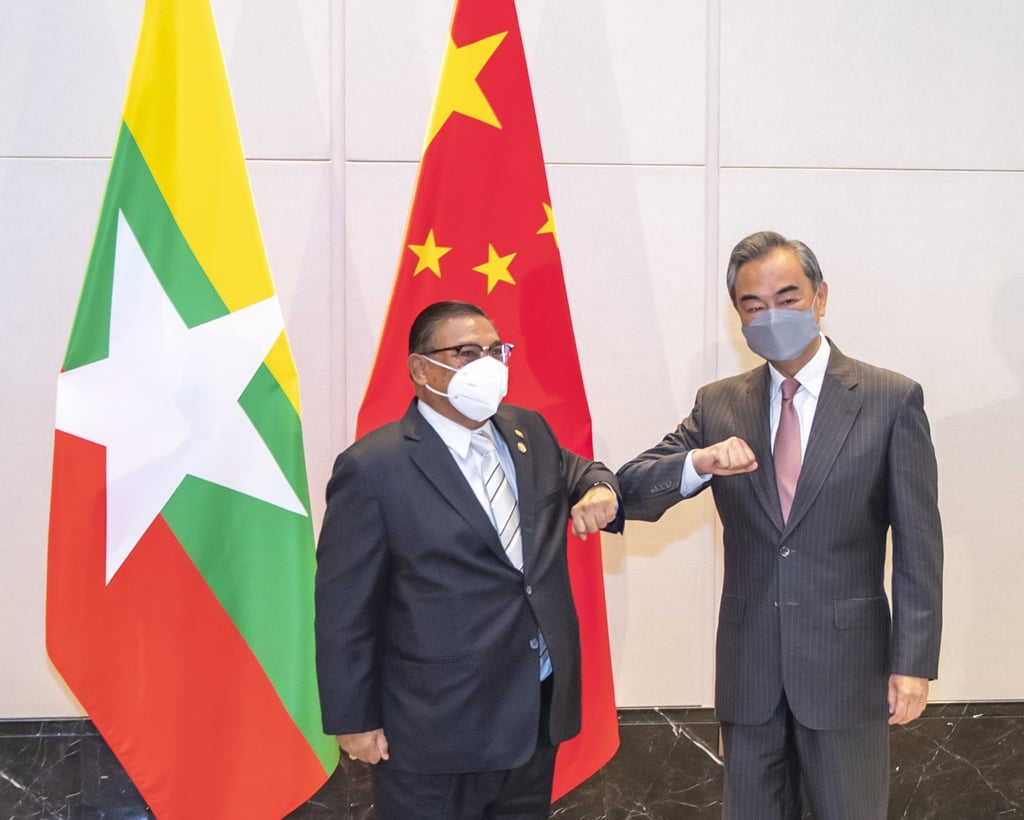

China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi then asserted during a meeting with his counterpart Wunna Maung Lwin in the Chinese city of Chongqing that Beijing “has supported, is supporting and will support Myanmar in choosing a development path that suits its own circumstances”.

“Beijing currently views the junta as likely to hold onto power, and it therefore hopes to leverage its pragmatic support of the Tatmadaw to advance its stalled projects,” Myers said.