Advertisement

China not Southeast Asia’s top investor, but fears over its economic influence persist: study

- Chinese infrastructure projects have drawn criticism in recent years due to the slow pace of delivery and the risk of landing countries heavily into debt

- But Japan, the EU and the US are ahead of China, while Southeast Asian states have meanwhile also been trying to diversify their economies amid the US-China rivalry

Reading Time:5 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

8

A study by researchers in Australia has found inconclusive evidence that China has undue economic influence over Southeast Asian countries, because it is not the region’s dominant investor despite widespread perceptions that it is.

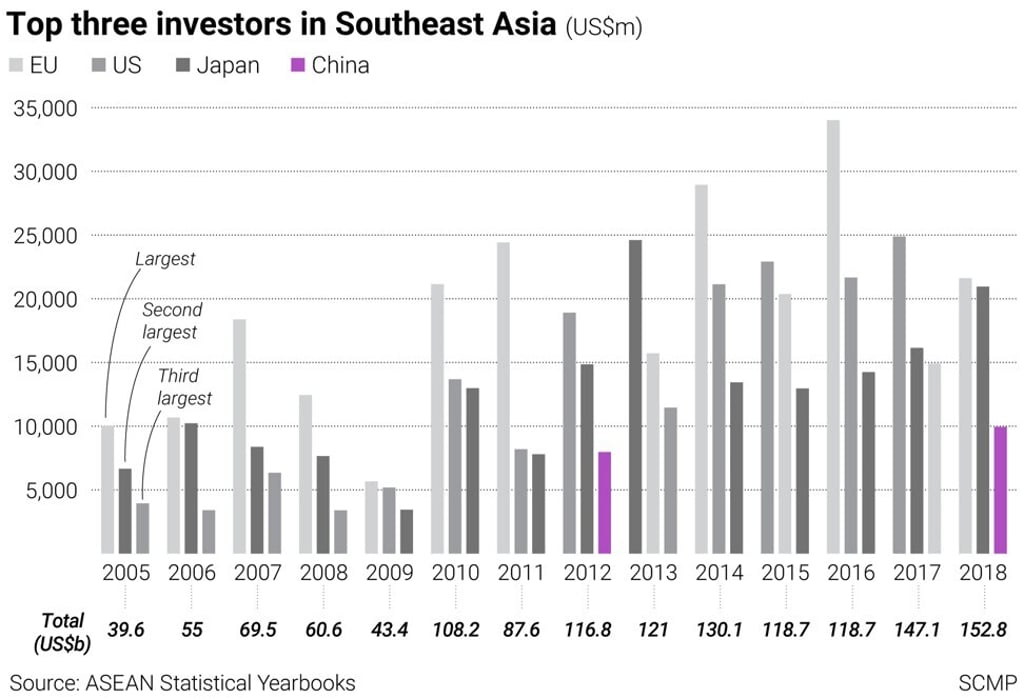

The EU bloc, Japan and the US have remained Southeast Asia’s three largest investors over much of the past two decades, according to the report published by the Australia National University (ANU), titled Chinese Investment in Southeast Asia from 2005 to 2019.

Between 2005 and 2018, the EU ranked as Southeast Asia’s top investor in 10 of those years, with the US taking the top spot thrice and Japan once, said research authors Evelyn Goh and Nan Liu from the university’s Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs.

Advertisement

China made it into the top third just twice over that period. In 2012, Chinese investments stood at US$7.9 billion, behind Japan’s US$14.8 billion and the United States’ US$18.9 billion. In 2018, Beijing invested US$9.9 billion, less than Japan’s US$20.9 billion and the EU’s US$21.6 billion.

Advertisement

Observers say the discrepancy between perception and reality is due to the high visibility and intense global scrutiny of Chinese infrastructure projects, especially those under the Belt and Road Initiative, amid the US-China trade rivalry.

Japan has consistently been the region’s largest infrastructure investor, with reports in the past few years noting that China was far behind.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x