Are cosier China-Cambodia ties a sign Beijing’s plan to set up military bases overseas is gathering steam?

- Experts say China has a strategic interest in having more such bases worldwide, not just to project military power but also to safeguard its global interests

- But while Beijing may be exploring this route in response to US-led efforts to counter its influence, the path to a network of outposts abroad is hardly straightforward

“Steel-like.” That was the expression China’s Ministry of National Defence spokesperson Wu Qian used last month, for the first time, to describe the friendship between Beijing and Phnom Penh, according to a report in nationalistic Chinese tabloid The Global Times.

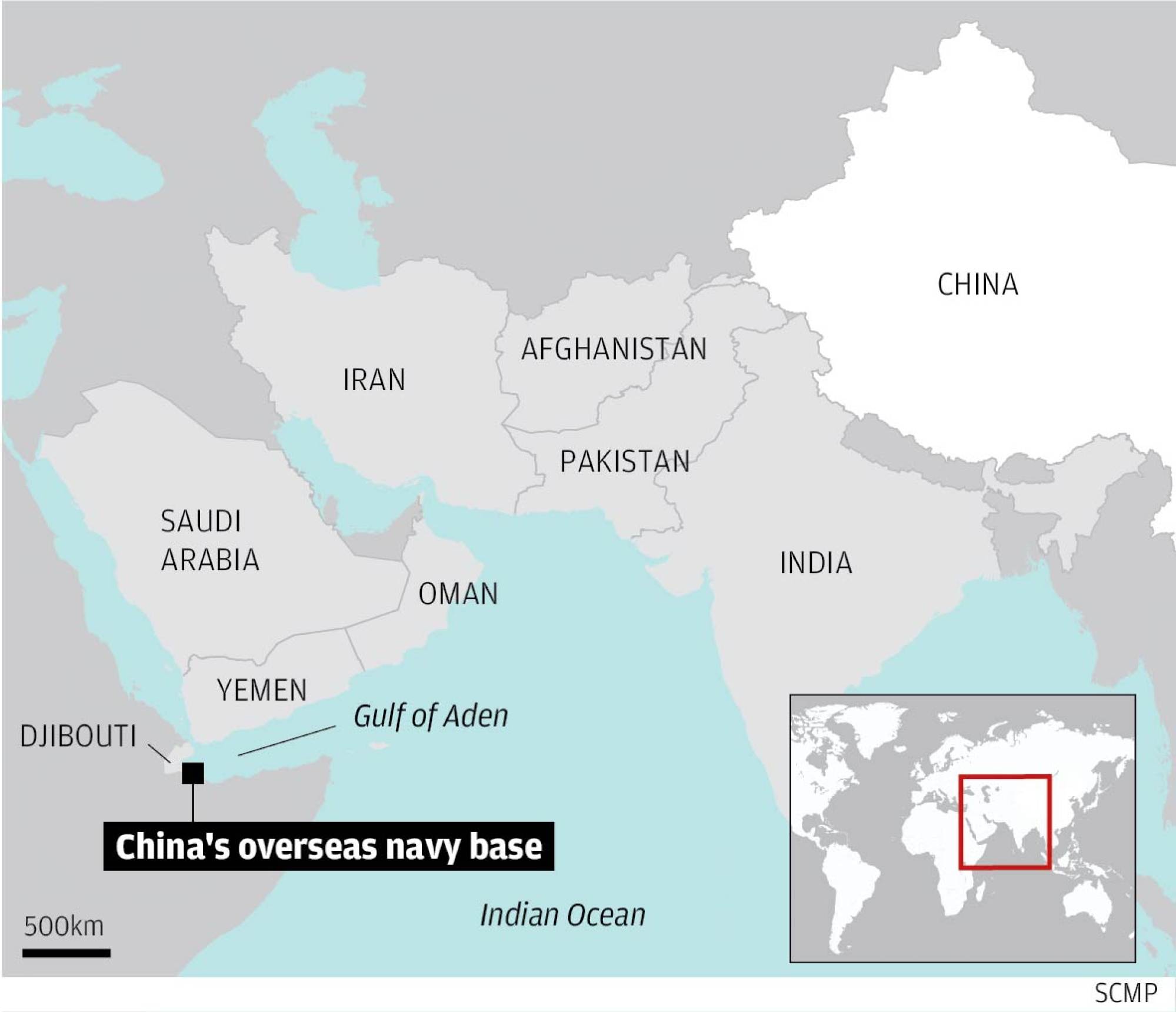

As it has only one overseas military base, in the African nation of Djibouti, analysts said China had a strategic interest in having more such outposts worldwide, not just to project military power but also to safeguard its global interests.

However, other experts argue that China may have turned to exploring foreign military bases given efforts by Western countries to counter Beijing, adding that its strategic goals have not kept pace with its growing economic might.

Ian Storey, a senior fellow with the Singapore-based ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, said given the rapid expansion of China’s global interests over the past decade, Beijing saw the need to establish a network of military access points around the world to protect and advance those interests.

“The ability to project power around the globe is a key consideration,” he said.

“[This will] both break this tightening encirclement and protect and defend China’s national interests along the Belt and Road Initiative-related countries and regions,” Jia said, referring to China’s ambitious global infrastructure and connectivity plan.

Malcolm Davis, a senior analyst in defence strategy and capability from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), said Chinese naval and maritime expansions should be seen within the broader context of rising Sino-American strategic tensions and competition.

China was seeking to challenge US strategic primacy in the Indo-Pacific and asserting its own interests as it promoted a revised rules-based order, while Washington was seeking to prevent Beijing’s domination of the region, he said. “This competition is occurring across all dimensions, and will be long-lasting,” Davis added.

Cambodia’s Ream Naval Base upgrade sparks worries of China link

Where else beyond Djibouti?

Set up in 2017 as a base for anti-piracy operations and responses to accidents at sea, the Djibouti facility sits near the strategically important Bab-el-Mandeb Strait linking the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea.

In an article published in Foreign Policy last month, Craig Singleton, an adjunct China fellow at the Washington-based think tank Foundation for Defense of Democracies, said Beijing was eyeing new military bases across the region.

According to him, countries on China’s wish list include Cambodia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Tanzania, and Kiribati, with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) having made “serious headway” securing new bases in the first three locations.

“Whether or not Washington can derail Beijing’s plans is anyone’s guess. Either way, US policymakers and military brass could soon wake up to a changed world, where the PLA can project its power far beyond the tense Taiwan Strait,” Singleton wrote.

James Char, an associate research fellow with the China Programme at Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, said there had been talk since 2015 that China was looking to set up military bases across the Indian Ocean in the direction of the Atlantic, with Namibia being a potential site.

In an interview with the Associated Press earlier this year, General Stephen Townsend, commander of the US Africa Command, said China had been approaching countries ranging from Mauritania to Namibia with the intention of setting up a naval facility.

If realised, the prospect would allow China to base warships from its expanding navy in both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

ASPI’s Davis said China also had access to the Gwadar and Hambantota ports located in Pakistan and Sri Lanka respectively, adding that Beijing was putting in place a network of future bases that could facilitate the PLA Navy’s long-range expeditionary operations.

“It’s entirely possible that additional bases might emerge in the South Pacific but also in Southeast Asia,” Davis said, noting that Australia would be extremely concerned about a growing Chinese presence in Papua New Guinea, East Timor and island states in the Southwest Pacific.

“Australia would work hard through diplomacy to prevent a Chinese naval or maritime security presence in these areas,” Davis said.

Cambodian officials accuse US of interference after Ream Naval Base visit

Southeast Asia? Only Cambodia

Storey from ISEAS said there was a less compelling strategic rationale for China to establish more military facilities in Southeast Asia as Beijing had already built seven large military bases on artificial islands in the Spratlys that allowed it to project naval and air power across the region.

Among the 10 Asean members, Storey said Cambodia was the most likely to accede to China’s request to increase its naval presence in the country, but he added that Phnom Penh was unlikely to agree to a permanent Chinese presence as this would completely undermine relations with its other close ally, Vietnam.

Cambodia and neighbouring Vietnam are former communist allies, and both countries share a defence relationship that they tend to characterise as being a pillar in their wider diplomatic ties.

‘Logistics and peacekeeping’

However, Jia at Chapman University said since the US Department of Defence issued its annual report on Chinese military power last September, there had been a year-long publicity campaign on China’s “alleged plan to build a global network of naval and military bases”.

The efforts – including Singleton’s Foreign Policy article – were part of ongoing efforts to secure a higher defence budget allocation from Congress, Jia said, adding that raising the prospect of a China threat also allowed America’s military-industrial complex to reap more profits.

As China calls, is writing on wall for US-Cambodia military ties?

Even though China was not in a hurry to build the bases, he said that the recent bus blast near the Dasu hydropower project – a vital part of China’s belt and road plan in Pakistan – that killed 13 people, including nine Chinese nationals, would have heightened Beijing’s urgency in expediting the bases’ construction.

“[This is] to ensure China’s security in countries and regions similar to Pakistan and Southeast Asia,” Jia said, adding that if built, such bases would not be military in nature like the ones built by the US, but would mainly be for logistics and peacekeeping purposes.

Pointing out that Beijing understood the unwanted international attention that came with a forward-deployed strategic presence, Char from RSIS said in view of the high strategic costs and prohibitive expenditure required, the PLA was unlikely to emulate American global military operations.

“In the near to medium term, China’s ambition on setting up overseas military bases is likely limited to the realm of non-traditional security and soft power building,” he said. “Getting a single base up and running already takes up many years, so if China does establish a network, that will surely be a far longer-term project.”

Dual-role facilities

In a Lowy Institute report published last Monday, China was said to be engaging in a massive campaign to build air and maritime facilities spanning the region, mostly under the belt and road banner.

“Ostensibly an effort focused on economic development, many of its resulting projects fall in highly strategically useful places, and are often of an uneconomic nature,” wrote Thomas Shugart, pointing to the huge port facility and airfield built at Hambantota in Sri Lanka, or the “underutilised but still expanding port facility” at Gwadar in Pakistan.

ASPI’s Davis said that by first establishing commercial access to ports and airports via the belt and road strategy, Beijing would then be able to ensure future naval access into the Indian Ocean and the Southwest Pacific.

Adding that China was using the belt and road plan as a means to expand its commercial, economic and political influence, particularly in fragile and developing states, he said Beijing was picking the locations “judiciously to ensure they are close to geostrategically important locations, which contribute to China’s defence and strategic interests”.

“So, although the language associated with the [belt and road plan] is often emphasising ‘win win’, its main purpose is to further China’s interests – the ‘win’ is for Beijing,” he said. “We see the BRI as a form of creeping imperialism, and we are seeking to challenge this strategy.”

Is new US-led Quad aimed at countering China’s influence in South Asia?

Pointing out that the concern over dual-role facilities was legitimate, Timothy Heath, a senior security expert at the Rand Corporation, a California-based think tank, said China did not seek, nor was it likely to obtain, the type of major military bases the US had in countries such as Japan.

American military forces are dispersed among 85 facilities covering more than 31,000 hectares on the Japanese islands of Honshu, Kyushu, and Okinawa, according to the US Department of Defence.

Heath noted that while major American military bases involved the permanent stationing of large numbers of combat forces that could sustain major combat operations over a longer time frame, China had no alliances and did not yet have the ability to carry out combat operations abroad for a sustained period of time.

“For Beijing’s purposes, it may be sufficient to have dual-use facilities that permit PLA ships and aircraft to resupply and briefly rest while carrying out missions primarily aimed against non-traditional threats along the belt and road routes,” Heath said.

While acknowledging the dual-role potential of some of the facilities, Char from RSIS said if the PLA wanted to gain access to them, Beijing would first need to reach a formal accord with the host countries, which would be “a drawn-out process”.

Given the negative perception of the Chinese military among many countries, Char said the question was an important one that Beijing would have to address, as failure to allay those concerns would lead “to the miscarriage of China’s grand strategy”.

Challenge to the US and Australia?

Even though the US already has a sizeable network of military bases around the world – close to 800 military bases in over 70 countries and territories, according to author David Vine – Washington is keeping a watchful eye on China’s next steps in setting up military outposts.

Storey from ISEAS said Chinese attempts at setting up such bases would be perceived by Washington as an attempt to challenge American hegemony.

Heath of the Rand Corporation said Washington was likely to be worried that a PLA presence in other parts of the world could result in the Chinese military cooperating and supporting adversaries of the US and its allies.

“For example, if China should gain [access to a base] in Iran, Beijing may offer more military assistance, intelligence support, or other forms of military aid to Tehran as the price for the access,” Heath said, pointing out that the result could be an Iran that was better prepared and even emboldened to use military force against a US ally or against American forces.

Davis from ASPI added that Chinese bases were likely to give the PLA forward access from which it could then project military power against the US and its allies, both in wartime and in peacetime as part of grey-zone operations.

Such operations have been described as a form of carefully scripted brinkmanship that tries to achieve objectives through carefully designed operations and cautious moves so as to avoid war, rather than seeking quick, decisive results.

For example, China’s plan to set up a fishing facility at Daru Island in Papua New Guinea involved establishing port facilities, which could in turn support Chinese fishing vessels and potentially Chinese coastguard vessels, Davis said.

“Given China’s coastguard law, the concern must be that from this facility – very close to Australian territory – there would be a risk of maritime security incidents and intrusions into our territorial waters,” he said, referring to the law enacted by China in February that allows its coastguard to fire on foreign vessels without prior warning.

“Such a development might occur below a level that would justify a military response, but would facilitate China’s ability to increase coercive pressure on Australia via grey zone operations,” Davis said, adding that this would represent a dangerous and immediate geographical challenge to Australia’s security interests.